The Role of Middle East Leadership in Clean Energy Infrastructure Funding: Can the Middle East Fill Africa’s Energy Finance Gap?

UAE and Saudi Arabia Case Studies

Authors:

Nada Hamade, Consultant, Clean Air Task Force

David Yellen, Director, Climate Policy Innovation, Clean Air Task Force

Introduction

Financing for energy infrastructure remains a critical challenge for both development and climate action globally, and particularly on the African continent. Most African countries lack adequate energy infrastructure and access to sufficient capital to fill the gap. More than 600 million people still lack reliable access to electricity, a critical enabler of development and growth. Yet clean energy spending in Africa stood at $25 billion in 2022, only 2 percent of the global total, while around $133 billion is needed each year from 2026 to 2030 to achieve clean energy and climate goals, according to the International Energy Agency’s Africa Energy Outlook 2022. The United States’ pullback from development funding, Europe’s fiscal constraints with accelerating security and health spending, and China’s reduction in funding will all widen the gap. New sources of financing are critical to unlocking the continent’s vast potential and realigning development imperatives with climate action. Fortunately, new and growing funders are emerging among neighbours in the Middle East.

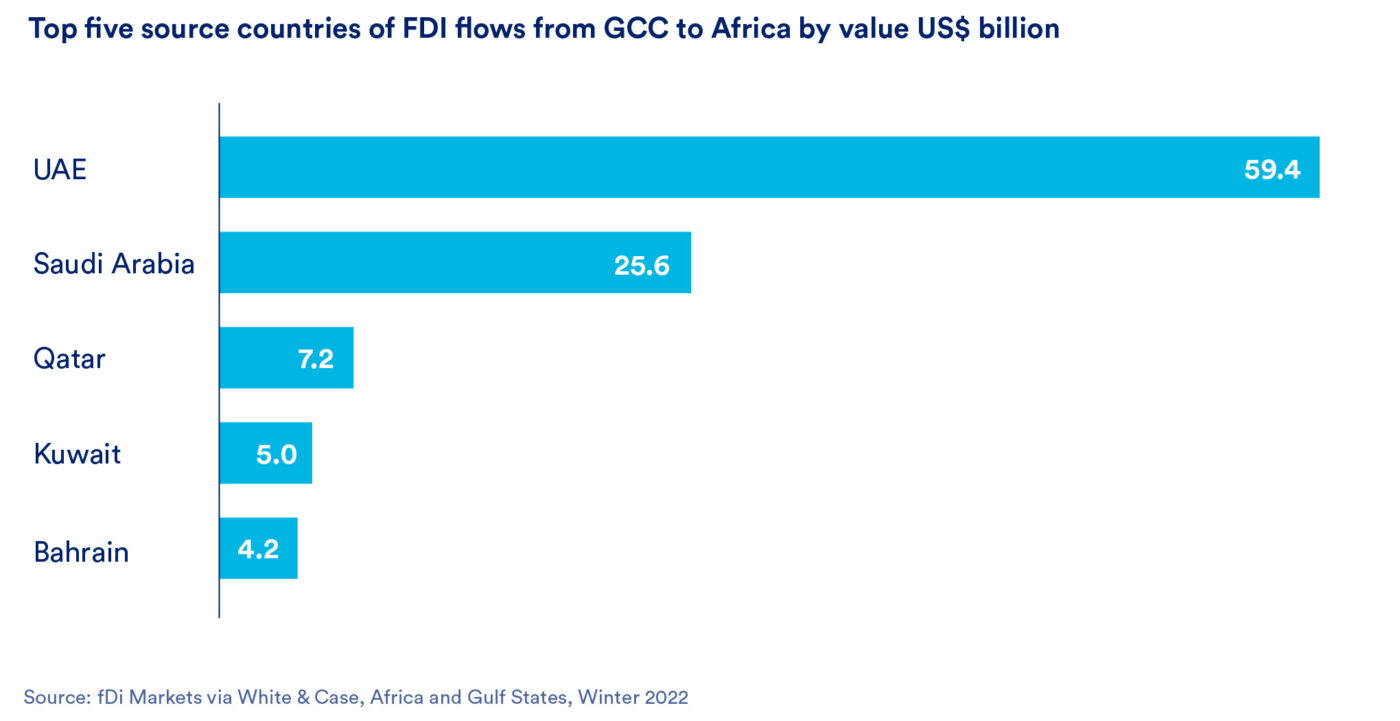

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are among the world’s largest international donors, frequently among the only countries in the world to surpass the 0.7% Official Development Assistance/ Gross National Income target. The Gulf’s role has grown rapidly over the past few years, catapulted by economic and geopolitical leadership interests, and clean energy projects have begun to play a larger role in overseas investment. In that context, the rise of the Middle East—and the leading members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in particular—as a new, growing source of international infrastructure finance comes at an opportune time.

The GCC nations are critical to the ongoing effort to decarbonize the global energy system, owing to both their outsized role in that system and their investments into decarbonization technologies. Recognizing the imperative to address climate change—and the diplomatic and economic opportunities offered by the global effort to do so—GCC nations have committed substantial resources to develop and deploy clean energy solutions at home and abroad, diversifying their energy portfolios. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar in particular can play a transformative role in the global energy transition, including as investors and financiers in emerging economies. While Qatar has begun to increase its clean energy investment footprint, it remains at an earlier stage compared to the UAE and Saudi Arabia—but has significant potential to follow suit given its financial capacity and growing interest in the sector.

Beyond the GCC countries’ investments in clean energy globally, they have made investments across a range of industries, from technology and infrastructure to finance and artificial intelligence, to bolster their economic competitiveness and expand into new industries.

The GCC has taken an active role in global political dynamics, diversifying alliances to partner more closely not just with OECD countries, but also with China and Russia as well as other major emerging economies. In particular, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are increasingly positioning themselves as key players in shaping the future of international markets, with the UAE having joined BRICS in 2024 while Saudi Arabia is still mulling the prospect. And both countries have sought leadership roles in international clean energy and climate action, with the UAE notably hosting the COP28 climate conference. With a unique role in global geopolitics and the energy system, the GCC has an opportunity to distinguish itself further by carving out a new role in infrastructure finance that seeks to build new markets and industries in emerging economies.

This report explores Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s ambitions as global financers of clean energy and characterizes the role that GCC international finance could play by examining the clean energy and climate-focused funding flows from the UAE and Saudi Arabia to emerging economies in Africa at a high level.1 While rising investment can be a major force for development and clean energy deployment on the continent, GCC countries can drive far deeper impact by adopting a partnership-driven development approach, diversifying their funding across countries on the continent to include less-developed partners, and incorporating system investments that reduce risk for other projects, rather than concentrating on generation projects.

The Finance Gap in Africa

Reliable access to electricity and clean cooking methods remains a major challenge on the African continent. The continent accounts for about a fifth of the global population, yet less than 6% of annual energy consumption. Achieving universal electricity access and clean cooking would require about $30 billion and $4 billion per year, respectively, to 2030. Doing so with only clean energy sources would be even more expensive. Yet sources of public capital to address those gaps are severely limited for many countries on the continent, which already face untenable debt burdens. The cost of capital for projects across the continent is far higher than those used in international institutions’ assumptions, making borrowing to fill the gap even more difficult. The International Energy Agency attributes this to a combination of political instability, shifting regulations, elevated sovereign risk, limited financial-market depth, and persistent currency volatility. Projects are often financed in foreign currency while the money made is in local currency, so any exchange-rate swings adds extra risk. All of this makes capital expensive, impeding investment even when the long-term potential is high.

Despite challenges, the opportunity for clean energy development in Africa is immense. Africa is endowed with abundant clean energy resources that include solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, as well as key upstream resources like precious metals. It has the potential to emerge as a hub and propeller of clean energy around the world. The Economic Commission for Africa has highlighted the need for countries on the continent to scale up green and resilient infrastructure development in order to realize its vast potential for renewable and clean energy. But without sufficient financing available to build the projects—and the enabling infrastructure necessary to actually deliver power to the customers that need it—many projects remain unviable.

The finance that does flow to the continent from development institutions and international investors is both limited and directed toward only a small subset of the continent. According to Bloomberg, clean energy investment in Africa is concentrated in a few countries: South Africa, Egypt, Morocco, and Kenya. These countries were the recipients of $46 billion between 2010 and end of 2021, which accounts for 3/4 of all renewable energy investments in Africa during that period. These four markets have historically had stronger institutions and more predictable regulatory frameworks than most African peers, and they benefit from strategic geopolitical positioning: South Africa’s BRICS membership, Egypt and Morocco’s proximity to Europe, the Gulf, and major North African export corridors, and Kenya as East Africa’s regional economic hub. Yet while all four countries have important needs in their power sectors, they are among the 10 African countries with the highest electricity access on the continent and have access to cheaper capital—for the very reason that they are attractive investment markets, they have less strong need for patient capital.

The Role of the Gulf

The GCC countries have an opportunity to play an integral role in helping fill this finance gap by leveraging their resources, energy infrastructure development expertise, and proximity to the African continent. And where other funding sources have saddled the continent with debt, Gulf countries can forge new investment patterns, focused on market and value creation rather than deepening debt and enabling aid dependency. GCC sovereign funds are being invested in clean energy projects that could benefit both the Middle East and Africa’s transitions into green industrial hubs.

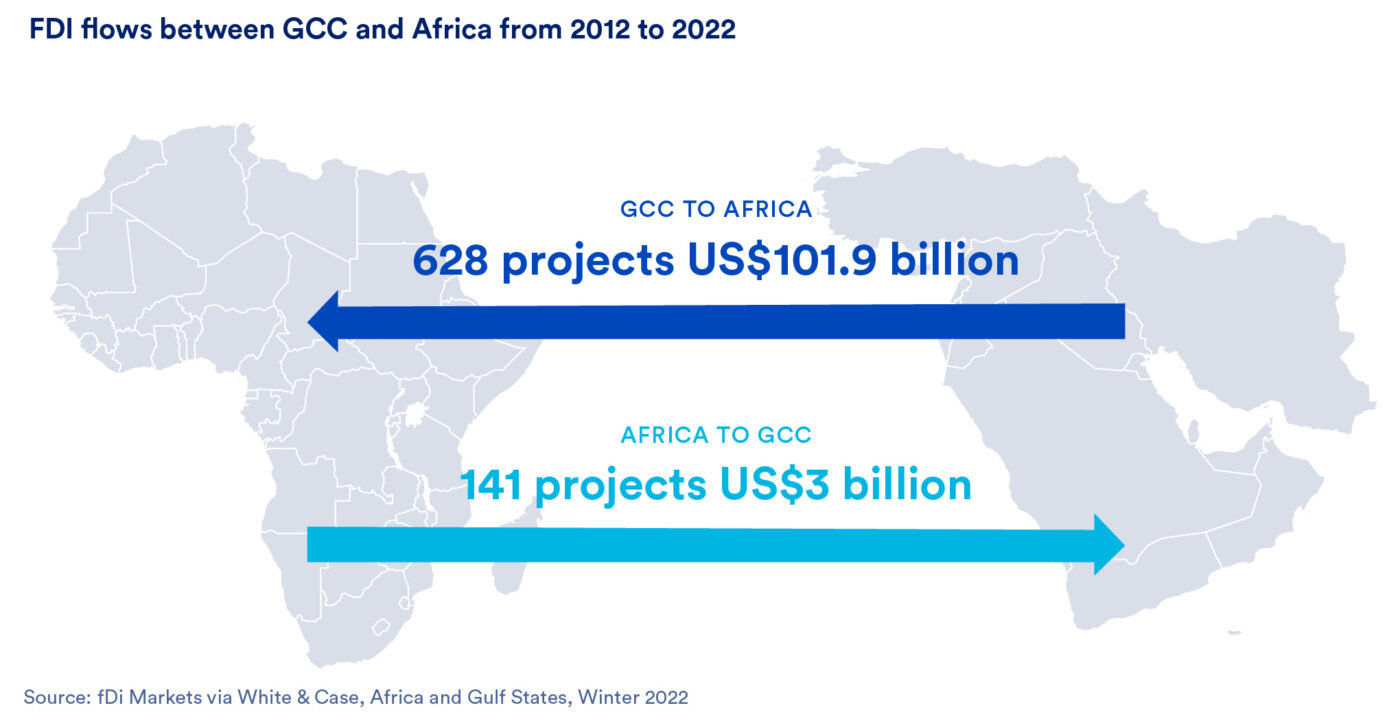

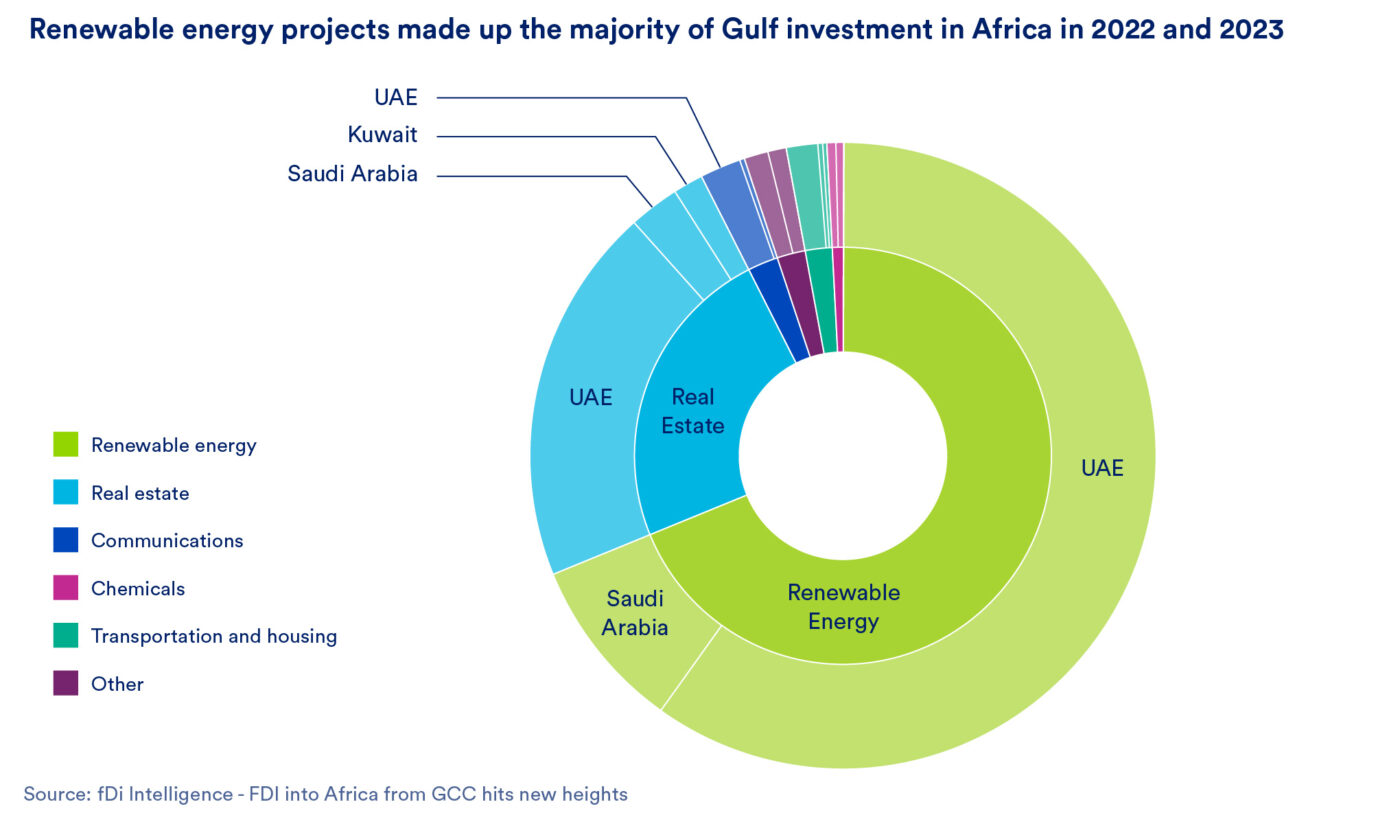

In 2022, GCC investors announced $60 billion across 83 projects in Africa, according to FT Locations data. More than 90% of this FDI originated from the UAE and Saudi Arabia, with the majority directed towards hydrogen and other renewable-energy projects.

Growing investment from the GCC opens an avenue for maintaining effective partnerships between the GCC and Africa that can benefit both regions and catapult them to long-term competitiveness and leadership in clean energy markets. Perhaps most importantly, GCC countries are accelerating investment at the same time as development funding from the US and Europe is thrown into question, and doing so in a way that can set the region apart. GCC countries have so far invested in projects as market opportunities, looking for returns on investment from project success, strengthened partnerships on the continent, and stronger markets for future business.

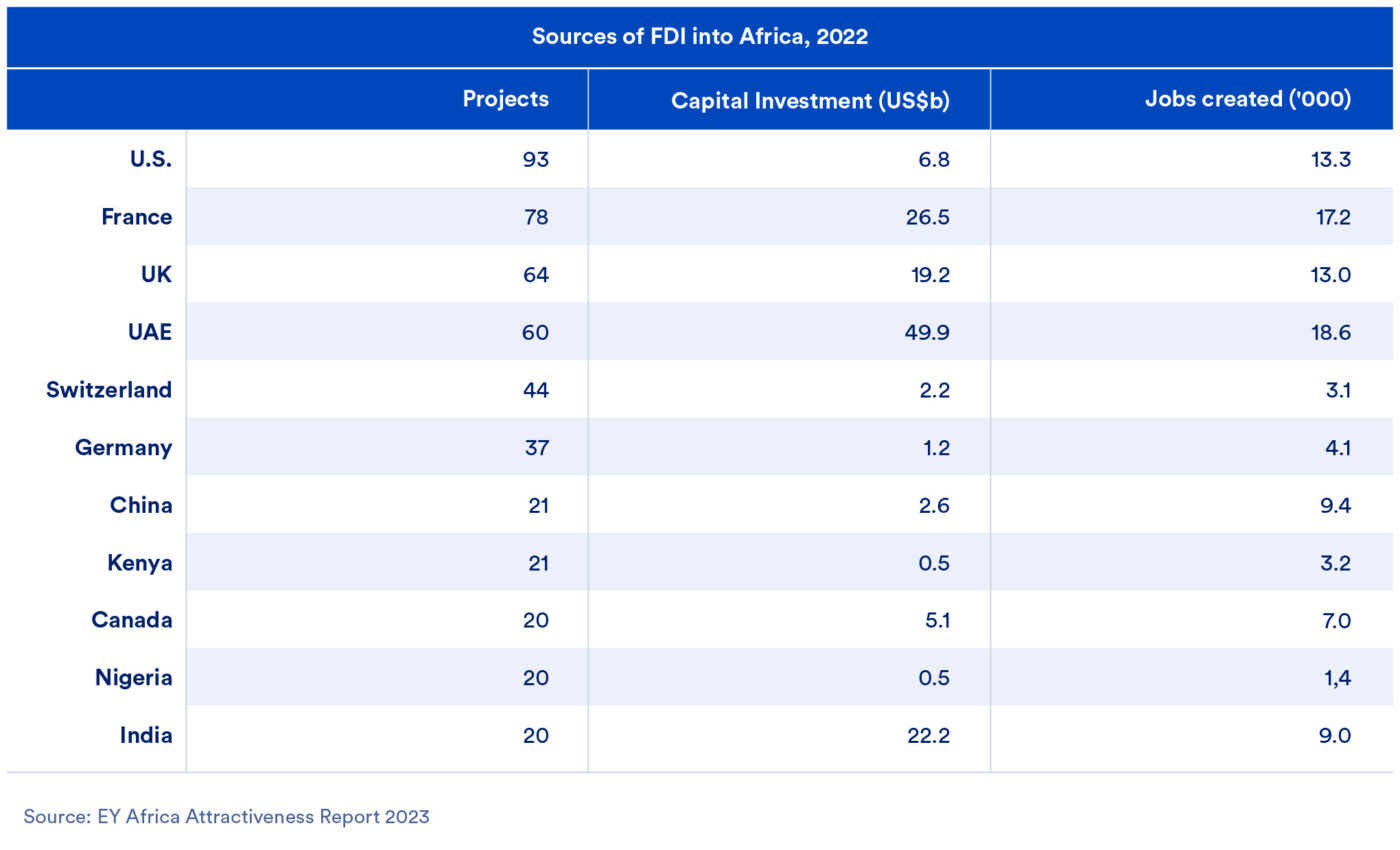

While not considered “development aid,” this investment pattern avoids adding to African countries’ debt burdens and incentivizes longer-term partnerships and investments to maximize returns. And while such investment would normally require low project and investment risks, GCC countries can invest with a higher risk appetite than international institutional investors, creating huge opportunities for large market impact where private capital would normally not invest, since sovereign-backed developers like ACWA Power and Masdar can pursue long-term strategic returns and capture early-mover advantages that traditional investors find too risky. This also aligns with their broader geopolitical objectives—expanding international influence, securing energy partnerships, and positioning the GCC in emerging clean-energy value chains—hence investing even where commercial risks might be high. Moreover, the GCC market development approach is credited with more job creation and skills development for the local community. In 2022, FDI projects from the UAE to Africa created the most employment of any country’s investments, with more than 18,000 jobs created. A more diverse funding pool for infrastructure projects—both from different countries and deployed through different mechanisms—can drive more progress and improve African countries’ positions. As with fuel supply chains, diversifying funding sources reduces dependence on any single provider, thereby limiting the leverage of any individual investing country.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE each bring expertise in clean energy and decarbonization technologies that they deploy or fund locally and abroad. These include carbon capture and storage (CCS), solar, wind, hydropower, nuclear, geothermal, hydrogen, critical mineral mining, cable technology, and others. Over the past several years, each country has also rapidly increased its financing and financing commitments for clean energy projects in Africa.

In evaluating each country’s energy and climate financing in Africa, we focus on three key metrics:

- Quantity and character of finance: How much total financing has been directed toward clean energy projects, in what form, and over what number of projects?

- Destination: Which countries are receiving the bulk of GCC financing in Africa?

- Types of project funded: Which technology and project types receive most GCC funding?

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

As part of its growing leadership on climate action globally, the UAE invested more than $50 billion in clean energy projects in 70 countries by 2022. The UAE has accelerated its investment in clean energy projects in Africa since 2020. According to OECD figures, UAE development climate funding abroad from 2012–2021 totalled $1.23 billion, 83.65% of which was given as grants, while the rest was loans. Between 2019 and 2023, Emirati companies announced $110 billion of projects in Africa, $72 billion of them in renewable energy, according to FT Locations.

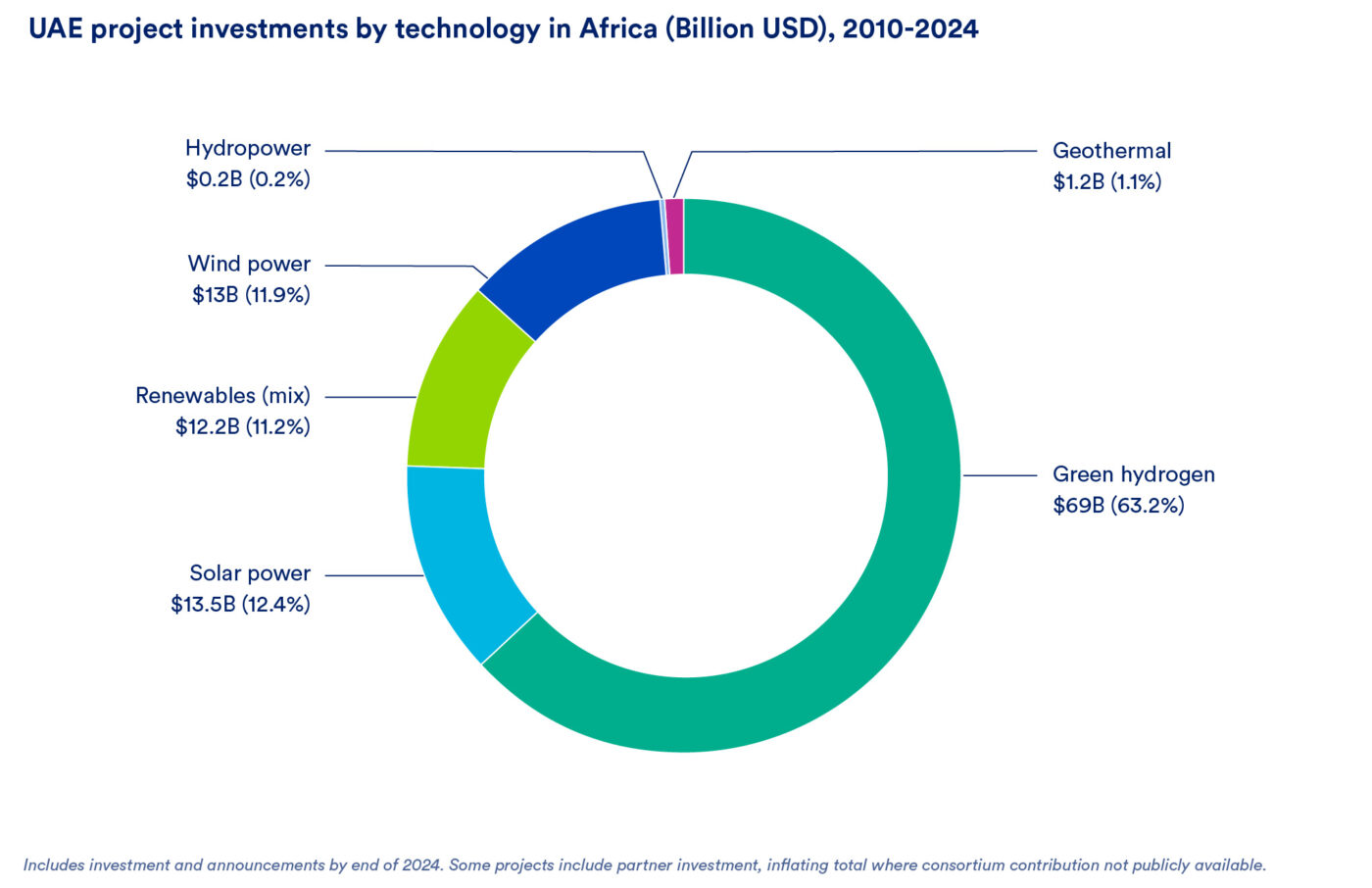

CATF compiled publicly announced clean energy projects and agreements in developing countries funded directly by UAE governmental and semigovernmental entities (alongside international partners in many instances) from 2010 through the end of 2024. Out of 135 total projects and agreements identified globally, 80 were solar, 19 were wind, seven were hydropower, and 21 a combination of these renewables. We also identified four geothermal and four green hydrogen agreements.

Though most projects were solar power generation, the handful of green hydrogen projects represent an outsized share of total announced investment. Since 2022, there has been a shift toward larger, billion-dollar projects. 34 multi-billion-dollar investments have been announced between 2022 and 2024, half of which are in Africa (18). Since 2020, the bulk of the UAE’s project investments abroad have been led by Masdar, the country’s leading clean energy developer.

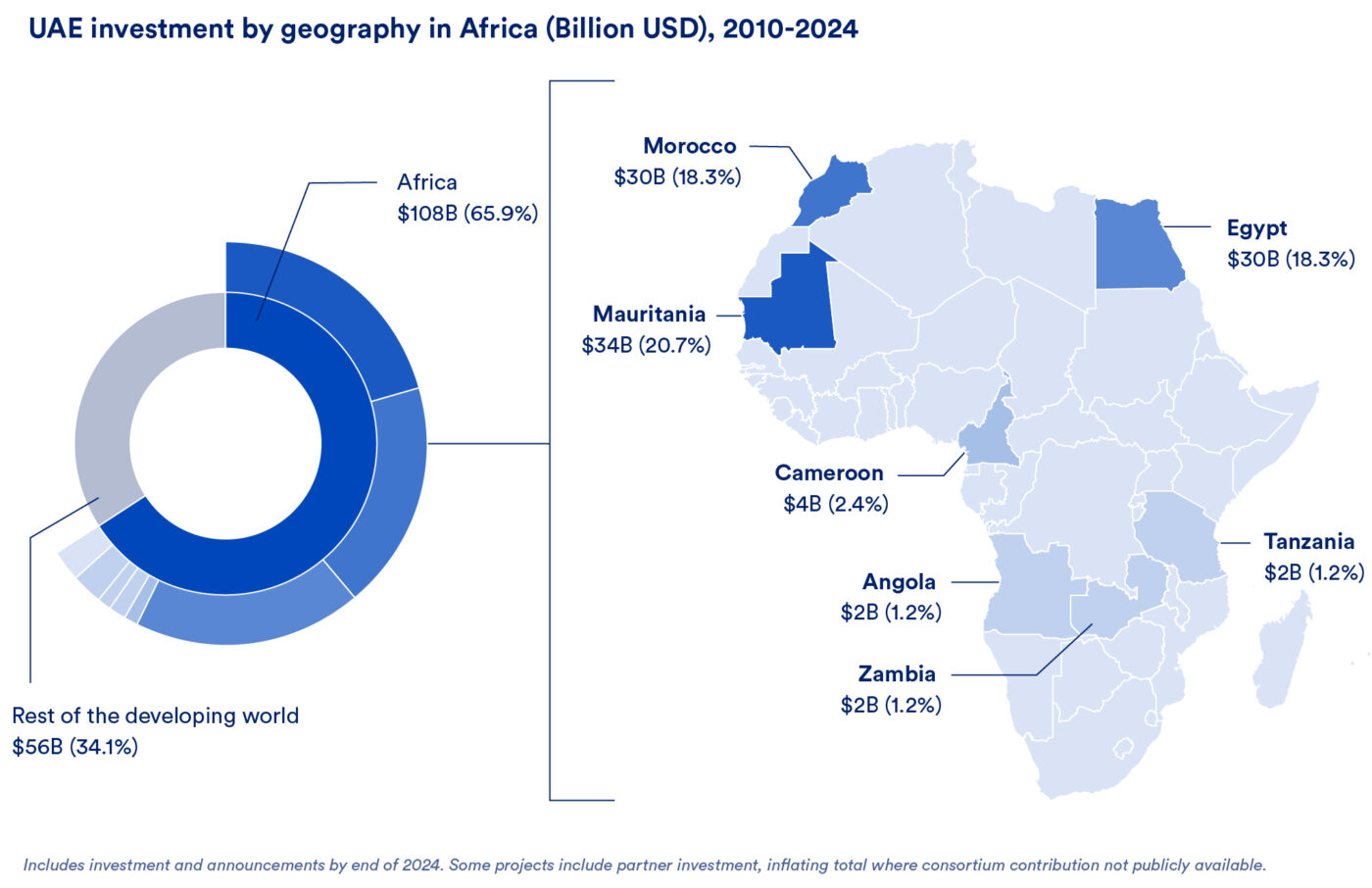

Total UAE investment and announced funding for projects in clean energy in Africa from 2010 to 2020 amounted to less than $1 billion. From 2020 through 2024, planned and announced projects are worth close to $108 billion (this total includes co-investment with partners—the relative shares of which are not all public). Of that total, between unilateral and co-funded projects and agreements since 2022, around $38 billion was intended for renewables and around $69 billion for planned hydrogen projects.2

- Mauritania: A $34 billion green hydrogen project with a production capacity of up to 8 million tonnes of green hydrogen per year, with an electrolyser capacity of up to 10 GW. The investment consortium includes the Egyptian developer Infinity, Masdar, and the German “Conjuncta,” with the first 400 MW phase of the plant expected to be operational by 2028.

- Egypt: A 4 GW green hydrogen project with an output of up to 480 thousand tons of green hydrogen per year, as well as a 10 GW wind power project.

- Morocco: TAQA Morocco announced it will invest $27.2 billion into a 6 GW green hydrogen project in Morocco.

Many of the billion-dollar projects fall under the umbrella of the Etihad 7 Initiative, which was launched by the UAE in 2022 and aims to provide 100 million people across the African continent with clean electricity by 2035, while securing energy investments from both private and public sources.

At Africa Climate Week 2023, the UAE pledged $4.5 billion to finance Africa climate projects through Masdar, the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, Etihad Credit Insurance (the nation’s export credit agency), and AMEA Power, a private renewable energy company. AMEA power’s projects are not included in these calculations, as the data solely includes projects in which governmental and semi-governmental entities are involved. However, it is worth noting some UAE private entities are making significant investments in Africa, with AMEA power planning a $15 billion dollar hydrogen investment in the continent and Ocior Energy agreeing to invest $4 billion in a green hydrogen and ammonia project in Egypt. AMEA Power alone has around 2.5 GW of renewable projects in operation and under development in Africa.

During the 2023 Africa Climate Summit, it was announced that Masdar will work with the AfDB’s African infrastructure investment platform Africa50, which expands clean growth through blended public and private finance solutions, by identifying, fast-tracking and scaling clean energy projects. Masdar has committed a total of $10 billion in clean energy finance which will target the delivery of 10GW of clean energy capacity in Africa by 2030, of which $2 billion will be generated from equity, with an additional $8 billion mobilized from project finance. Masdar’s portfolio with partners includes Senegal’s first utility-scale wind farm, Mauritania’s first and largest solar photovoltaic project, and the development of Africa’s largest wind farm in Egypt.

UAE’s announced project investments have thus ballooned over the past five years, with particular focus on renewable energy and hydrogen technologies. Still, with most commitments and projects expected over the next few years, the number of projects that reach a final investment decision and share of announced capital that is transferred remains to be seen.

Several recently announced UAE-funded clean energy projects in Africa have progressed, with some breaking ground and others advancing through preparatory stages. In May 2024, Masdar, alongside partners, signed a land access agreement with the Egyptian government for the 10 GW onshore wind farm in West Suhag. Masdar also signed a concession agreement with Angola for the first 150MWac solar PV project in Quipungo under Phase I of the 2GW renewable energy collaboration between the governments of the UAE and Angola. Similarly, Masdar and Uganda signed a roadmap agreement for the implementation of a 150MW Solar PV project under Phase I of the 1GW collaboration between the two nations.

The UAE has funded many smaller scale projects that have been completed as well, including small-scale solar plants in Egypt, Somalia, Togo, Sudan, Mauritania, Seychelles, and solar home systems in Morocco and Egypt. Their focus shifting toward larger utility-scale projects promises far higher potential impact.

In an effort to revolutionize the climate finance landscape, the UAE announced at COP28 a $30 billion commitment to ALTÉRRA, a new fund aiming to mobilize $250 billion by 2030 for climate investments and improve financing for the Global South. In 2024, Alterra committed $6.5 billion to seven strategies managed by BlackRock Inc., Brookfield Asset Management Ltd. and TPG Inc.

Looking ahead, the UAE is still channelling huge investments into the continent, as Morocco is in negotiations with several UAE entities for wind energy projects in the southern provinces in Western Sahara valued between $8 and $10 billion, with a production capacity reaching 5 GW. The UAE and Morocco also signed a $14 billion deal in 2025 that includes 1.2 GW of renewable energy capacity (solar and wind) alongside a 1,400 km HVDC transmission line for inland exports.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has similarly indicated its interest in being a larger player in clean energy, scaling up carbon capture technologies and clean hydrogen not only domestically, but at a regional level as well. The country is targeting 650 GW of renewable energy by 2060 and is willing to invest up to $266.40 billion to generate cleaner energy and add transport lines and distribution networks for clean hydrogen production and export.

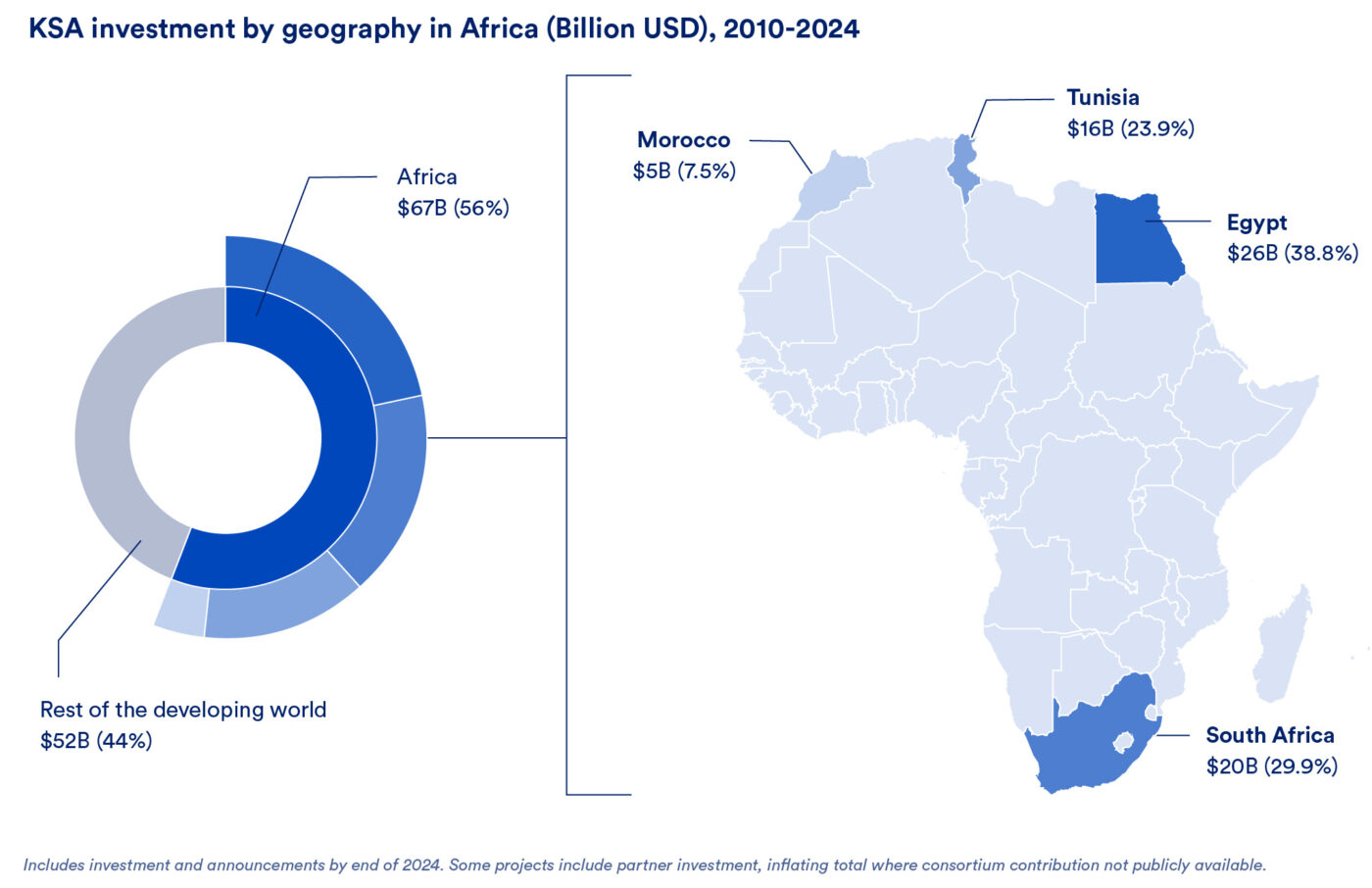

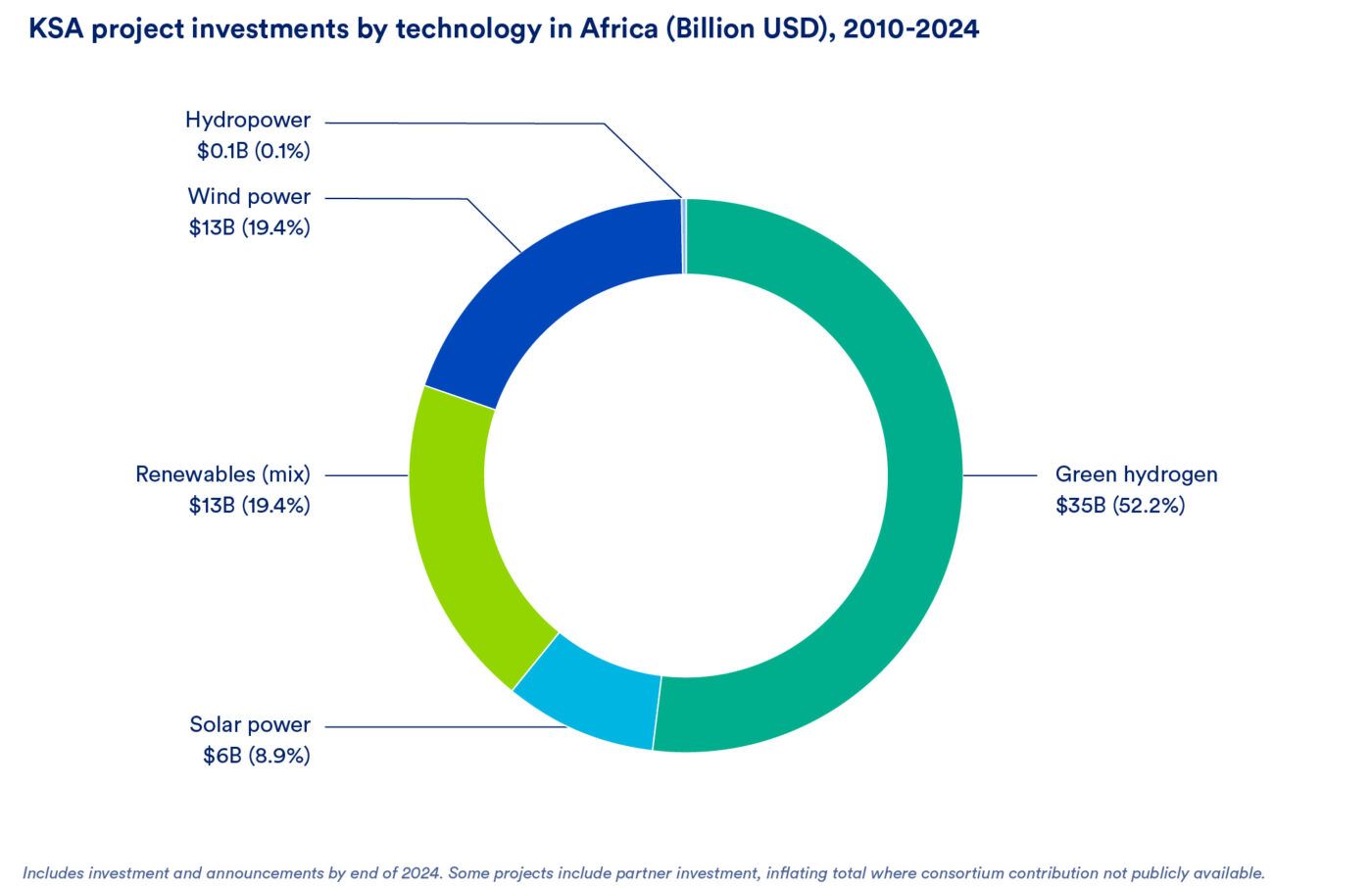

As with the UAE, Saudi Arabia has rapidly increased the scale and scope of its infrastructure investment abroad since 2022. For the 51 clean energy projects identified that were announced, funded, or co-funded between 2010 and 2024 by Saudi governmental and semi-governmental entities, almost half were in Africa (23), dispersed over 5 countries. All $1B+ projects but one were announced between 2022 and 2024, with nine out of 17 such projects in Africa. Similar to UAE funding patterns, most funding prior to 2014 went toward hydropower projects funded by the Saudi Fund for Development, but this has since shifted to variable renewables and hydrogen/ammonia projects with funding from ACWA, a Saudi energy and desalination project developer. Most investment has been deployed by ACWA and the Saudi Development Fund, with the projects announced by ACWA with partners accounting for around $100 billion.

Saudi Arabia’s clean energy funding in Africa between 2010 and 2021 amounted to around $4 billion. From 2022-2024, planned and announced projects totalled more than $62 billion (most of which is contributed solely by Saudi Arabia).

- Egypt: A 10 GW wind power project worth $10 billion that will generate nearly 50,000 GWh of clean energy annually and provide electricity to approximately 11 million households.

- Egypt: A green hydrogen project worth $4 billion with a capacity of 600,000 tonnes-per-year of green ammonia, with the intention of scaling up to a second phase with a potential capacity of 2 million tonnes-per-year.

- South Africa: A $10 billion MOU with the Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa to explore the development of green hydrogen and its derivatives.

Since 2022, around $28 billion of Saudi Arabia’s investment announcements in Africa with partners have been allocated to renewable projects, with approximately $35 billion to hydrogen projects.

Egypt and South Africa account for the vast majority of Saudi Arabia’s investments in Africa. South Africa’s government indicated that Saudi Arabia and the UAE were within the top five most significant renewable energy players in the African market in 2022, with ACWA Power in first place. ACWA Power aims to invest $10 billion over the next few years in South Africa, which serves as the first market for ACWA Power’s broader green hydrogen plans in Africa. Egypt, meanwhile, is looking to position itself as a regional hub for hydrogen production. The country has signed a number of MOUs recently, including a $3.5 billion green hydrogen project by Saudi Arabia’s AlFanar in addition to a $4 billlion hydrogen/ammonia agreement with ACWA. ACWA Power had already invested $2.5 billion in Egypt’s renewable sector alongside an impressive $10 billion wind power plant, as it announced plans to pump $10 billion into the country by 2026.

Saudi Arabia has taken several steps to promote its influence in clean energy development in Africa, on top of these investments. Saudi Arabia launched the ‘Empowering Africa Initiative’ at MENA Climate Week 2023 in Riyadh, which aims to assist African countries in meeting the challenges of obtaining reliable and sustainable energy supplies at the most affordable costs, by bringing in cleaner energy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution. The above investment totals include only recent announcements that have specific dollar amounts attached to them, not recent MoUs with other African countries like those signed in 2023 with Ethiopia, Senegal, Chad, Nigeria, and Rwanda at the Saudi-Arab-African Economic Conference, which still do not have specific allocation amounts or defined projects. Earlier in 2024, Saudi Arabia also signed an MoU with the government of Mauritania to cooperate in the renewable energy and clean hydrogen sectors, including on CCS. ACWA Power is a lead shareholder in South Africa’s 50 MW Bokpoort CSP Plant which has been operational since December 2015, while the 442 MW ACWA DAO solar PV power project is expected to enter into commercial operation in 2026. Other operational projects financed by ACWA include Morocco’s 510 MW Noor Ouarzazate CSP and PV Project and 200 MW solar PV project in Egypt.

Momentum has continued. In October 2024, Saudi Arabia pledged at least $41 billion for development projects in sub-Saharan Africa, with an undisclosed share allocated to clean energy and infrastructure. More recently, in 2025, ACWA Power signed a $2.3 billion deal to develop a 2 GW wind farm in Egypt and is set to finalize the first phase of the company’s green hydrogen project in the Suez Canal Economic Zone in the fourth quarter of 2028.

In a Snapshot: Overview and Patterns in GCC Clean Energy Investment Across Africa

Quantity and character of finance

From 2010 through 2024, clean energy bilateral funding and announcements from the UAE and Saudi Arabia alongside partners towards Africa totalled more than $175 billion, with most funding in the form of direct project investment, rather than as loans. The huge commitments made by the likes of ACWA Power and Masdar into renewable energy projects in Africa are overwhelmingly structured as commercial investments. Grants and concessional loans with favourable terms are more often associated with development agencies and sovereign funds such as the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development and the Saudi Development Fund.

Destination

GCC governmental and semi-governmental entities (which are partially owned by the government) have collectively entered clean energy partnerships with or made project investments into around half of African countries, but the vast majority of the funding has gone to a handful of countries, notably Egypt, Morocco, and South Africa, with big commitments also made recently to Mauritania. The GCC countries are thus directing the bulk of their investment to the same countries that have historically received the most funding from international development institutions, where the investment risk is lowest, but the impact is also reduced relative to what could be achieved if the GCC struck a new path.

Types of project funded

Prior to 2015, the focus of GCC clean energy finance was mainly on hydropower, with a subsequent shift to solar, wind, and hydrogen. The vast majority of announced finance in the past decade has been directed toward renewable energy generation and hydrogen projects. Billion dollar and multi-gigawatt projects have emerged more frequently since 2022 through multiple agreements, acquisitions, and plans. There is no guarantee that these planned ambitious projects will all reach final investment decision (FID), and experts raised concerns that certain countries may lack the capacity to handle such huge projects, some of which eclipse their own GDP. Additionally, some projects may ultimately be shelved or re-scoped as market realities shift—particularly in emerging segments such as green hydrogen, where costs, off-taker certainty, and infrastructure requirements have proven more challenging than early expectations suggested. However, the potential reprioritization of technologies should not be seen as a setback. Rather, it represents an opportunity for GCC investors and partner countries to reallocate pledged capital toward other strategic clean-energy and decarbonization solutions. By remaining flexible and reinvesting capital into commercially viable and context-appropriate clean technologies, GCC partners can strengthen resilience, accelerate energy transitions, and diversify Africa’s clean-energy landscape in line with long-term climate and development objectives.

Reshaping Finance for Deeper Impact: Going Beyond Solar, Wind, and Hydrogen

The vast majority of outward clean energy funding from GCC countries has been directed to variable renewable generation and hydrogen projects. While these projects are an important avenue, particularly given the huge renewable power potential of the African continent, funding has so far avoided other technologies and project types. Funding from the GCC nations is also concentrated in only a few countries, typically in those that already receive the most funding from development finance institutions and foreign direct investment. Diversifying into other countries can expand the impact of investment, further distinguish the GCC from other funding sources in seeking to develop and build markets, and ensure the clean energy transition does not result in asymmetric development. Geographic and project diversification is a key next step for GCC financing. It can help recentre the continent’s energy-access needs while strengthening partnerships more broadly and setting the region apart from legacy sources of development funding that have failed to meet their objectives. To enable deeper and more durable impact for developing markets in Africa, strengthening GCC partnerships in the region, and enabling decarbonization in the long term, the GCC should explore prioritizing finance for projects in Africa that fall into the following project types:

Transmission and enabling infrastructure

Beyond generation, significant opportunities lie in enabling infrastructure—particularly grid development, extension, and modernization—which remain especially ripe for investment. Strengthening transmission systems can reduce bottlenecks, improve reliability, and create a more attractive environment for scaling up renewable deployment and catalysing further private-sector participation. Integrated planning of generation and transmission can improve investor certainty by better aligning projects with delivery infrastructure, reducing risk for both African countries and GCC investors. At the regional level, stronger transmission links can also improve African energy security by enabling cross-border electricity trade through existing power pools, such as the West African Power Pool (WAPP) and the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP).

Transmission and delivery infrastructure have significant ancillary benefits that outstrip those of generation projects. For one, creating a delivery system and reliable grid infrastructure can help to de-risk investment into power generation, making some projects viable for private finance that otherwise would require public investment. Renewable power generation projects are vital for increasing energy supply growth on the continent, but they have little value in the absence of reliable delivery infrastructure—this fact helps explain why funding for generation projects has been concentrated in those countries that already have higher rates of electricity access. These investments may be safer, and more easily classified as climate finance, but have far less sustainable impact than enabling infrastructure projects may.

The existing transmission infrastructure in Africa is inadequate, hindering the ability of many African countries to tap into their abundant renewable energy resources. Only 43% of Africans have access to electricity that works “most” or “all” of the time. While 98% of households in Mauritius and 95% of those in Morocco report reliable access to electricity, only 5% of Malawian households report so. Reliable electric service in cities stands at 65% in comparison to rural areas where it is reported at 24%. From an economic standpoint, electrical outages cost African firms around 5% of the value of total annual sales. Outdated and poorly maintained energy assets—including weak transmission networks—function as “zombie energy systems” that drain resources, perpetuate energy poverty, and impede progress toward reliable and equitable electricity access. Evidence from Benin shows that households facing unreliable electricity spend significantly more to on generators, batteries, and stabilizers in order to cope, pushing many into energy poverty even when they are technically connected to the grid. Meeting countries’ climate targets globally will require adding or refurbishing more than 80 million km of grid infrastructure, much of which will be needed in Africa.

Alongside physical grid infrastructure, digital systems such as smart meters and real-time grid-management tools will be central to Africa’s “twin transition” in clean energy and digitalisation, enabling higher renewable integration and more reliable, flexible power systems—an area where the UAE and Saudi Arabia already hold relevant operational expertise. Significant investments are needed to modernize and build flexible grid systems and facilitate integrated and well-functioning regional power markets to drive a clean energy future in Africa. McKinsey estimates a $400 billion investment in transmission and distribution is needed in Africa by 2050 in order to enhance grid reach, resilience, and flexibility alongside essential battery energy storage. The International Finance Corporation estimates that $4 billion in annual financing is needed to grow and maintain Africa’s transmission network in order to achieve reliable access to power for the hundreds of millions of Africans who lack access to electricity today. Yet finance for grid infrastructure remains scant.

Some of the GCC countries’ investments in Africa have indeed included grid transmission components, and these countries also contribute to international funds and organizations that support African infrastructure development, such as the Islamic Development Bank. The Abu Dhabi Fund for Development is financing the construction of a 220-kilovolt power line that stretches 167 km in Tanzania with $30 million and has financed the establishment of power grids in five rural areas in Kenya with around $10 million. The UAE is also collaborating on the construction of approximately 400 km of new transmission lines and associated infrastructure in Mozambique, enhancing the country’s grid capacity. Saudi Arabia has pledged funds through the Saudi Fund for Development for various infrastructure projects, including electricity transmission lines in countries like Egypt and Sudan, and a $20 million soft loan to Rwanda to construct medium- and low-voltage power lines and distribution transformers.

Still, these GCC investments prioritize countries with clear infrastructure plans. Egypt expanded its transmission capacity by 17.7% during the fiscal year 2020-2021. While Morocco and Egypt have examples of successful energy sector reforms, it is important that countries without the same level of infrastructure planning capacity—where marginal investments into infrastructure planning and development can have much higher impact—have access to new finance. The GCC can distinguish itself internationally and have a far greater impact on the development and energy trajectories on the continent by devoting a higher share of its financing toward transmission and grid buildout projects, and by doing so across a more diverse set of countries.

Beyond energy: Link projects to new industries

Second, GCC countries can further distinguish themselves by embedding energy project developments within systemic infrastructure and industrial development plans. For instance, investing in a generation project alongside a demand-side project, such as a new industrial facility or data centre, can provide stable offtake for the generation asset while creating a more secure development and growth opportunity for the country receiving investment. Investing directly in market development, and creating opportunities for countries from the GCC to expand their own capacities by entering new markets, can drastically enhance the value of these investments, both for the GCC and for recipient countries.

This model of investment is one that GCC has begun to trial. Emirati artificial intelligence innovator G42, alongside Microsoft, is developing a $1 billion geothermal-powered data center in Kenya, including a 100-megawatt facility with the potential to scale up to 1 gigawatt in the future. This sustainable data centre is envisioned as a system-wide investment that not only addresses the growing demand for data services and technological advancements in Africa but also contributes to job creation, skills development, and the digital transformation of Kenya’s economy and the East Africa region overall. Linking new generation capacity to new demand investment directly can help reduce investment risk and reduce needed associated infrastructure investment, while providing a project around which the local economy—and power market and system—can grow.

Geothermal energy

GCC countries can also expand their impact on the continent by diversifying the generation projects that they finance. One with massive potential is geothermal—especially as advanced geothermal technologies such as superhot rock energy mature—as it can provide firm, 24/7 power and heat that could enable industrial development. While variable renewable generation projects require significant land area and infrastructure to store and/or transport energy to consumers, advanced geothermal can be extremely land efficient and co-located with major consumers, reducing associated infrastructure costs. There are major geothermal resources across much of the continent, and a history of geothermal success in countries like Kenya, where nearly half of power production is geothermal. Libya, Egypt, Algeria, Sudan, Chad, Niger, Ethiopia, and Nigeria are some of the African countries with the highest potential of advanced geothermal capacity that would benefit most from funding into this technology.

A modest handful of geothermal agreements were recently signed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, with investments made by Masdar and TAQA into the technology. Saudi Arabia has significant geothermal potential and an opportunity to be a global leader; Aramco is well positioned to champion advanced geothermal locally and abroad due to its expertise in drilling and the technical areas needed to deploy geothermal energy swiftly. Saudi Arabia recently established TAQA Geothermal Energy as a joint venture between the Saudi Industrialization and Energy Services Company and Reykjavik Geothermal after research has shown the kingdom to be rich in geothermal resources; the new venture will explore and develop geothermal resources in Saudi Arabia and the wider MENA region, which could open the door for further deployment in the African continent.

UAE’s Masdar has also invested in one of the world’s largest geothermal players, Indonesia’s Pertamina Geothermal Energy. Together they have announced a strategic partnership with the Geothermal development company to develop the Suswa geothermal field in Kenya with an investment value of $1.2 billion, aiming to develop 300 MW of geothermal power by 2030.

Other opportunities

GCC countries have several other opportunities to leverage their industrial expertise and comparative advantages to lead transformational investment in Africa. These include methane emission abatement, nuclear energy deployment, and critical minerals development:

- Methane: The climate case for investing in methane abatement is clear, as the gas has 80 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period and often can be profitable. Addressing methane leaks can thus deliver faster climate benefits than almost any other mitigation investment, including renewable deployment.And while investing in methane controls does not add power capacity, it can help create more efficient natural gas systems and generate returns far more readily than pure carbon abatement.

In 2023, only 2% of global climate financing was directed towards methane abatement, with sub-Saharan Africa receiving only 6% of these allocations. In 2020, methane emissions in Africa, excluding livestock, totalled 4.7 million tonnes, equivalent to 160 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions. Oil and gas was the highest emitting sector, accounting for 48% of those emissions. Egypt, Nigeria, and Algeria together generate over half of continental methane emissions.

The GCC has significant expertise and commitments in methane abatement: UAE and Saudi Arabia have set and are on track to reach 2030 net-zero methane targets. Saudi Aramco reported that its upstream methane intensity declined to approximately 0.04% in 2024, down from 0.05 % in the prior year. ADNOC is already collaborating with other national and international oil companies on methane reduction through global initiatives such as the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (OGMP) and the World Bank’s Global Flaring and Methane Reduction Partnership, providing a ready platform for extending methane expertise to African NOCs.

Several African producers are showing growing readiness for methane abatement, reflecting regulatory reforms as in Nigeria, participation in OGMP 2.0 by NOCs, and emerging integration of methane management into upstream policy frameworks. GCC NOCs would do well teaming up with those of Algeria, Nigeria, Libya, Angola, and others to provide financial and technical support, and assistance with policies and regulations to reduce methane emissions from oil and gas. This would avoid significant emissions while increasing fuel supply efficiency and providing African NOCs with an advantage in international markets, given anticipated new stringent methane intensity requirements from European importers. And methane abatement investment yields many non-environmental benefits, as they are relatively low cost and generate rapid returns through fuel recovery co-benefits. - Nuclear Energy: The successful venture of the UAE into nuclear energy for electricity generation in partnership with South Korea opens an opportunity to partner on the deployment of this technology in embarking and re-embarking countries, with lessons learned from the Barakah power plant – one of the few plants in the world delivered in recent years on time and on budget. That experience of successfully deploying a first nuclear plant in the country—which now supplies 25% of the country’s electricity needs—uniquely positions the UAE to support emerging economies in starting their own nuclear programs. In May 2024, ENEC and KEPCO signed an MoU to bolster research and investment opportunities in nuclear energy in third countries with the establishment of nuclear energy plants globally. For African nations with nuclear ambitions, the UAE may make an ideal partner on the finance, policy, regulatory, and construction expertise necessary to establish or expand their own nuclear energy programs. It is worth noting that multiple African countries have joined the global pledge to triple nuclear energy by 2050 that was launched at COP28 in Dubai. These include Ghana, Morocco, Kenya, Nigeria, and most recently Rwanda and Senegal.

- Mining and Critical Minerals: The African continent possesses significant reserves of the critical minerals and metals that are driving the global energy transition, including about half of the global supply of both cobalt and manganese. Currently, China is by far the largest buyer of and investor in African critical minerals. And despite the large reserves of critical minerals in Africa, the continent’s share of refining capacity globally is negligible; the materials are extracted in Africa and exported to be refined elsewhere. GCC countries could help African countries develop these resources and capacities in the higher value-added pieces of their value chains, including mineral refining. Doing so could create a lucrative new industry for GCC industry to partner with, while also lessening the geopolitical risks of market concentration in mineral refinement.

Saudi Arabia is poised to emerge as a prominent regional and global hub for green minerals processing. The Kingdom has already purchased a 10% stake in Vale SA’s base metals division in a $2.6 billion deal and announced that it would purchase $15 billion in global mining stakes to secure minerals from countries such as Namibia, Guinea, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In October 2024, Saudi Arabia’s Manara Minerals, a joint venture between Ma’aden and PIF, entered advanced discussions to acquire a $1.5–2 billion minority stake in First Quantum Minerals’ Zambian copper and nickel assets. The UAE has also signed a $1.9 billion deal with a state-owned mining company in the Democratic Republic of Congo to develop at least four industrial mines in the country. Further investment in refining capacity can help differentiate the GCC from other minerals investors and strengthen its partnerships on the continent, while also enabling much deeper development impact.

The GCC can play a key role in diversifying the kinds of projects that receive international financing in Africa. Enabling infrastructure, such as transmission and grid buildout, and clean firm power technologies will be critical to creating a reliable, sustainable, and universal energy system on the continent.

Transmission and distribution infrastructure has received far less funding—from the GCC and from major international development and financial institutions—than renewable power generation, perhaps in part because it can be more difficult to classify these projects as advancing ‘climate’ or ‘clean energy.’ But they could be far more transformational in reducing investment risk and enabling the rapid and successful deployment of clean energy.

Conclusion

The role of GCC countries in Africa’s finance landscape has been evolving rapidly. The UAE has become the leading investor in the continent: between 2019-2023 the UAE committed $110 billion in Africa, surpassing China as the largest bilateral investor on the continent. In 2022 and 2023, the UAE pledged $97 billion in new African investments — three times more than China, and now, Saudi Arabia is beginning to take up a similar role. Qatar has also started making considerable investments into renewable projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, and its entry signals a diversification of Gulf actors in African clean energy, complementing the more established portfolios of the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

The GCC’s investments can have a major impact on the energy transition finance opportunities on the African continent and influence the geopolitical conditions in the region. Achieving that level of impact will require the GCC to depart from the patterns of legacy development institutions, by structuring finance across the continent to target the highest impact projects, rather than those that bear the lowest risk. This means funding projects in countries beyond those that have been repeat beneficiaries of development funding in the past, and funding projects beyond renewable power generation alone. The GCC countries have the appetite to create their own pattern, moving beyond the traditional lower risk strategies that have stalled in achieving a holistic and sustained development while advancing the energy transition.

With the United States reducing its role in African development finance and Europe increasingly prioritizing its own energy security, the GCC has an opportunity to plug emerging gaps and chart a new path for international energy development finance in Africa. Creating closer partnerships with the neighbouring region can also offer GCC countries economic and diplomatic security as uncertainties abound in global markets and geopolitics.

African nations are walking a path that few countries have ever walked. While developed regions turned to climate after achieving significant levels of development—and near universal energy access—Africa is responding to climate change while simultaneously attempting to lift millions out of poverty and build out the region’s energy system. This balancing act calls for pragmatism and a full awareness of the opportunities and trade-offs between energy, development, and climate action in Africa.

Policy and regulatory changes in other regions will also continue to add new challenges and opportunities for African countries. With the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) regulation entering force in 2026, carbon-intensive exports will be penalized, and there is growing pressure on African industries to decarbonize if they want to maintain access to EU markets. In that context, investments from GCC countries could play a strategic role by financing cleaner power generation and enabling infrastructure—as well as industrial projects—helping African producers reduce their carbon footprint and remain competitive under CBAM rules.

As the GCC looks to usher in a new era as a global clean industrial hub, supporting partnerships can proliferate across the African continent, powering local value chains with a portfolio of clean energy technologies and shifting Africa’s current position as a source of raw materials to a bustling green industrial hub, while achieving significant cost efficiencies and generating tens of billions of dollars in additional revenue per year for the continent. For these partnerships to achieve maximum and durable impact—and spur further partnerships for GCC countries across the continent—they must create real value in destination countries, whether through ownership stakes or local workforce participation and upskilling. It is important to ensure mutual benefits across the two regions, harnessing shared opportunities that African and GCC countries can leverage to achieve more just and prosperous energy and climate futures.

By partnering and investing in clean energy projects across the global south, the GCC can not only address energy poverty but also foster mutually beneficial development opportunities. Such collaborative partnerships and investments can enhance energy security, promote technology transfer, and stimulate economic growth in both the GCC and recipient countries. GCC countries have already recognized this opportunity, investing tens of billions of US dollars into energy projects in Africa. By championing sustainable development initiatives on a global scale, the GCC is cementing its position as a forward-thinking leader in shaping the energy landscape of the future, thereby developing new economic opportunities and strengthening its geopolitical relationships with African countries. The GCC’s engagement in Africa will be most transformative if it evolves from capital deployment to partnership-driven co-development, ensuring that investments deliver clean energy, shared growth, and lasting local value.

1 Data on major projects was collected from public resources and databases, including from development funding reports, memoranda of understanding, and project announcements. While not all of these announcements are expected to reach financial close, the data provides valuable insight into the direction of future investments. This data also incorporates previous analyses, as noted, and is not intended to be exhaustive or capture every investment, but rather to demonstrate the key trends in and focuses of funding. Further, trends and pathways forward for investment were discussed with regional experts and stakeholders in bilateral meetings as well as in a roundtable discussion alongside regional stakeholders.

2 For projects without a monetary value specified, an investment of $1 billion per GW renewable energy was assumed based upon similar announcements. For green hydrogen, we doubled the figure to $2 billion per GW, and for offshore wind we estimated $4 billion per GW.