Are Africa’s needs overlooked in energy transitions research?

African countries face a dual challenge of building broad-based prosperity for their citizens while responding to the global imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. While climate change and development objectives are increasingly being discussed in tandem in some policy circles, academic research has typically considered them separately. As the interconnections between energy, development, and climate become more apparent, it is important to ensure that the research that informs policy conversations reflects these interconnections.

In a recent study, we conducted a systematic review of 156 peer-reviewed energy transitions literature published between 2000 and 2021 to better understand the dynamics that are currently shaping energy transition dialogues in Africa. Here are the six main findings we uncovered:

1. Energy transitions research in Africa is a new but fast-growing knowledge space

The body of knowledge on energy transitions research in Africa is growing quickly, but it is largely a new phenomenon. Over 90% of the research in this space was published after the 2015 Paris Agreement, and 60% was published between 2018 and 2021 (See Figure 1). This suggests that African countries could have entered the Agreement with a limited knowledge base to inform their standing and the first nationally determined contributions (NDCs) commitments. However, the steady and steep growth in the number of papers published on Africa since the Paris Agreement can contribute to better and more informed climate and energy policy decisions, and NDC revisions.

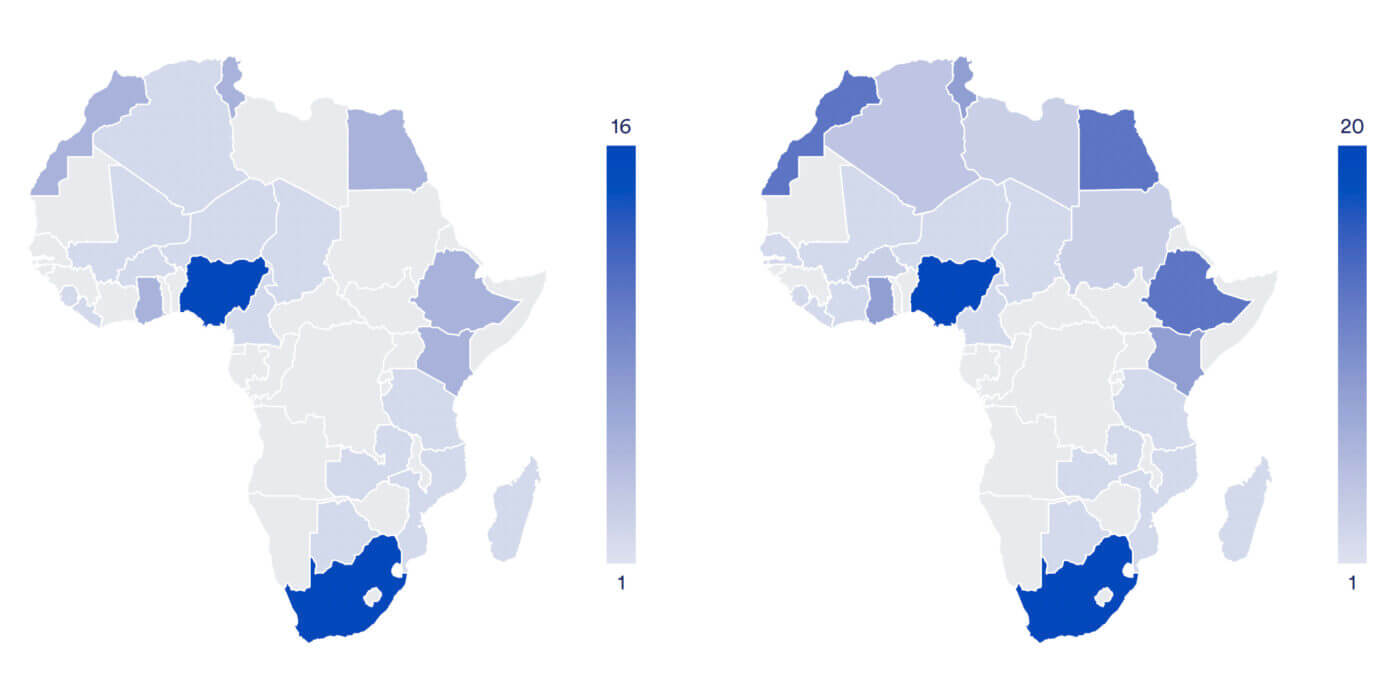

2. Energy transitions research in Africa is currently focused on a limited sub-set of countries

In terms of spatial coverage, over one-third of the studies focus on Nigeria and South Africa, the two largest economies on the continent (See Figures 2a-2b). Nearly half of African countries are not covered by current research. Given the contextual differences between African countries, this country-specific knowledge gap could limit the effectiveness of policy recommendations when applied broadly to all African countries.

3. The energy transition is a complex phenomenon but tends to be overly simplified

Most energy transition research papers explore scenarios using time horizons linked to common global targets (2030 and 2050). Less than 10% of papers we reviewed had scenarios extending beyond 2050. For Africa, scenarios beyond 2050 are important. The African Union’s Agenda 2063 which is viewed as the blueprint for the continent’s development is tightly linked to the evolution of energy systems across the continent.

Secondly, most of the papers we reviewed considered very few scenarios in the models. Half of the papers had less than three scenarios, and over 90% of papers had a maximum of six scenarios. Considering the complexity and the multi-dimensionality of the issue at hand, one would expect to see a much larger number of scenarios, reflecting the uncertainties and normative choices that come to play in decision making at the nexus between economic development, energy transitions and emissions reduction.

4. Economic development is not a central element of current research

Of the papers we analyzed, only 10% considered development as an outcome of interest in energy transitions research. Most analysis prioritized climate goals and focused on determining the energy mix (90% of the papers) and the emission pathways (60% of the papers) needed to meet these goals.

For the papers that considered development as an outcome, projections of electricity consumption and economic growth were modest. The largest per capita electricity consumption projection for Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) in 2050 was 1,500 kWh, which is about half of the global average in 2017 and is far lower than OECD and U.S. consumption levels (7,992 kWh and 12,573 kWh, respectively) in 2017. These consumption targets seem to be driven by Africa’s historically low economic development and electricity demand and the assumption that these might not change much as we look to the future.

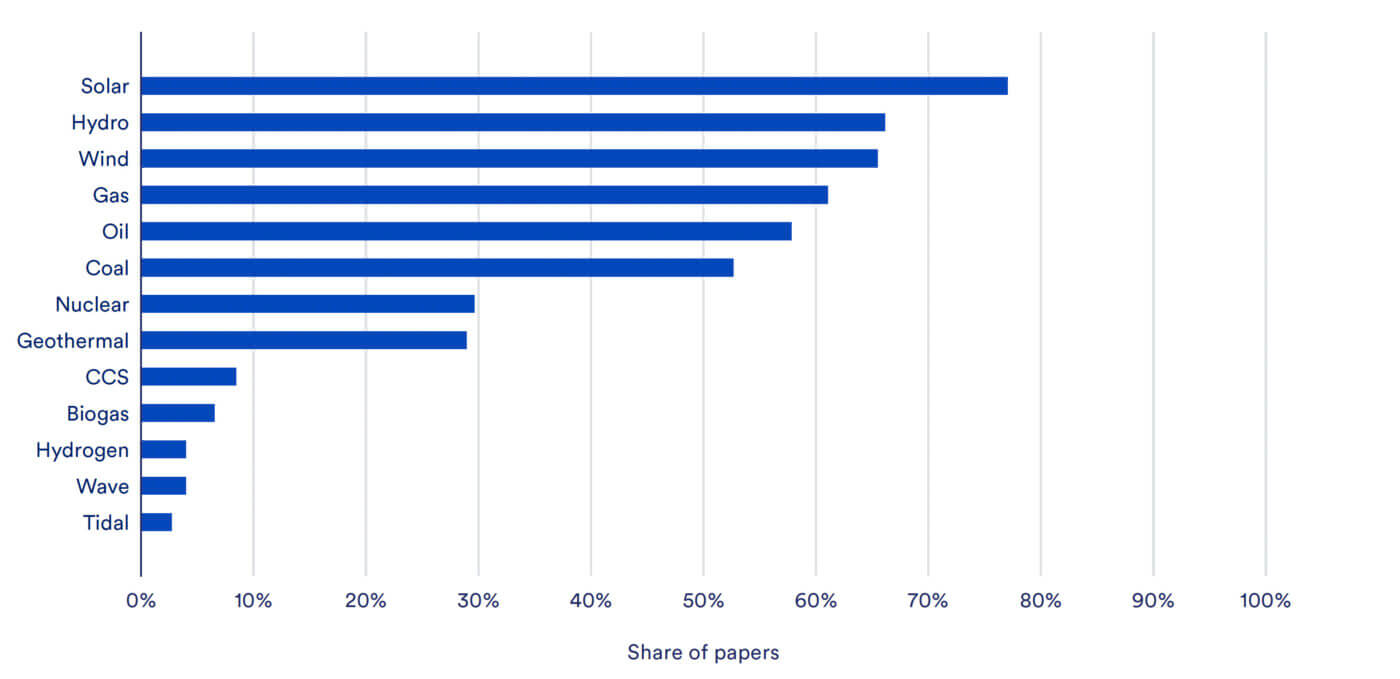

5. An exclusive set of technological pathways is considered

Solar, wind, and hydro are by far the technologies that are most considered in energy transition analysis in Africa (See Figure 3). Despite the global recognition (IEA, IPCC, and IRENA) that carbon capture, hydrogen, and nuclear energy will play a key role in achieving global net zero emissions, these are among the least studied technologies in the papers we evaluated. Giving limited attention to those critical energy technologies can inhibit understanding of the entire range of technologies that African countries will have to employ to meet their energy transition targets.

6. Energy transitions research in Africa is dominated by researchers based outside the continent

We also found that energy transitions research on Africa is dominated by researchers based outside of the continent (63%). 25% of the papers are produced by researchers based on the continent. We also assessed the potential policy influence of the literature and found that IPCC reports disproportionality cite (75%) papers produced by researchers outside Africa (See Figure 4). The fact that Africa-based researchers are less cited and less known in both international policy and scientific circles may explain why their intellectual contributions are under-represented in international policy reports. Regarding collaborative knowledge generation between the Global North and Global South, we found that only 12% of the papers featured such collaboration.

The way forward

Our study reveals interesting dynamics that are shaping energy transitions research and policy in Africa. Addressing the gaps we have identified will be critical to reshaping the intellectual and policy landscape for Africa’s energy transition. African governments and the international development community alike have a role to play. Supporting grounded and localized research and linking this to key policy decisions will ensure that all the complex pieces of Africa’s energy transition are well accounted for in global, regional and country-level climate strategies.

Originally published June 7, 2023 in African Arguments.