How to accelerate emissions reductions in the agriculture sector? Put farmers at the center of methane action

Brazil is an agricultural powerhouse and has successfully increased food production and productivity over the past 50 years. In livestock production, Brazil boasts an impressive herd of 238.2 million cattle, exports 25% of its beef, making it the largest beef exporter in the world is also a significant producer of chicken and pork.

Against this backdrop, it’s no surprise that food systems featured prominently at COP30 in Belém late last year, the annual meeting of climate negotiators and other stakeholders. A key development was a growing consensus that reducing agricultural methane requires a farmer-centered approach — one that recognizes farmers and producers as the principal agents of change. Across government, industry, research institutions, and civil society, discussions converged on a shared reality: while the agriculture methane system involves many actors, action ultimately happens on the farm.

To translate global ambition into real emissions reductions, countries must understand this system and design policy and implementation strategies that support farmers rather than burden them. And as many at COP30 underscored, the most effective path forward is the development of context-specific, farmer-centered plans and policies that reconcile economic development, food production, and climate objectives. Policies can also unlock scaling and adoption of innovative methane-reducing technologies, creating market signals for public-private partnerships and investment in development of context-specific technologies. Therefore, targeted philanthropic investment in policy development, impact evaluation, and advocacy can play a critical role in turning scientific progress into real, sustained methane reductions.

Integrating agricultural development and methane mitigation is the key for reducing emissions

Agriculture is the largest source of human-made methane, and this methane comes primarily from the digestive process and manure of ruminant animals, particularly cattle. Cattle production is expected to increase globally due to an increasing global population and a greater demand for meat and milk.1,2,3 Consequently, methane emissions from livestock are also expected to increase by 10% by 2030, and by 21% by 2050 above 2020 levels, even accounting for the historical gains in productivity observed in key livestock producers since the 1960s.

Despite this, agricultural methane remains underrepresented in national climate strategies. Recent analysis from the Food and Agriculture Organization indicated that 85 national signatories of the Global Methane Pledge (GMP) have added measures that target agricultural methane as part of their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs). However, only 4% of these countries have established a quantifiable target for reducing their agricultural methane emissions, and none of these are aligned with the GMP’s timeframe or 2020 reference year.

Furthermore, out of the 28 countries responsible for 80% of agricultural methane emissions, only a third have policy instruments that can impact livestock emissions. Many countries reference livestock sustainability or agricultural productivity but do not connect these goals to methane targets. Others include methane in their NDCs but lack a sectoral plan for implementation.

The false tradeoff between agricultural development and methane mitigation

One reason agricultural methane has lagged in climate policy is the perception that reducing emissions will constrain production or impose undue burdens on farmers. But this framing rests on a false tradeoff. In reality, methane mitigation and agricultural development are closely linked.

Without climate action, sustainable productivity gains, farmer incomes, and livelihoods will erode, costing the sector billions by the end of the century. Climate change can alter rain patterns, undermining pasture production, quality, and availability in key cattle-producing regions in the world.4 These impacts reduce stocking rates, slow weight gain and production, impair animal health and reproduction, and increase heat stress and mortality, all of which can increase methane production. Because farmers’ livelihoods depend on stable environmental conditions, climate-driven disruptions risk devastating social and economic impacts.

Why farmer-centered approaches matter

Methane mitigation action that integrates agricultural development with a farmer-centric approach is key to accelerating emissions reductions and mitigating the above risks. Above all, it creates trust between the environmental community and the farmers who ultimately implement change on the ground.

Farmers are more likely to adopt new practices when they understand how technologies work, see clear benefits for farm management and labor. Adoption is further encouraged when new practices generate financial returns or market access, are accessible and affordable, help farmers adapt to climate stress, and are socially accepted within their communities.5,6

Countries can take action to support outcomes for climate and farmers

Because climate change and agriculture production are deeply intertwined, countries should integrate climate mitigation into livestock development policies. From the supply side, reducing methane emissions from livestock requires two parallel actions:

- productivity must sustainably increase at greater pace than historical gains, and

- new methane-reducing technologies and practices must be developed and incorporated into livestock production systems.

Effective policies to accelerate productivity gains and the adoption of methane-reducing innovations depend on a clear understanding of emissions sources, the economic and complementary drivers shaping farmer decisions, and robust systems to monitor progress. Yet today, only 13% of global methane emissions from all sectors are covered by policies, with agriculture being the least represented sector, with only 17% of these policies. While agriculture methane policies are increasing globally, they remain concentrated in Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region and focus primarily on manure management.

Although the technologies used by farmers will vary by geography, farm type, production system, the type of feed available, and many other context-specific factors, accelerating global action depends on changing farmers’ behavior. Policies play a central role in enabling the adoption of technologies and practices that will unlock productivity and income gains, reduce methane emissions, and adapt to a more challenging environment.

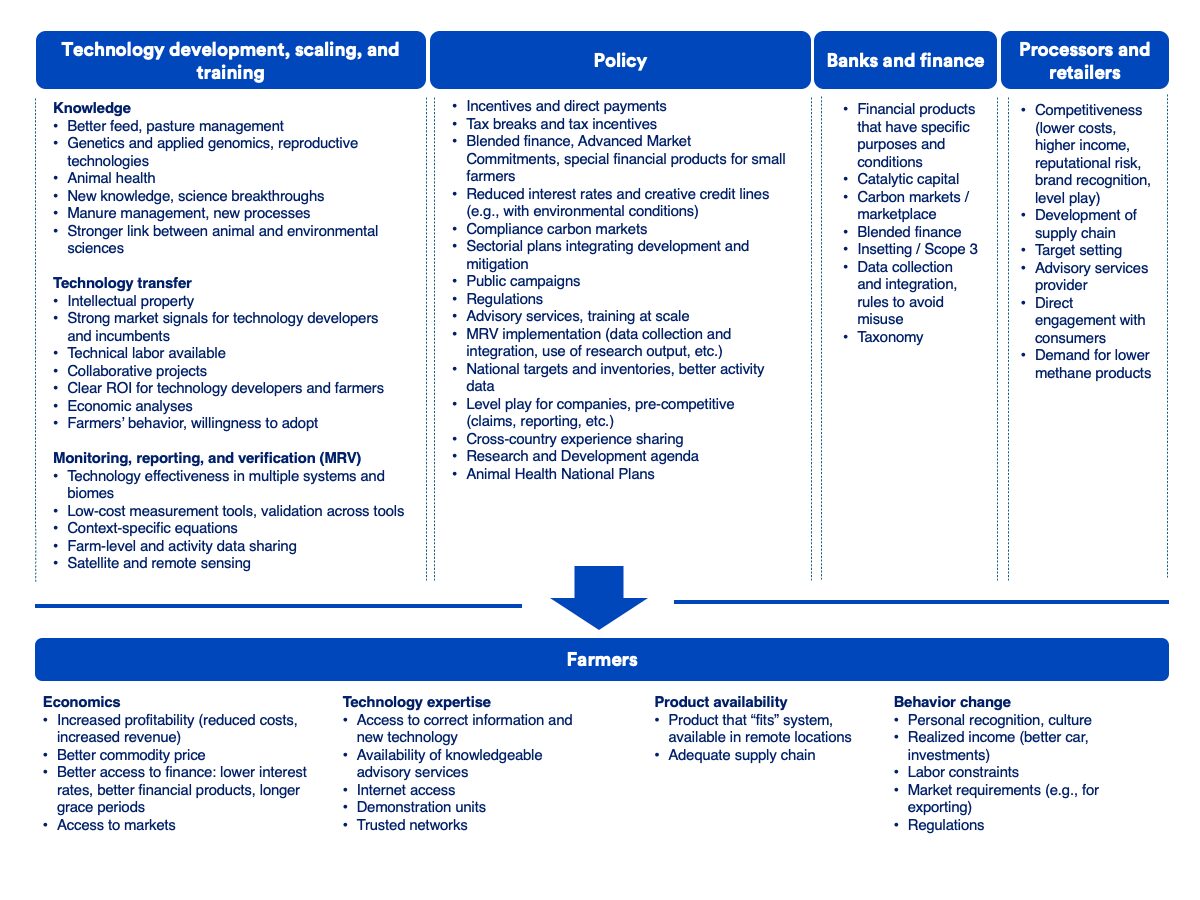

Methane action in the agricultural sector will likely come from a mix of policy instruments combining economic incentives, complementary measures, information sharing, and regulatory mechanisms. These policies can target farmers directly, as well as actors that interact with farmers, creating a chain of action that ultimately delivers methane reductions. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Non-exhaustive summary of points of intervention that must occur to accelerate action to reduce methane emissions from the livestock sector

Learning from existing models

Brazil’s Programa Mais Leite Saudável,7,8 offers a compelling example of how aligned incentives can drive change. The program allows dairy processors to receive tax credits when they invest in technical assistance for their farmers suppliers. Though not originally designed as an environmental program, it demonstrates the power of well-structured incentives to mobilize industry participation and shift farmer practices at scale.

Since 2015, more than 394,000 dairy farmers have benefited from over 2,000 projects across more than 1,000 municipalities, supported by governance and verification systems.9 It offers a model for future methane-focused initiatives and demonstrates that immediate action is possible when incentives and support systems are aligned.

At the same time, evidence on the economic and social impacts of policies that combine agricultural development with methane mitigation remains limited. Gaps in data on implementation costs and effectiveness, particularly in reducing methane emissions, constrain the development of innovative policy instruments. There is an urgent need for approaches that can simultaneously deliver methane mitigation, climate adaptation, and economic development.

Philanthropy and civil society can significantly drive agricultural methane policy forward

Philanthropy and civil society have played an important catalytic role in advancing global methane action, particularly seen through the establishment of the Global Methane Hub. Important tools such as CATF‘s Country Methane Abatement Tool, which we have used to support oil and gas emission analysis, policy development, and capacity building in a host of countries around the world were developed with support from philanthropic funds.

Philanthropy is also pushing innovation in the development of breakthrough solutions for reducing methane from livestock and rice. Agricultural policy is complex and context-specific; integrating development and environmental benefits, particularly methane mitigation, will require strong engagement between NGOs, governments, and agricultural stakeholders to design and develop policies that support continuous agricultural output growth, food security, and methane mitigation. Policy development and impact evaluation must happen at all levels to drive changes in farmers behavior (Figure 1). This collaborative, global effort can significantly benefit from the catalytic power of philanthropy. Supporting capacity building among policymakers and stakeholders, applied economics and social research, policy development, applied policy tools, and advocacy efforts are crucial for methane reductions in the agricultural sector to be obtained.

A “Plan to Accelerate” integrated action

In this context, CATF is co-leading the Plan to Accelerate (PAS) “Integrating Agricultural Development and Methane Mitigation” with the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). CATF’s leadership brings global experience in developing and advocating context-specific, science-based, pragmatic policies that lead to reduction in methane emissions. Hosted under the CCAC’s agricultural flagship Farmers’ Initiative for Resilient and Sustainable Transformations (FIRST), the PAS will serve as a platform to accelerate progress at the place where real action happens: the farm. In collaboration with multiple partners, our goal is to empower state and non-state actors, providing successful case studies and strategic information that can support policy development and advocacy that integrates agricultural development plans with methane mitigation action.

Conclusion

As the largest source of human-made methane emissions, agriculture needs to urgently accelerate action at the farm level through policies that integrate development and methane mitigation, aimed at multiple agricultural stakeholders. This can be achieved through pragmatic policy development and implementation. Furthermore, collaboration across actors working to reduce methane emissions from agricultural sources is a cornerstone of success, given the complexity and specificity of policies aimed at agriculture.

Importantly, improving the evidence base of the impact of policies in sustainably increasing productivity, income, and reducing emissions is crucial, and so is the collection of data that can support these analyses.

Funding applied research that develops the economic and social base for innovative policy mechanisms, evaluates the impacts of policy instruments, and expands practical and economically feasible monitoring, reporting, and verification tools is urgently needed. This evidence is critical to understanding how different policies mixes can create synergies or trade-offs between productivity and environmental outcomes. In addition, support for advocacy that engages state and non-state actors to build trust and drive action is essential.

1 OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/07/oecd-fao-agricultural-outlook-2025-2034_3eb15914/full-report/dairy-and-dairy-products_1dd2e5a6.html

2 Van Eenennaam, 2024. Addressing the 2050 demand for terrestrial animal source food. PNAS Vol. 121, e2319001121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.231900112

3 Our World in Data. Global meat consumption. World, 1961 to 2050. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-meat-projections-to-2050

4 Lee et al. (2017). Forage quality declines with rising temperatures, with implications for livestock production and methane emissions. Biogeosciences 14, 1403-1417. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/14/1403/2017/bg-14-1403-2017.html

5 Arbuckle Jr. et al. (2015). Understanding farmers’ perspectives on climate change adaptation and mitigation. Environmental Behavior 47: 205-234. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0013916513503832

6 Franz et al. (2025). Discontented agricultural transformation – why are farmers protesting in Germany? J. Rural Studies 120: 103837. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0743016725002785

7 Programa Mais Leite Saudavel – PMLS. https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/producao-animal/programa-mais-leite-saudavel

8 Agronegocio – entenda o credito presumido. https://azedoefranco.adv.br/entenda-o-credito-presumido-no-agronegocio/

9 Controladoria Geral da Uniao, Brasil, 2022. Relatorio numero 1154172: Avaliacao dos Programas Mais Leite Saudavel e Plano de Qualificacao dos Fornecedores de Leite. https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/producao-animal/programa-mais-leite-saudavel