Policy Silos: The Disconnect Between Climate and Development Agendas in African Countries

Prudence Dato, Michael Dioha, Boris Houenou, Brian Mukhaya, Lily Odarno, Michael Adu Okyere

Background

The 2015 Paris Agreement aims to keep global temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. As part of this agreement, countries committed to developing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to articulate their efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions and build resilient and adaptive systems to address the impacts of climate change.

Meanwhile, African countries continue to face significant socio-economic challenges. The continent has over 600 million and 950 million people without access to electricity and clean cooking fuels, respectively; 72% of the global population living in extreme poverty; 21 countries either at high risk or in debt distress; and a youth population projected to grow from 1.5 billion in 2023 to 2.5 billion in 2050 with constrained economic futures. To address these and other development issues, countries have developed National Development Plans (NDPs) to serve as strategic blueprints for promoting economic development, reducing poverty, and ensuring broad-based social transformation.

Since Africa faces the dual challenge of achieving development while addressing climate change, NDCs and NDPs should be mutually reinforcing, making their alignment vital for efficient resource allocation and investment. However, this alignment has not been systematically tested. With the ongoing update of NDCs under the Paris Agreement, it is important to verify the degree of alignment or misalignment between the two instruments to inform policy coherence and guide future planning. This study therefore assesses the extent of (mis)alignment between priorities articulated in African countries’ NDCs and development priorities outlined in their NDPs. It draws on a systematic content analysis of 52 NDCs and 98 NDPs from 52 African countries spanning 2000 to 2023.

Key Finding: African Development and Climate Plans Have Significant Priority Divergence

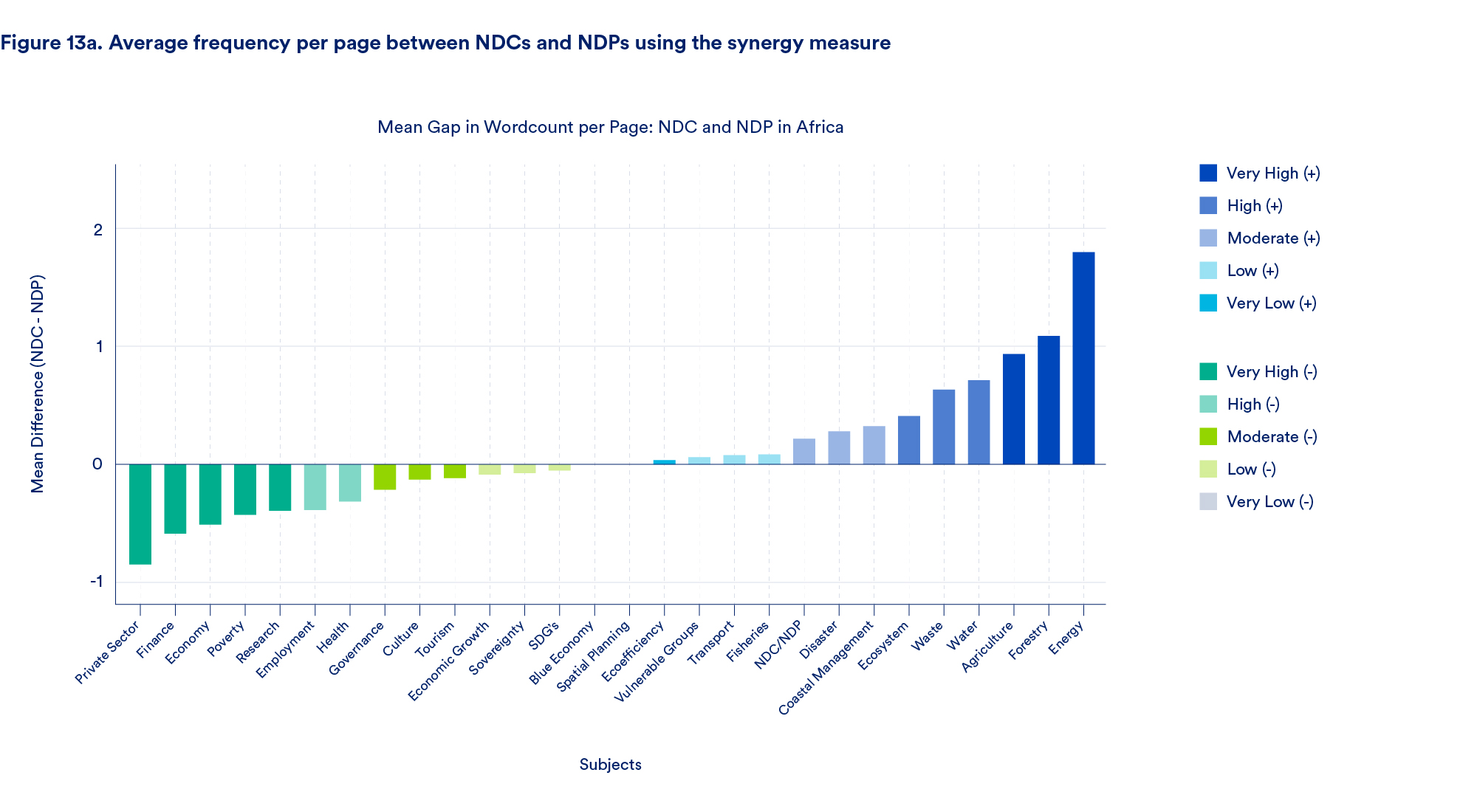

We find significant misalignments between the two frameworks across countries, various regional, income, and fragility groups. These findings suggest that most African countries maintain parallel rather than integrated climate and development policy frameworks. While NDCs focus on climate-related sectors like energy and agriculture, issues such as poverty, employment, and governance receive limited attention, whereas NDPs prioritize development themes with limited climate content. This split undermines both frameworks and bears real costs. For example, energy systems which are viewed as critical factors for effective climate action are also fundamental inputs in the structural transformation of African economies. By failing to capture this sector adequately in NDPs, the trade-offs between energy transition targets articulated in NDCs and the energy requirements for Africa’s economic transformation can be neglected, leading to energy transition strategies that lack pragmatism and work against, rather than for economic development. Moreover, if energy is relegated primarily to climate policy, the main indicators of sectoral “success” will likely focus on emissions reduction rather than on metrics more critical to economic performance, such as reliability, affordability, and access.

These divergences are deeply rooted in how each framework is formulated. NDCs are largely shaped by international financing and technical assistance, with environment ministries and global partners leading their design, while NDPs are domestically coordinated and dominated by economic planning ministries that emphasize growth and employment. As a result, NDCs often reflect externally driven climate agendas, and NDPs embody domestic development priorities, two parallel policy systems rarely designed to converge. This institutional and procedural divide weakens coherence between climate and development planning, limiting Africa’s ability to advance low-carbon growth in an integrated and nationally owned manner.

Additional findings from the analysis include:

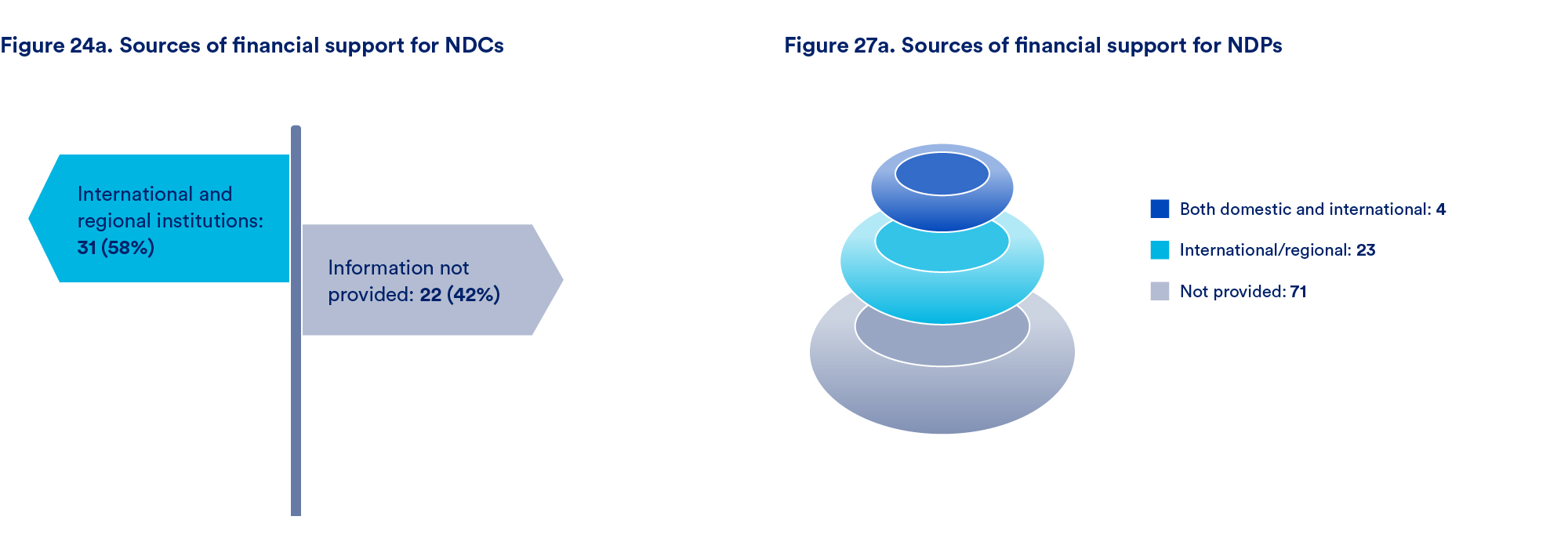

1. Funding and technical support for both NDCs and NDPs is predominantly provided by international partners and regional institutions.

Over half of the NDCs reviewed (58%) explicitly cite funding from international institutions (e.g., World Bank, UNDP, etc.) or regional institutions (African Development Bank (AfDB) and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)), while 42% do not specify their funding source. In sharp contrast, contributions from local institutions remain minimal, underscoring the strong external orientation of NDC funding flows and highlighting the dependency of African climate planning on international assistance. Iinternational and regional institutions provide the bulk of funding NDPs (23%), yet transparency is limited as 72% of NDPs provide no information on funding sources.

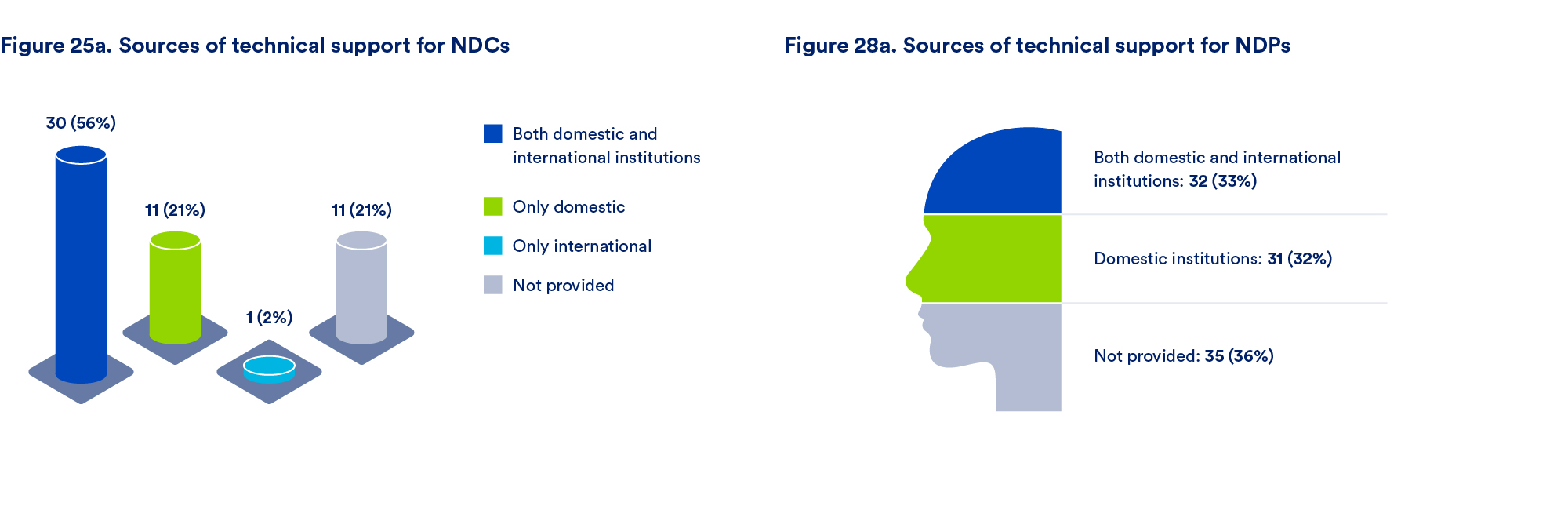

The majority of NDCs (56%) report technical contributions from both international and domestic actors, while only 21% including countries such as Zambia and Algeria rely solely on domestic institutions. This reflects the broader tendency for national actors to act as co-implementers rather than primary drivers of climate action planning. This dependence helps explain why climate-related themes, such as energy, feature prominently in NDCs, and why NDCs are often framed as externally oriented climate commitments rather than domestically embedded development strategies. Technical support for NDPs is more evenly split between domestic and international institutions, as 32% of NDPs are developed by domestic institutions, 33% of NDPs are developed by both domestic and international institutions, while the remaining 36% of NDPS do not provide information.

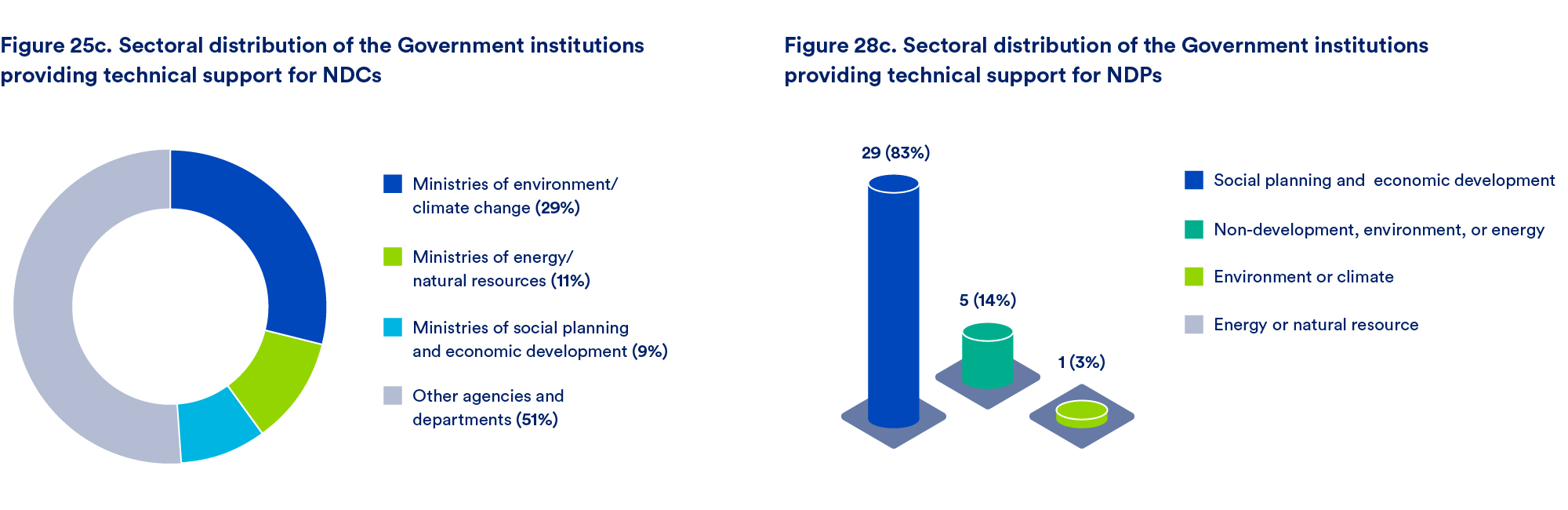

On the national side, governments’ part in providing technical support for the development of NDCs is uneven: of the 35 institutions identified, 29% are ministries of environment or climate change, 11% are ministries of energy or natural resources, and 9% are ministries of economic planning and social development, while the remaining 51% represent other ministries not directly related to development, environment, or energy. This distribution underscores how environmental and climate institutions dominate technical inputs for NDCs, with economic planning ministries playing more limited roles.

Regarding NDPs, the distribution highlights a strong dominance of ministries of economic planning and social development, which account for 83% of the 35 institutions, while representation from environment or climate ministries is minimal (3%), and energy or natural resource ministries are entirely absent. This indicates that domestic institutions, mainly ministries of economic planning and social development, play a somewhat stronger role in shaping NDPs than in NDCs, though international partners remain highly influential. It is therefore unsurprising that development-oriented themes such as finance, the private sector, and transport dominate NDPs, as these subjects align closely with the priorities of ministries of economic planning and social development.

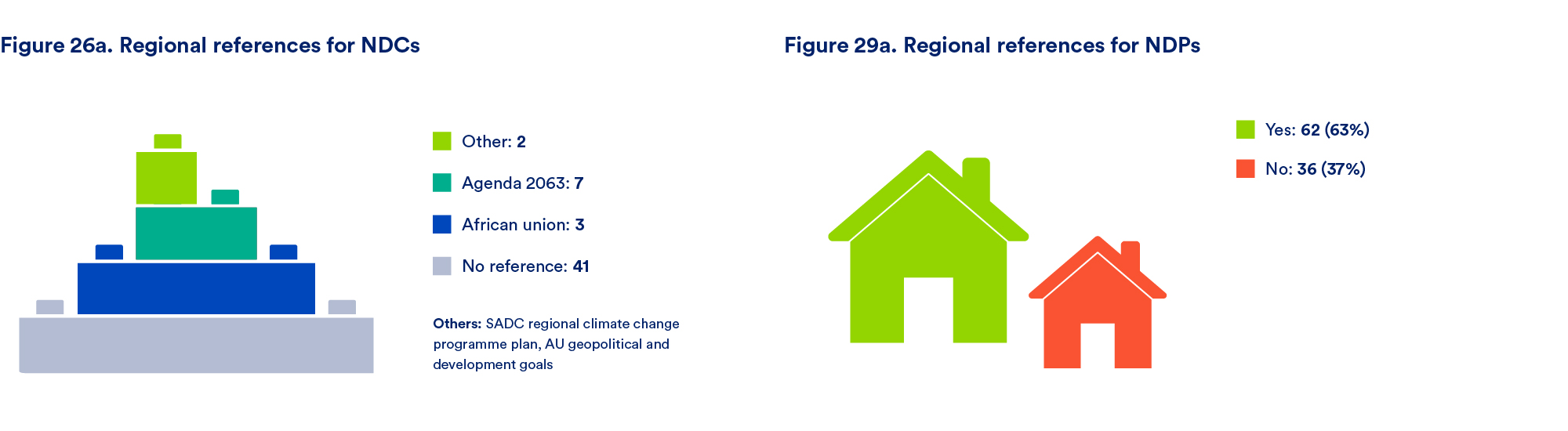

2. NDCs are largely disconnected from regional plans compared to NDPs.

Only 17% of NDCs refer to regional frameworks, with most of these citing the Africa Union (AU) Agenda 2063. The limited engagement of regional institutions and the lack of strong coordination mechanisms restrict the translation of continental or subregional priorities into climate pledges. This weak regional anchoring further explains the difficulty of integrating climate goals into broader development agendas. Unlike NDCs, most NDPs (63%) explicitly reference regional plans, with AU Agenda 2063 being the most common, while subregional economic communities such as ECOWAS, Southern African Development Community (SADC), and EAC are only sporadically mentioned. This stronger regional anchoring helps explain why development themes are more consistently embedded in NDPs than climate themes, and the prominent role of regional institutions. Development planning is explicitly tied to continental visions of economic transformation, whereas climate commitments remain less integrated.

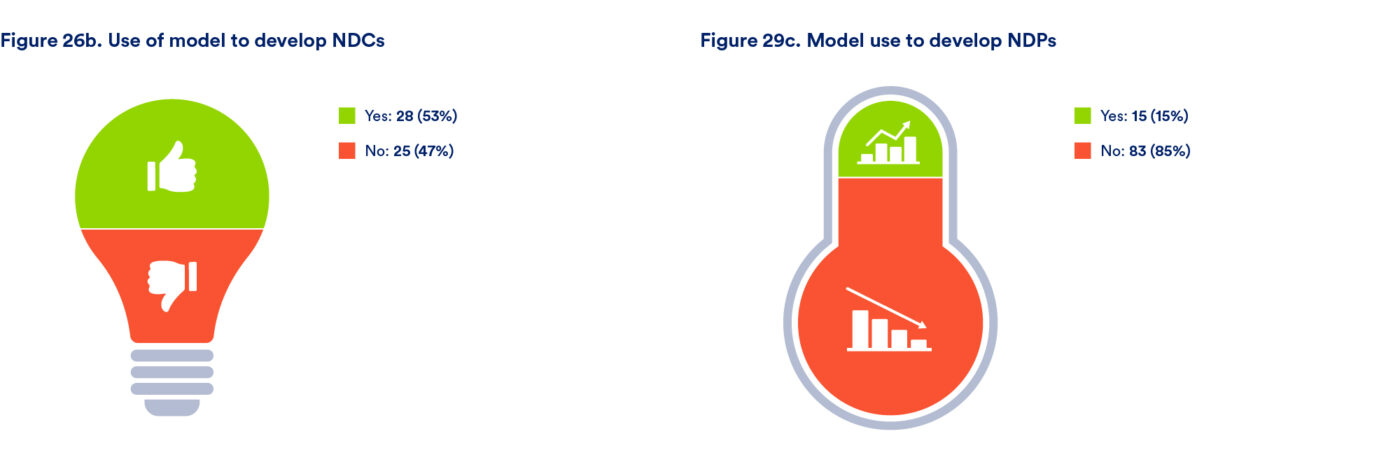

3. The use of sector-specific models in the design of climate and development strategies limit opportunities for integration.

Beyond reliance on UNFCCC guidelines, more than half of the African NDCs have declared the use of a specific modeling tool to inform their preparation, reflecting an effort to ground targets in analytical tools and evidence-based scenarios. This uneven adoption underscores persistent capacity gaps and highlights the differentiated quality of NDC formulation across the continent. In contrast to NDCs, very few African NDPs articulate the modeling frameworks employed in their development, with only 15% explicitly referencing the use of such tools. The infrequent use—or explicit non-mention—of modeling in NDP preparation underscores methodological diversity, partial disclosure of preparation methods, and a continued reliance on qualitative or consultative approaches, contrasting with the more standardized, model-drive processes that shape many NDCs.

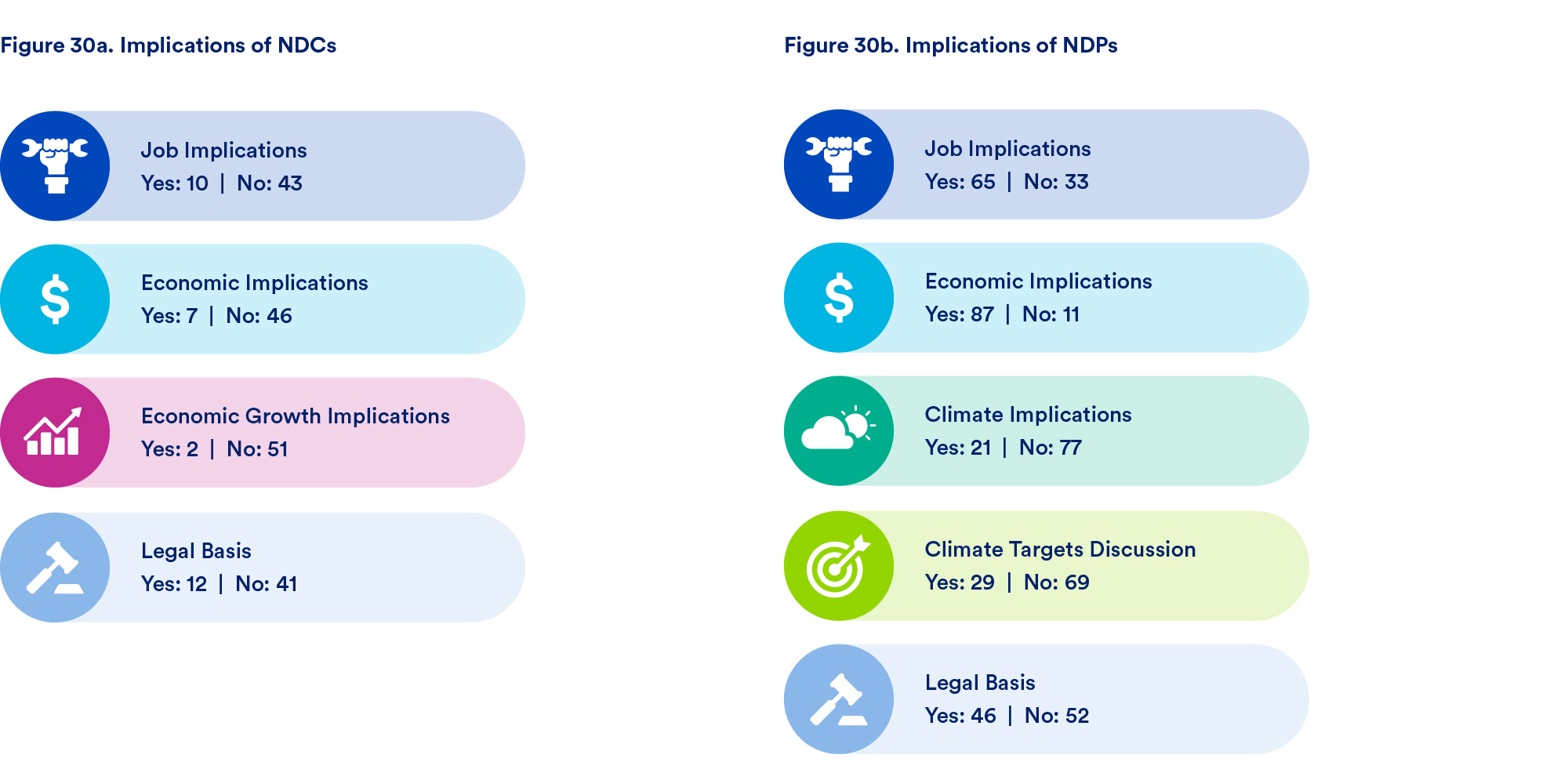

4. NDCs and NDPs prioritize different impact/success metrics

Regarding NDCs, the limited attention to jobs, economic growth, and national legal frameworks illustrates why they often remain disconnected from the central priorities of national development. Only a small minority specify job implications (19%), economic impacts (13%), or GDP-related factors (4%), and fewer than a quarter reference a national legal framework (23%). This narrow framing reinforces their role as externally oriented commitments rather than integrated strategies that respond directly to domestic socio-economic and institutional challenges. Without explicit links to national priorities, NDCs struggle to secure broad ownership, leaving their implementation vulnerable to shifting political agendas and resource constraints.

By contrast, NDPs articulate socio-economic implications more clearly, with the majority of NDPs addressing job creation (66%) and economic transformation (89%), while climate-related implications remain peripheral: only 21% of NDPs include explicit CO₂ or GHG reduction targets, and many of these draw directly from NDCs rather than being embedded within the development plan itself. As a result, while NDPs strongly shape budgets, investments, and institutions, they risk overlooking climate risks and failing to mobilize resources for mitigation and adaptation.

Steps Towards Coherent Climate-Development Strategies

As African countries grapple with escalating climate-related pressures while simultaneously pursing rapid economic development, it is crucial for countries to identify the trade-offs and synergies between climate action and development priorities and incorporate these trade-offs and synergies into their NDCs and NDPs. When countries align these frameworks, they can potentially access pooled financing from both climate and development funds, reduce conflicts between energy access goals and emissions targets, and ensure climate investments actively drive job creation and poverty reduction. To that end:

- African policymakers should prioritize closer alignment between development priorities and climate planning, especially across key sectors that serve as foundational inputs for economic growth, poverty reduction, and resilience. Institutional coordination and locally driven planning are mandatory to ensure full consideration of the specific local contexts. While these integrated frameworks will certainly pose greater governance challenges, African governments should establish permanent inter-ministerial committees, with representation from environment, finance, planning, energy, and sector ministries, to jointly develop, review, and reduce contradictory goals between both NDCs and NDPs.

- Stakeholders must view climate change planning within the framework of development and poverty alleviation imperatives. Most African countries face fundamentally different circumstances than wealthy nations in other regions. Given Africa has contributed merely 3% of historical emissions, together with its high levels of poverty, any framework should consider this context and prioritize development. NDCs must maximize development outcomes, with emissions reduction targets scaled appropriately to each country’s development stage.

- Countries should mobilize a diverse pool of financial resources to address their development and climate priorities. African countries need over three trillion dollars to implement NDCs and even more for NDPs. While closer integration between development and climate planning might enable governments to identify and pursue international co-financing opportunities, countries should recognize that this will be nowhere near the resources needed. Governments urgently need to mobilize a diversified pool of resources, including domestic capital markets, foreign direct investments, and international bond markets. African countries can unlock domestic capital by expanding and digitizing fair taxation systems; enforcing strong transparency and governance practices (such as open contracting, beneficial ownership disclosure, improving liquidity through competitive and well-regulated banking and brokerage sectors, and e-procurement); exploring multi-country collaborative methods for managing foreign exchange risk; and addressing illicit financial flows.

- African countries should collaborate on opportunities that accelerate growth while reducing emissions. Regional economic organizations (such as the East Africa Community, South African Development Community, etc.) alongside continent-wide initiatives, such as the African Union’s African Continental Free Trade Area, offer platforms for developing and sharing technical capabilities in the highest impact sectors, promoting cross-border integrated planning, reducing redundancies, and increasing access to development financing that could enable economic growth and emissions reductions. Meanwhile, regional financing institutions, such as the African Development Bank, should emphasize a focus on development priorities as a key criterion for funding of NDC-related projects.

- African governments, the private sector, and international partners should invest significant resources in building human resources on the continent that is vital for bridging the climate-development divide. Many African governments lack the technical expertise for integrated policy modeling, data systems for monitoring alignment, and institutional frameworks for coordinating across ministries. International support should prioritize building local capacity through training programs, regional knowledge hubs, and partnerships with African universities and research institutions. Rather than relying indefinitely on external consultants, support should catalyze the development of domestic expertise that enables long-term, locally driven planning rooted in African contexts and priorities.

- International development organizations, which participated extensively in the creation of existing frameworks, must reform how they set priorities to better integrate climate and development policies, especially in sectors critical for economic growth and resilience. The Paris Agreement’s NDCs framework should be structured to align with, rather than operate separately from, national development strategies. Since most NDCs and NDPs receive technical and financial assistance from international institutions, these institutions bear significant responsibility for current incoherence. Critically, wealthy developed countries must honor their historical responsibility for the majority of global emissions by substantially increasing climate finance to enable African countries to pursue both development and climate goals without being forced to choose between them.

What does the future look like?

The misalignment between NDCs and NDPs across Africa represents a fundamental challenge to the continent’s development trajectory. African countries, already saddled with significant debt, high unemployment levels, significant threats from effects of climate change, and underdeveloped infrastructure, cannot afford to waste resources on fragmented planning and deployment of scarce resources uneconomically. This study shows that the frameworks for development and emissions reduction are divergent in many countries, creating a risk that neither climate goals nor development objectives will be achieved if they continue operating on separate tracks.

The path forward requires recognition of trade-offs and strategic investment in opportunities with co-benefits for both objectives. For instance, development of energy can be an important driver of economic transformation and can reduce long-term emissions; agricultural modernization can enhance food security, build climate resilience, and reduce deforestation; and well-planned public infrastructure investments can drive economic growth while simultaneously enabling people to adapt to the effects of climate change.

The stakes are significant for African countries. Continued fragmentary planning and policies that do not address the socio-economic needs of African nations will doom them to continued poverty while not enabling them to meet any meaningful long-term emissions targets.