An introduction to the next clean energy frontier: Superhot rock geothermal and the power supply characterization of enhanced geothermal systems

This blog is part of a series exploring and explaining the science behind next-generation geothermal, with a special focus on superhot rock geothermal, through a curated tour of influential technical and academic papers. This edition highlights key features of the 2024 article by Aljubran and Horne, Power supply characterization of baseload and flexible enhanced geothermal systems. The full blog series, in addition to their reference reports, can be found at the Superhot Rock Resource Library.

Prior to the advancement of next-generation technologies, geothermal energy was limited to the few, scarce regions around the world with the three necessary components to develop conventional geothermal systems: shallow heat, abundant fluid, and interconnected rock fractures. Under those limitations, geothermal energy has only ever met less than 1% of the global energy demand. However, continued technological improvements could allow geothermal energy to expand geographically and meet as much as 15% of the global electricity demand growth to 2050. The advancements that created this opportunity have been driven by technological improvements including: 1) faster drilling rates and lower drilling costs, 2) higher production temperatures and flow rates, and 3) the development of longer and deeper wells. A key aspect of where next-generation geothermal will be developed in its early stages depends on the geothermal gradient of the region (i.e., how fast temperatures increase with depth below the Earth’s surface). This is because regions with shallow heat require less drilling to get to the same temperature when compared to regions with deeper heat resources. Continued improvements in these areas will be critical to turning this promise into reality—allowing geothermal energy to provide cost competitive clean firm power anywhere it is needed.

But how does this global potential translate to regional potential? In their 2024 article, Power supply characterization of baseload and flexible enhanced geothermal systems, Aljubran and Horne discuss a new temperature-at-depth model for the contiguous United States and use that model to determine the economics of developing enhanced geothermal systems across the contiguous U.S. This work, which I highlight below, showcases the potential cost competitive development of next-generation geothermal across the U.S.

Enhanced geothermal systems could generate more electricity than 300x the 2023 U.S. power consumption

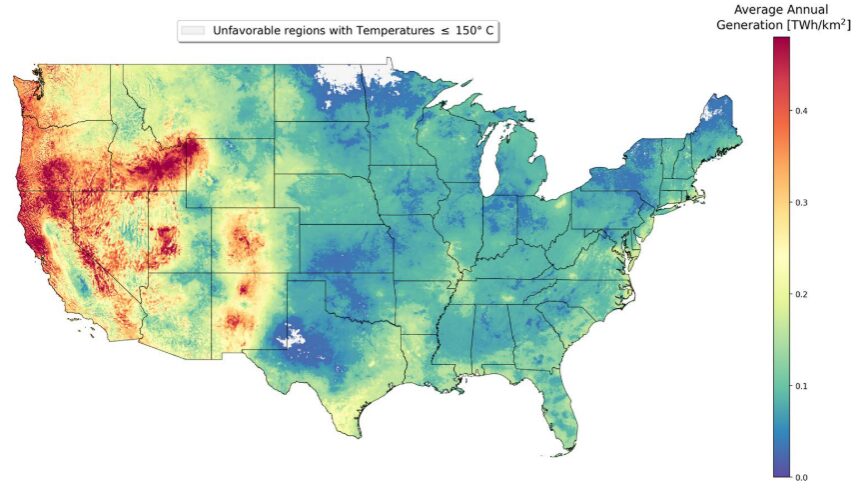

Aljubran and Horne developed the Stanford Thermal Model to estimate the potential of enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) across the contiguous U.S. at depths of up to 7 km. To do this, the Stanford Thermal Model estimates temperature-at-depth across the contiguous U.S. and is built on over 400,000 bottomhole temperature measurements in addition to other variables that are key to creating an accurate model of the subsurface. These additional variables include physical quantities such as depth, elevation, sediment thickness, magnetic and gravities anomalies, radioactive flux, seismicity, electric conductivity, and proximity to faults and volcanoes. All estimates assumed the use of Organic Rankine Cycle power plants across all operating temperatures with a project lifetime of 25 years.

Using this model, Aljubran and Horne estimate that the annual net generation potential for EGS is over 300 times greater than the 2023 U.S. power consumption of 4,014 Terrawatt hours (TWh) (Figure 1). Although, it is important to note that much of that potential is between 6-7 km – indicating the need for improvements in drilling technology to help lower costs at these greater depths. Their results underscore the potential of EGS across the entire contiguous U.S., contingent on continued technological advancements in drilling technology, and highlights the value of detailed geologic mapping to identify regional opportunities.

Figure 1. Average annual EGS generation per unit area for projects spanning 1-7 kilometers in depth

Drilling deeper can lower costs

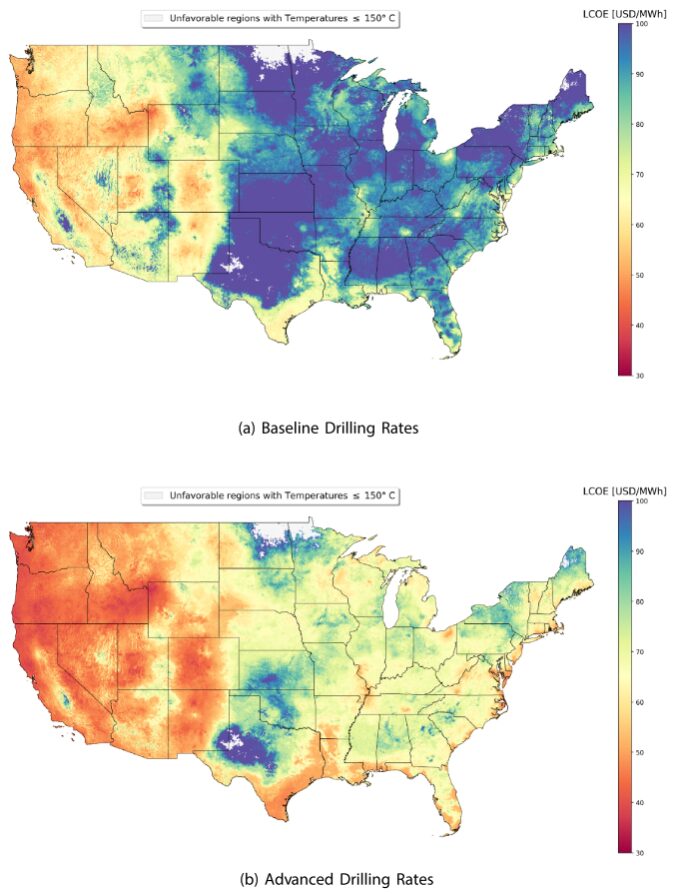

In addition to the mapping of EGS resource capacity, Aljubran and Horne also used their model to estimate the economic viability of EGS projects across the contiguous U.S. based on capital expenditure (CAPEX), operational expenditure (OPEX), and generation over time, which is represented as levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) across the contiguous U.S. in Figure 2. These estimates assume a discount rate of 7%, which reflects the future costs and energy production that have been converted to their present-day value. Their calculations also assumed an investment tax credit (ITC) of 30%, indicating the importance of federal tax credits to continue advancing early-stage technologies, such as next-generation geothermal. This was also documented in recent research by Ricks and Jenkins, where the ITC was critical to the successful scale-up of EGS technology in their simulations.

In addition to accounting for the LCOE, which takes into account the CAPEX, OPEX, and generation over time, Figure 2 shows how costs differ between using baseline drilling rates and advanced drilling rates. The advanced drilling rates are based on learnings from recent EGS projects, which demonstrated drilling cost reductions of nearly 50% after drilling approximately three wells. Use of advanced drilling rates resulted in an LCOE reduction of nearly 25% on average.

Figure 1. Optimal levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for EGS development across the contiguous U.S. for (a) baseline and (b) advanced drilling rates

Aljubran and Horne found that LCOE was lowest for nearly 90% of the contiguous U.S. by drilling to the deepest point of their studied depth (i.e., 7 km). LCOE was optimized at shallower depths (≤4 km) in a few regions across the western U.S. with high geothermal gradients (e.g., the Snake River Plain or the Great Basin) or where the geothermal gradient becomes more gradual with increasing depth (e.g., western North Dakota). This was attributed to increasing drilling costs with depth that don’t justify the benefit of a higher resource temperature.

What’s next?

Research by Aljubran and Horne illustrate the potential for EGS deployment across the contiguous U.S. Their research shows the large potential for EGS – potentially more than 300x the 2023 U.S. power consumption. It also shows the importance of thorough characterization of local and regional geology to understand resource potential. Additionally, their work determined that in many regions, such as those without exceptionally shallow heat resources, it makes economic sense to drill to deeper depths to maximize heat (i.e., 7 km). This is especially true with continued drilling rate improvements that have been documented in recent EGS projects.

Stay tuned for more from CATF as we continue to push forward bold ideas on how to scale higher enthalpy geothermal as an essential form of clean firm electricity anywhere it is needed.

This blog is part of a series exploring and explaining the science behind next-generation geothermal energy, with a special focus on superhot rock geothermal:

Through a curated tour of influential technical and academic papers, the series aims to provide a fresh perspective from a geoscientist entering the geothermal industry. The goal is to share my learning journey and encourage collaboration around these groundbreaking solutions, which are critical to achieving a clean energy future. Whether you’re new to geothermal or looking to deepen your knowledge, I hope this series offers valuable insights into this fast-evolving field.