CATF Recommendations for the Upcoming Grid Package

- 1.1. Coordinate national and EU grid planning cycles.

- 1.2. Harmonise EU-wide and National system planning.

- 1.3. Enhance Siloed Sector Planning with Additional Economy-Wide Analysis.

- 1.4. Extending network development planning horizons from 10 to 20 years.

- 1.5. Improving the EU framework on Needs Assessments.

- 2.1. Establish national one-stop shops for network permitting and for facilitating project reviews.

- 2.2. Speed up permitting procedures.

- 2.3. Work towards the full digitalisation of permitting and review processes.

- 2.4. For CO2 projects, encourage the advance preparation of storage permit applications alongside exploration licence work programmes.

Introduction

Europe’s climate, economic, and competitiveness agendas all depend on a reliable, affordable, and decarbonised power system. At the centre of this system lies the EU electricity grid: stretching over one million kilometres, it is the most extensive and integrated network in the world, and a critical enabler of Europe’s energy transition. Yet today, Europe’s electricity grid is struggling to keep pace with the scale and urgency of the transition, particularly in the face of growing demands on the grid from electrification and data centre growth, and aging legacy generators that need replacement. Investment remains insufficient not only in clean generation and interconnections, but also in flexible and firm capacity needed to balance weather-dependent renewables and ensure security of supply. At the same time, the grid itself is not adequately prepared for the increasing physical risks of climate change, which threaten infrastructure resilience. These challenges are magnified by institutional and procedural bottlenecks. Lengthy and complex permitting procedures delay project delivery; fragmented and uncoordinated grid planning at the national and EU level hinders efficient grid development; and community opposition to projects and limited public acceptance for new infrastructure further slow deployment.

The upcoming European Grids Package, announced under the Action Plan for Affordable Energy, offers a timely opportunity to address these pressing challenges and deliver a more coordinated and forward-looking approach to Grid governance, planning and permitting. This brief identifies priority areas for the Commission where the package could deliver impact.

For further details, please see Compass Lexecon’s paper titled “Accelerating the Deployment of Clean Power Technologies to Reliably Decarbonise Europe through Enhanced Planning and Contracting Mechanisms”, commissioned by Clean Air Task Force.

Figure 1. Areas for Improvement for a Resilient Power System

CATF Recommendations for a Future-Proof Power System:

- Improve Planning. Ensure a more consistent planning framework at the national and European levels for the timely and cost-effective development of the electricity grid by:

- Coordinate national and EU grid planning cycles.

- Improve EU-wide system planning by establishing harmonised methodologies and aligning inputs, core scenarios, and sensitivities.Enhance siloed sector planning with additional economy-wide analysis.Extend network development planning horizons from 10 to 20 years.

- Improve the EU framework on Needs Assessments.

- Accelerate Permitting. Accelerate permitting with the following measures:

- Establish national one-stop shops for network permitting and for facilitating project reviews.

- Speed up permitting procedures.Work towards the full digitalisation of permitting and review processes.

- For CO2 projects, encourage the advance preparation of storage permit applications alongside exploration licence work programmes.

- Deploy Grid Enhancements. Support the modernisation of the grid and the deployment of grid enhancement technologies.

1. Consistent national and EU planning

1.1. Coordinate national and EU grid planning cycles.

What is the issue?

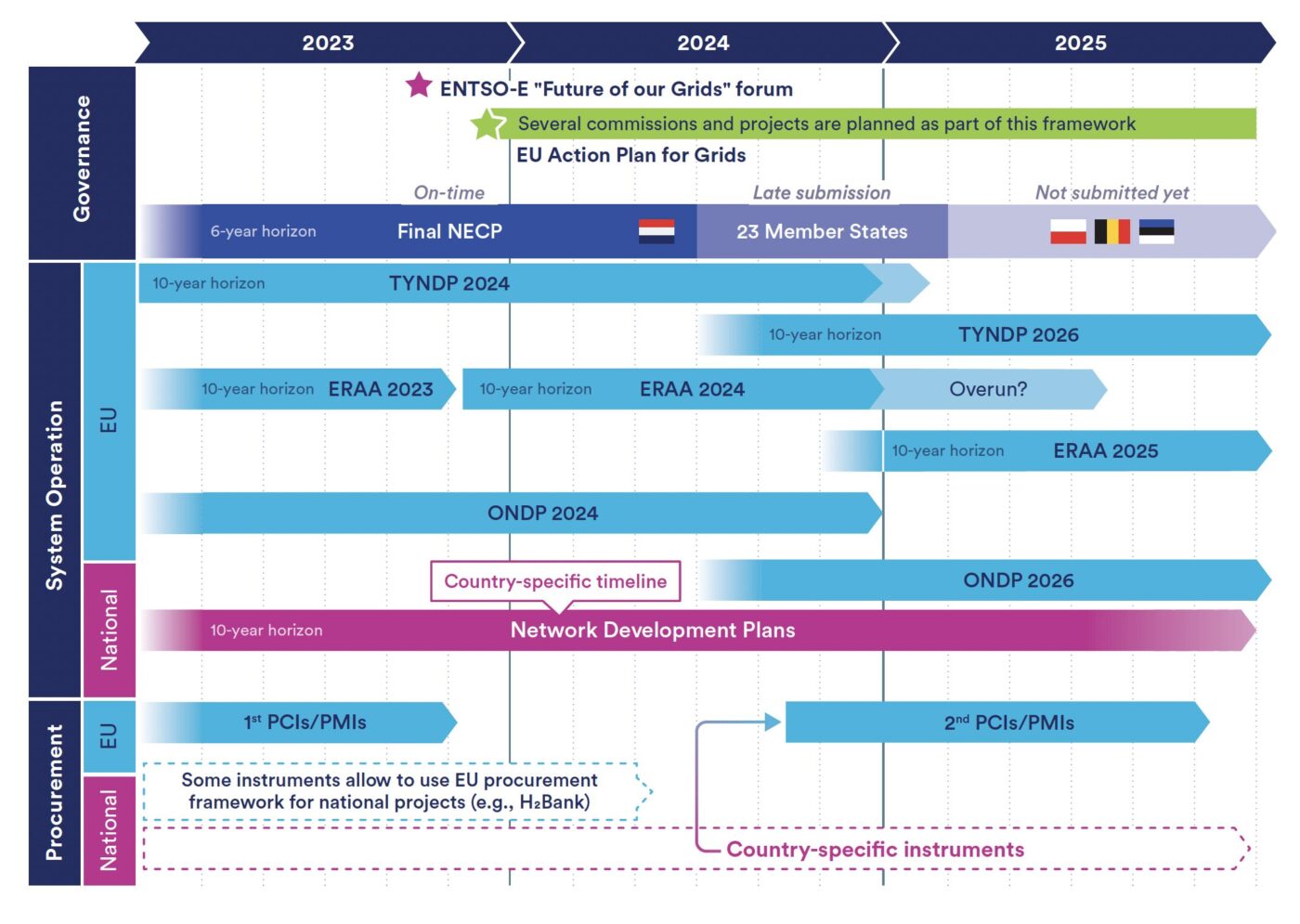

The current patchwork of planning mechanisms lacks a coordinated and comprehensive approach across the full value chain and the EU, regional, and national levels. Power system planning occurs across many layers, but often in silos—between sectors as well as between and within the Transmission System Operators (TSOs), Distribution System Operators (DSOs), regulators, and lawmakers. These processes are frequently misaligned, with differing planning cycles, methodologies, and levels of detail. Coordinating multiple plans across diverse governance levels and timelines is therefore highly challenging, hindering investment harmonisation and data comparability across the Union.1 These difficulties are further intensified by the limited public availability and accessibility of grid data.

Figure 2. A visual summary of system needs assessment in the EU.

Source: Compass Lexecon (2025). Accelerating the deployment of clean power technologies to reliably decarbonise Europe through enhanced planning and contracting mechanisms. Available here.

How can the EU solve it?

- Ensure coordination between national and EU planning cycles to prevent consistent misalignment.

- Align national and EU planning cycles on a two-year basis in line with ACER Opinion.

- Harmonise the planning cycles of Network Development Plans (NDPs) and the Ten-Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP), particularly for scenario building, needs identification, and cost-benefit analysis—to ensure consistent input data and more efficient grid planning and coordination.

- At the national level, strengthen cooperation between transmission and distribution system operators to ensure robust planning, and timely and targeted infrastructure development.

1.2. Harmonise EU-wide and National system planning.

What is the issue?

Given that there are several jurisdictional layers to electricity system planning, harmonisation in analysis and planning is a key gap in Europe. Aligning inputs, scenarios and sensitivities used in EU-level and national planning is urgently needed to improve EU-wide system planning. As an example, ENTSO-E and ENTSO-G results are heavily influenced by modelling assumptions about future scenarios—such as technology cost projections.

Several European Union bodies collect and publish data under different regulations. These institutions occasionally publish different data on what appears to be the same variable. Moreover, much energy modelling in Europe is performed with proprietary data and code. This results in a lack of transparency on how models arrive at final results, and reduces the possibility of stakeholder engagement. A recent publication by Bruegel titled “Europe’s energy information problem” outlines key gaps and proposes solutions.

In practice, an ideal approach would be for Member States to use consistent assumptions (noting that fuel prices, technology costs, financing costs, demand growth, and other metrics will still differ by Member State) and scenario frameworks across different planning processes, such that national plans and European outlooks accurately reflect a current and consistent outlook based on reliable data. To be clear, this would result in consistent assumptions across analyses, not the same values in all Member States.

EU guidance for scenario design will also need to be developed and Member States should justify deviations. A major challenge will be respecting national specifics, which will require data and assumptions to be segmented by Member State, while enforcing consistency across planning studies. Still, the current framework lacks any binding mechanisms to encourage consistency across EU and national planning.

How can the EU solve it?

- Develop a centralised EU energy data platform, publicly accessible, with a common2 reference point to inform energy system planning, network development and energy market design questions, but also long-term energy and climate scenarios, for consistency.

- Develop EU harmonised methodologies and core scenarios, updated on a regular basis, with a well-structured stakeholder process that ensures peer review and allows underlying assumptions to be challenged. This will ensure a common basis for planning, and coordination between the different parts of energy planning (infrastructure, gas, electricity, hydrogen and CCS) while taking into consideration flexibility for national and regional specificities.

- Ensure that Member States have to follow this harmonised basis and explain divergences and that they provide regular (every two years) updates on Member States’ national electricity sector decarbonisation progress and gaps, using these consistent methodologies.

- Identify and share best practices for electricity system planning and disseminate them among Member States.

- In the 2027 review of the TEN-E Regulation, ensure joint scenario-building by European networks that is informed by the harmonised scenarios and sensitivities.

1.3. Enhance Siloed Sector Planning with Additional Economy-Wide Analysis.

What is the issue?

Electricity sector planning is largely siloed to electricity-specific planning processes. While some non-electric sector consideration is accounted for via assumed electricity load forecasts, cross-sectoral analysis is limited at the EU-level. As such, electricity sector planning, and other sectoral planning, could be enhanced if EU economy- wide analysis was performed to identify synergies and interdependencies of various EU decarbonisation strategies across the economy.

How can the EU solve it?

- Develop an economy-wide analysis that includes the co-optimisation of electricity, natural gas, carbon capture, and hydrogen infrastructure to identify cross-sector synergies and infrastructure solutions that would not be captured in siloed analyses. This analysis should include technology breakthrough scenarios to help inform EU technology commercialisation funding (e.g. Horizon Europe). This will require aligning existing planning processes and timelines to result in well-timed coordination between European and national efforts, and mechanisms to evaluate and develop identified solutions.

- Expand ENTSO-E and ENSOG’s coordination (see latest electricity and hydrogen report) to other energy-related infrastructure, and create an electricity and gas coordination group with a clear mandate and responsibilities that includes stakeholders’ representatives. Such an approach would support efficient coordination between these plans and policies with adequate stakeholder engagement, aligned with the inputs developed in 1.2 above.

1.4. Extending network development planning horizons from 10 to 20 years.

What is the issue?

Because infrastructure planning and development has long lead times, and energy infrastructure assets have long lifespans, near-term decisions have long-term implications. Currently, many planning processes (e.g. ENTSO-E’s Ten-Year Network Plan,3 the European Resource Adequacy Assessment) have planning horizons that are only 10 years long, often representing only a quarter to half of the lifespan of the infrastructure and does not include decarbonisation target dates. Failure to look beyond 10-years also risks not capturing potential up-sizing opportunities for infrastructure, such as grids, to avoid having to expand capacity soon after the 10-year horizon.

How can the EU solve it?

To take advantage of proactive planning and economies of scale, all planning processes at the European and national levels (e.g. ENTSO-E Network Development Plan, NECPs, etc.) must extend need assessments (i.e. system analyses) and planning horizons to 20 years to capture long-term solutions and avoid piecemeal short- term approaches that do not align with long-term goals. This extension will ensure that infrastructure with long lead times (grids, storage, new renewables) and the trajectory toward climate neutrality are considered. While precise forecasts 20 years out are challenging, scenario planning can reveal trends and highlight the need for no-regrets investments (e.g., grid reinforcements).

To ensure a 20-years horizon in scenarios, the following measures will be needed:

- Electricity Regulation (EU) 2019/943 should be updated to extend the scope of the European resource adequacy assessment and TSO network development plans to 20 years ahead.

- In the next revision of the TEN-E Regulation, guidelines for TYNDP scenarios should include a 20-year scenario aligned with EU climate targets. This longer view would inform policy decisions like coal phase-out deadlines or offshore grid build-out well in advance. Require Member States to submit progress reports on their electricity market and grid progress every five years, with review to be done by the Commission.

1.5. Improving the EU framework on Needs Assessments.

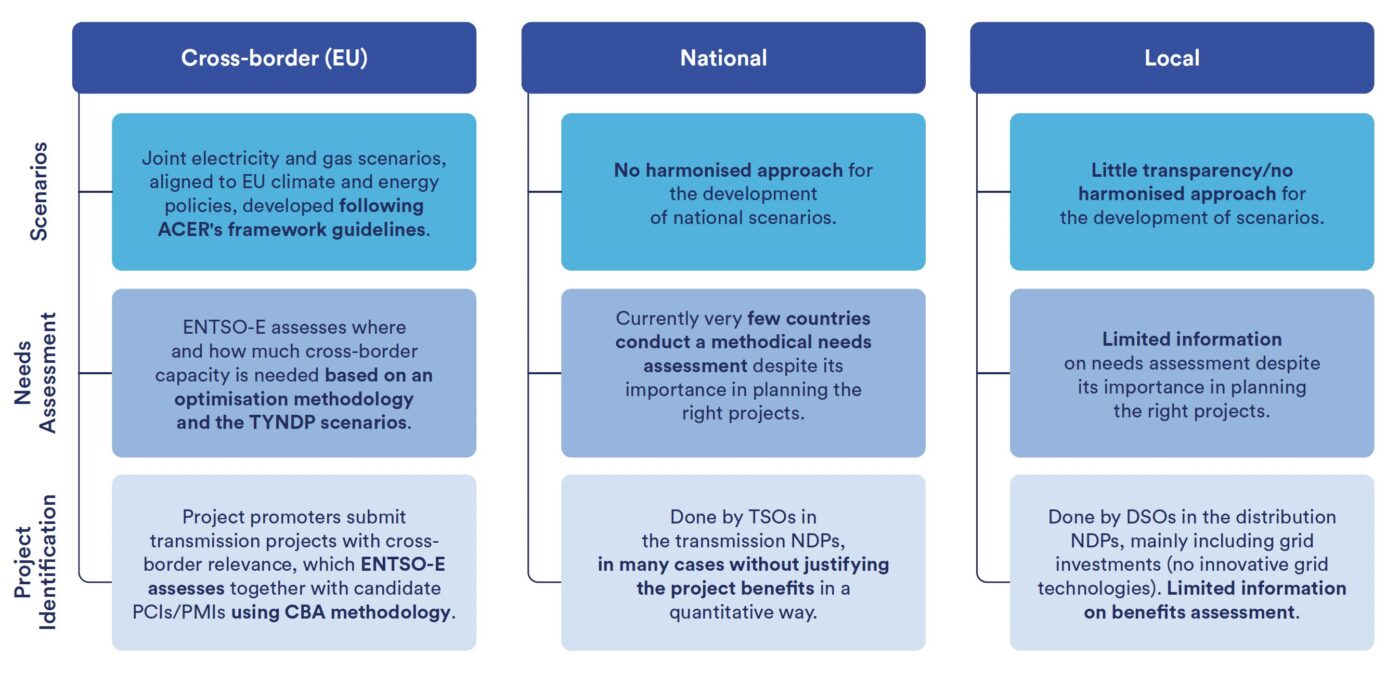

What is the issue?

System needs assessments are being developed thanks to positive changes brought by the Electricity Market Design (EMD) reform and a range of ongoing new planning initiatives across Europe. Still, the current framework at both

the European and national levels to assess system needs continues to be too narrow and short-term, solely focused on adequacy, flexibility, and network development. Also, the underlying methodologies do not adequately cover resilience issues, and misalignments persist in timing, methodology, and data between national and EU-level plans.

Figure 3. Network needs assessment on the European and national levels (ACER)

Source: ACER (2024) Electricity Infrastructure Monitoring Report, page 14.

The current set of overlapping system-needs-assessment mechanisms lacks a comprehensive framework to address gaps and recognise interdependencies and trade-offs. Responses to the 2024 TYNDP exercise on scenario building highlight missing inputs, such as energy efficiency gains, some hidden costs on hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, or constraints on raw material value chains.4 These examples denote a lack of comprehensiveness in how the current set of system-needs-assessment mechanisms addresses such real-world constraints and their transversal and cross-border effects on energy systems. According to the Draghi report, addressing system needs will lead to a reduction of costs of about EUR 9 billion/year in 2040, which far outweighs the cost of investing in Europe’s grid of EUR 6 billion/year for 2040.

How can the EU solve it?

Improve and unify Europe’s needs-assessment framework by:

- Improving the scope, quality, and coordination of system needs assessments to better ascertain needs in line with policy targets at the EU, regional, and national levels.

- Integrating the wide range of energy vectors and technologies under a unified system-needs-assessment framework, shifting from a single sector infrastructure needs assessment to a multi-sectoral planning framework, in line with the joint ACER and CEER position paper.

- Extending the scope of system needs assessments to cover any key hidden constraints, and the time horizon to 2050 to provide a clear long-term view and showcase the added value of long-term no-regret investments such as grid reinforcements.

- Widening the scope of electricity system needs assessment in EU legislation and going beyond the network expansion and capacity adequacy covered in ERAA and TYNDP, to also cover energy system resilience. In cooperation with ACER and ENTSO-E, develop formal guidelines for integrating adequacy, flexibility, and resiliency assessments.

- Monitoring progress in cooperation with ACER and ENTSO-E, and providing recommendations on integrating adequacy, flexibility, and resiliency assessments every two years.

- Ensuring the TYNDP follows a more top-down European approach to identify cross-border infrastructure needs and better linking identified needs and priority projects of European interest.

2. Accelerating Permitting

A comprehensive permitting reform will be crucial to deliver clarity and efficiency in processes, while avoiding duplicative efforts and safeguarding environmental protections of the existing EU framework.

2.1. Establish national one-stop shops for network permitting and for facilitating project reviews.

What is the issue?

Grid projects often involve multiple authorities and jurisdictions responsible for permitting and environmental review processes that must coordinate on, review, and approve plans. Sufficient administrative capacity to process permits and review documents is often lacking, and records and processes are often not digitalised, complicating transparency and efficiency efforts.

How can the EU solve it?

- Issue dedicated legislation on infrastructure permitting and establish a centralised one-stop-shop authority in each Member State responsible for processing permits and facilitating environmental reviews for energy infrastructure projects, similar to the TEN-E provisions for PCIs. These single points of contact should be responsible for interactions with grid network developers and regulators, improving certainty and clarity for all stakeholders.

- When considering introducing one-stop shops for network permitting, the EU should leverage and incorporate findings from both (1) national level implementation of one-stop-shops for PCIs/PMIs if and (2) one-stop shops for net-zero manufacturing technology projects as established via the Net Zero Industry Act.

2.2. Speed up permitting procedures.

What is the issue?

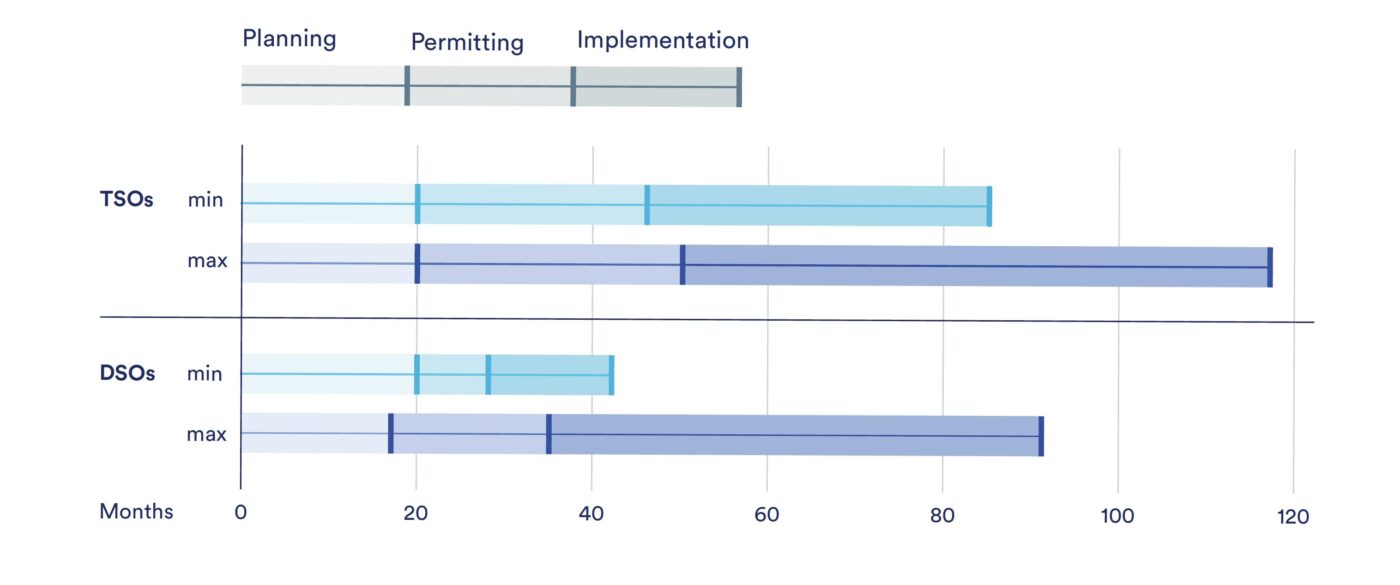

Overall, permitting accounts for about 25% of the total time needed for grid investments, and it continues to be one of the main causes of delay in project implementation.5

The EU has introduced several meaningful provisions for the acceleration of permitting procedures,6 and there are good examples of streamlined permitting and environmental assessments practices at the EU level, particularly for those cross-border projects that can benefit from priority status of projects on the Union list.7 For example, the revised TEN-E regulation lays out clear requirements for establishment of a one-stop-shop in Member States for permitting Projects of Common Interest (PCI), and once those shops are created, Members States must issue permits for these projects within 3.5 years. The TEN-E regulation also advises cooperation between Member States in “pre-application” processes for cross-border projects. EU environmental review legislation is also generally clear.

However, despite these EU frameworks, challenges remain. Regarding PCIs, only a limited number of projects make it onto the PCI list; therefore, few transmission network infrastructure projects can benefit from these provisions.

Additionally, slow transposition and inconsistent implementation at national and regional levels persist, and where projects cross borders, Member States are not required to coordinate to harmonise processes, slowing deployment.8,9

Figure 4. Planning and permitting: roughly half of the total time for grid infrastructure projects.

Source (ECA, 2025)

How can the EU solve it?

- Call on Member States to implement the streamlined permitting rules from the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) regarding the grid. Concretely, this includes on: Art. 16(f) on overriding public interest; Art 15(b) on mapping; Art. 15(c) on renewable acceleration areas and Art. 15(e) on areas for grid and storage infrastructure. In parallel, the Commission could consider building from the positive elements from the Emergency Regulation on permitting to streamline, simplify and accelerate permit-granting procedures.

- Facilitate open and clear channels of communication between designated permitting authorities in each Member State to collaborate on cross-border projects and work to harmonise national practices and policies, even if not explicitly required by EU law.

- Member States should heed best practices identified by the European Commission and conduct integrated environmental assessments that centralise all EU, national, and sub-national permits required and come to a single environmental review decision from an authorised decision-making authority.10 This would require a more streamlined implementation of existing laws in Member States.

- Specific to environmental assessments for PCIs, the EU can build upon its recommendation to Member States in the TEN-E regulation to cooperate on pre-application processes and provide guidance to Member States on such cross-border coordination. Improved clarity and expectations from Member States would benefit both project applicants and authorities in different jurisdictions. The European Commission found that some Member States, like Spain, have established a cross-border consultation process that engages other States potentially impacted by infrastructure and invites them to participate in environmental review processes.11 This could serve a good starting point for other Member States and, potentially, for the EU more broadly.

- Alleviate inadequate staffing and funding of permitting offices to accelerate permitting procedures. As more projects are proposed, more specialised staff will be required to process applications and liaise with other authorities.

2.3. Work towards the full digitalisation of permitting and review processes.

What is the issue?

Digitalisation of permitting and review processes allow for speedier document submission and review, better coordination among parties engaged in permitting, more transparency and clarity, and easier review and enforcement by authorities within or across Member States. However, today, permitting timelines are lengthened by insufficient digitalisation and a lack of digital tools to process complex applications efficiently.

Programs like the Technical Support Instrument provide support for permits and other activities categorised under “green transition,” but as more projects are permitted, more resources will be needed for digitalisation efforts.12 More extensive use of existing digitised resources and adoption of new and centralised online submission portals, tracking systems, and standardisation tools should be accelerated.

How can the EU solve it?

- The EU and Member States should collaborate to make up-to-date environmental and geological data relevant to the permitting process publicly available. This can speed permitting by providing a broader shared information base to incorporate into permits and environmental review documents.

- The EU should consider a revision to the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive, which has not been updated since 2014, to streamline digital requirements and integrate other improvements to and best practices for environmental review processes that have been developed over the past decade.

2.4. For CO2 projects, encourage the advance preparation of storage permit applications alongside exploration licence work programmes.

What is the issue?

Carbon capture and storage can face particularly challenging timelines for deployment, as many of the first wave of projects in the EU are required to also establish accompanying CO2 transport and storage infrastructure, including pipelines, terminals, and new geological storage sites. The burden of value chain coordination on industrial actors will decline over time as this infrastructure becomes more established, but it remains a significant cause for delay in project final investment decisions. While the Net-Zero Industry Act sets a time limit of 18 months for permitting Net-Zero Strategic Projects, including CO2 storage projects within this designation, the Commission should consider further steps to ensure this timeline can be realised in practice.

How can the EU solve it?

- The Commission should encourage the advance preparation of storage permit applications alongside exploration licence work programmes, via an ongoing and active dialogue with the competent authority.

3. Support the modernisation of the grid and the deployment of grid-enhancement technologies

What is the issue?

While new, greenfield infrastructure is needed to achieve climate and decarbonisation targets and ensure grid resilience, new infrastructure must be sited, permitted, approved, financed, and constructed. Under current practices this can take significant time. Simultaneously, a massive grid infrastructure already exists, and that infrastructure is in need of significant upgrades and modernisation. Implementation of “grid-enhancing technologies” on existing transmission and distribution infrastructure can both modernise systems and increase the efficiency of existing infrastructure, lessening the magnitude of new deployments needed and providing a cost- effective, quick-to-deploy option to improving grid capacity.13 These technologies – including dynamic line ratings, power flow controls, and advanced conductor technologies, among others – incorporate hardware and software upgrades to enhance grid capacity and flexibility. Integrating these technologies into existing grid infrastructure could increase overall network capacity by between 20 and 40%.14

How can the EU solve it?

Existing infrastructure is key to supporting fundamental grid operations and maintaining reliability and resiliency during the energy transition. Upgrading existing infrastructure can help reduce the overall cost of grid modernisation and expansion efforts. Member States should purposely upgrade existing grid infrastructure, integrating grid upgrades and efficiency-enhancing technologies more comprehensively into system level planning. The European Parliament briefing on EU electricity grids identifies grid enhancing technologies as a way to lower costs and reduce time to deploy while upgrading and modernising existing infrastructure, but notes that these technologies are not “systematically” considered by system operators and national regulatory authorities as solutions. Integrating these technologies will improve system efficiency at lower cost than new build and likely incur less review because key infrastructure is already sited in existing rights-of-way.

Footnotes

- European Court of Auditors. Review 01/2025: Making the EU Electricity Grid Fit for Net-Zero Emissions. European Court of Auditors, 2025.

- Ensuring quality and lasting trust requires a well-governed stakeholder process built on transparency—of models, data, and assumptions. Openness enables errors to be spotted, assumptions to be challenged, and constructive debate to take place. It also supports peer review, institutional learning, and independence from individual modellers, ensuring continuous improvement over time.

- Network development plans are the primary instruments for identifying infrastructure needs and setting investment priorities. At the national level, TSOs prepare network development plans (NDPs), while the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) produces the EU-wide Ten-Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP) to address cross-border infrastructure needs. The EU TYNDP is a major tool for coordinated and efficient network planning, but giving its non-binding nature, the TYNDP implementation strongly depends on NDPs.

- TYNDP 2024 scenario opinions: Eurelectric (2023) TYNDP 2024 Scenario Storyline Report. Available here. Bellona Europa (2023) TYNDP 2024 Scenarios Input Parameters. ACER (2024) Opinion No 05/2024. Available here.

- https://www.eca.europa.eu/ECAPublications/RV-2025-01/RV-2025-01_EN.pdf

- Directive (EU) 2023/2413 (Renewable Energy Directive – RED III), Directive (EU) 2024/1788 (Directive on Gas and Hydrogen Markets), Regulation (EU) 2022/869 (TEN-E Regulation), and Regulation (EU) 2024/1735 (Net-Zero Industry Act)

- Article 7, Regulation (EU) 2022/869

- https://www.solarpowereurope.org/press-releases/new-report-average-eu-member-state-transposition-of-permitting-rules-for-renewables-falls-short-at-just-under-50

- https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e62186f9-4b27-11f0-85ba-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e62186f9-4b27-11f0-85ba-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e62186f9-4b27-11f0-85ba-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- https://commission.europa.eu/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/technical-support-instrument/technical-support- instrument-tsi_en

- https://watt-transmission.org/what-are-grid-enhancing-technologies/

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/772854/EPRS_BRI(2025)772854_EN.pdf