Recalibrating UK hydrogen towards a demand-led, systems-based approach

Author:

- Phil Cohen – Director, Hydrogen, Europe

The 2021 UK Hydrogen Strategy helped stimulate early industry momentum, but ambition has outpaced credible demand and policy coherence. Continuing with the current trajectory risks high public costs, limited emissions reductions, and missed opportunities to build a replicable, exportable model.

Hydrogen Allocation Round (HAR) 3 and the forthcoming Hydrogen Strategy update offer an opportunity to reset. By focusing on demand creation, replicability, and integration with the broader energy transition, the UK can ensure low-carbon hydrogen plays a meaningful role in reaching net zero – without being asked to do more than it can deliver.

Misaligned targets

The UK’s ambition for 10 GW of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030 has been essential in generating momentum within the industry. However, hydrogen’s potential role in national-level decarbonisation has subsequently diminished due to:

- A target misaligned with demand: The production ambition, initially set at 5 GW in the 2021 Strategy, was projected to supply an estimated 42 TWh of hydrogen by 2030. A year later, ambition was doubled to 10 GW, yet the Government’s official demand analysis for 2030 suggested a maximum demand of 38 TWh. Many sectors featured in the analysis are unlikely ever to use hydrogen in significant quantities, leaving it unclear where this additional hydrogen is intended to be used.

- Shrinking baseline demand: The 2021 Strategy referenced historical demand of up to 27 TWh, primarily for ammonia production and refining. With the closure of the UK’s two major ammonia plants (Ince and Billingham), hydrogen demand forecasts have decreased significantly.

- Miscalculated production cost: 2021 government analysis estimated the levelised cost of hydrogen (LCOH) at £110/MWh1, while the weighted average strike price awarded for HAR1 (2023) was £241/MWh2, resulting in an unexpected cost gap. This required higher than expected funding levels to fill and has limited viable business cases.

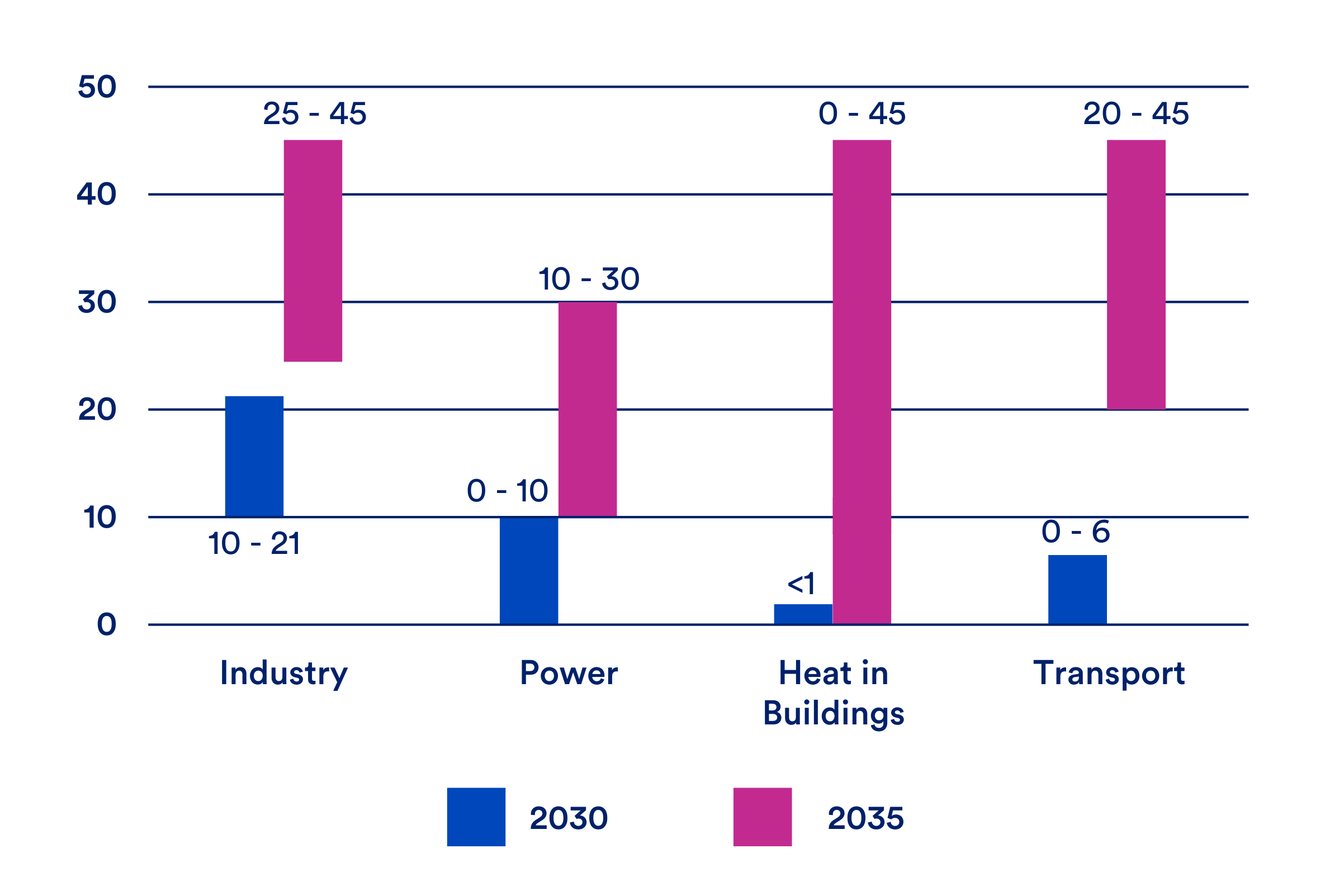

Figure 1. UK Government’s hydrogen demand forecasts for 2030 and 2035.

Source: UK Hydrogen Strategy (2021), Chapter 2.4: Use of Hydrogen

By focusing on production ambition rather than demand, the UK risks creating subsidised hydrogen without an end user. As signalled in the Government’s recent blending consultation3, this could lead to situations in which the hydrogen produced is discharged into the gas grid as the user of last resort. This is an inefficient use of public funds that ultimately undermines investor confidence.

The UK Government therefore need to harness the opportunity to strategically reframe hydrogen deployment, based on the following principles:

Prioritise a sectoral demand approach

A successful strategy update must focus on deploying hydrogen where it adds the most value and where there are no credible alternatives. Support should encompass both existing and new hydrogen demand.

Industrial decarbonisation

Industry is the primary user of hydrogen in the UK, with refineries demanding 70% of the 14 TWh of hydrogen produced today4. The Government will need to determine how far electrification can go to decarbonise industrial processes and where barriers arise, deploy low-carbon hydrogen strategically in sectors and processes that maximise overall industrial emissions reductions. A distinction must be made between large, geographically concentrated clusters and smaller, dispersed sites.

- Clusters: Due to its existing use as a critical feedstock in refining and chemicals production, low-carbon hydrogen’s primary role should be to decarbonise existing processes within industrial clusters where shared infrastructure can be developed. Whilst there is some uncertainty about the future of these industrial sites, targeted government support should focus here.

- Dispersed sites: Industries found in more dispersed locations account for approximately 50% of the UK’s industrial emissions. Whilst electrification will be the more sensible decarbonisation pathway for most sites, barriers exist, including limited technology availability and funding disparities compared to those for low-carbon hydrogen. Ceramics and glass production will likely be reliant in part on hydrogen to enable their decarbonisation5.

- Steel: Improvements in steel recycling should be prioritised to further reduce the need for primary steel production. However, where primary steelmaking remains necessary, hydrogen-based Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) offers a leading decarbonisation pathway but would create substantial hydrogen demand, so it should be integrated within broader cluster decarbonisation strategies.

- Low-carbon fuels: Decarbonised fuels, required for decarbonising the aviation and maritime sectors, will require large volumes of low-carbon hydrogen feedstock. The associated electricity demand will be significant, and the current Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation (RTFO) and sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) mandate rules exclude the use of low-carbon hydrogen produced with carbon capture and storage (CCS), limiting production flexibility in meeting this demand. With ammonia likely to emerge as a key maritime fuel, the UK could transform its mothballed ammonia plants into low-carbon fuel producers, particularly as they are located within planned CO2 transport and storage clusters. This will be a missed opportunity if exclusions on low-carbon hydrogen use for fuels are not lifted.

Transport, power, and heat

- Surface transport: There will likely be limited demand in niche applications, such as certain long-distance heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), however battery-electric vehicles will dominate in most markets.

- Power: Low-carbon hydrogen from natural gas with CCS could provide a dispatchable, low-carbon power source as an alternative to gas with post-combustion CCS. However, electrolytic hydrogen’s role will likely be marginal, limited to long-duration energy storage.

- Domestic heat: Hydrogen for domestic heating is no longer a viable pathway in the UK, a conclusion reinforced by several independent studies6 and the challenges faced by the Hydrogen Towns programme.

Recommendations:

- Shift the strategic approach from production-led to demand-led targets that emphasise a regional focus to create demand clusters with targets for emissions savings across industrial sectors.

- Integrate the Hydrogen Strategy into the broader UK Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy and prioritise low-carbon hydrogen production for industrial sectors where limited or no other decarbonisation options exist.

- Align industrial electrification and hydrogen business models and integrate this planning into the National Energy System Operator’s (NESO) Strategic Spatial Energy Planning (SSEP) for Great Britain, expected for publication in 2026.

- Allow all low-carbon hydrogen production pathways as eligible for low-carbon fuels production – limiting to only renewable production risks regulatory inconsistency, market confusion, and inefficient investment.

Update standards for market confidence

A hydrogen market must have a robust and pragmatic regulatory framework to function effectively. The current Low Carbon Hydrogen Standard (LCHS) is among the strictest rules globally for what constitutes low-carbon hydrogen. However, upstream emissions figures are based on default emission factors that can underestimate actual upstream methane emissions.

Without using real-time measured upstream emissions data, hydrogen produced using high methane-intensive gas could qualify under LCHS, thereby disincentivising future emissions reductions. The current rules, therefore, risk undermining the credibility of low-carbon hydrogen production, so they should be strengthened to support upstream and midstream natural gas emissions reductions.

Further, the current temporal correlation regulations of electrolytic hydrogen production are complex and could risk significant uncertainty for low-carbon hydrogen price forecasting, which in turn risks driving up project and subsidy costs. These strict requirements will become progressively less necessary as the Government moves closer to achieving its 2030 clean power ambition.

Recommendations:

- Strengthen upstream emissions rules to use measurement-based quantification, ensuring only gas that meets international methane intensity thresholds (such as is proposed in the EU Methane Regulation7) is used to produce low-carbon hydrogen.

- Relax temporal correlation rules initially to avoid electrolytic hydrogen market development delays, increasing ambition in line with grid decarbonisation.

Realign public funding and support mechanisms

The current funding landscape requires urgent review to ensure it drives innovation and cost reduction rather than simply subsidising operational costs.

While the UK cluster sequencing process correctly supports the deployment of low-carbon hydrogen with CCS in industrial clusters, the HAR process does not support projects aimed at decarbonising existing hydrogen demand nor where carbon-intensive hydrogen is currently used as a feedstock. This is a missed opportunity, as it is one of the few applications where hydrogen is already essential and commercially viable.

While successful at getting clean hydrogen projects started, the HAR model is expensive and has focused on small-scale projects; there are significant economies of scale that can be realised if the scheme targets larger projects, aggregating end users within close proximity. It also fails to enable replicability and does not align effectively with the government’s emphasis on electrifying industry wherever possible, as it provides subsidies to hydrogen projects not available to other decarbonisation pathways.

Further, recent reductions in targeted innovation funding and the decision to end the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund (IETF), which accelerated the utilisation of hydrogen in the UK, are a significant blow to stimulating hydrogen demand and wider industrial decarbonisation. The IETF, whilst constrained by its separation from HAR funding, played a crucial role in enabling the industrial use of hydrogen. HAR also focused on supporting technologies at or above Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 7, so it does not inherently incentivise innovations needed to make hydrogen cheaper in the long term. Removing innovation funding will ultimately weaken the UK’s ability to support earlier TRL technologies (TRL 4-7) that could dramatically lower the future cost of both hydrogen production and broader industrial decarbonisation efforts.

Recommendations:

- Redesign HAR 3 funding to support the full chain of a hydrogen project covering production, distribution, and use and tighten its focus on deployment in priority industrial applications.

- Establish new innovation funding streams that target TRL 4-7 hydrogen technologies and enable a wider array of industrial electrification options.

- Recalibrate industrial decarbonisation funding to prioritise an emissions reduction focus, creating a more level playing field between different decarbonisation options.

Building a resilient and credible hydrogen market

Low-carbon hydrogen is essential for decarbonising the UK; however, the current strategy and subsidy support mechanism, whilst enabling some clean hydrogen projects to develop, is expensive and lacks focus. A credible hydrogen market requires a shift from headline capacity targets to value-driven deployment. This requires a focus on:

- Demand-first strategy: Focus on hydrogen where it is essential, in industrial clusters and for sustainable fuels production.

- System integration: Align hydrogen policy with broader energy system planning, industrial decarbonisation strategies, and electricity system reinforcement.

- Credible standards: Establish clear, enforceable standards across industrial and transport demand for clean hydrogen while avoiding unnecessarily rigid compliance frameworks.

- Innovation and replicability: Rebuild the innovation pipeline, prioritise replicable projects, and avoid subsidising marginal use cases.

Footnotes

- See page 29: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/611b710e8fa8f53dc994e59d/Hydrogen_Production_Costs_2021.pdf

- See: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hydrogen-production-business-model-net-zero-hydrogen-fund-shortlisted-projects/hydrogen-production-business-model-net-zero-hydrogen-fund-har1-successful-projects

- Consultation: Hydrogen blending into the GB gas transmission network (July 2025): https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/hydrogen-blending-into-the-gb-gas-transmission-network

- DESNZ (2025) Energy Trends: September 2025: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/energy-trends-september-2025-special-feature-article-hydrogen-production-and-demand-in-the-uk-2022-to-2024

- DESNZ (2023) Industry of the Future Programme: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/findings-of-the-industry-of-future-programme

- Rosenow (2022): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542435122004160

- See: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1787/oj/eng

Credits

Author:

- Phil Cohen – Director, Hydrogen, Europe