Geologic Hydrogen in Context

Author:

Amy Ouyang, U.S. Associate, Hydrogen, Clean Air Task Force

Hydrogen is a critical feedstock that can help reduce greenhouse gas emissions in sectors that are difficult to electrify, such as heavy industry, heavy-duty trucking, maritime shipping, and aviation.

As the world moves to decarbonize hydrogen production, a lesser-known hydrogen source is beginning to draw serious attention: geologic hydrogen. Sometimes labeled “natural”, “white”, or “gold” hydrogen, this form of molecular hydrogen is generated underground through natural geological processes.

Long overlooked by policymakers and the energy sector, geologic hydrogen is gathering increasing interest from researchers, policy makers, industry, and climate advocates as a potentially low-cost, low-emissions source of hydrogen complementing more familiar low-carbon production pathways like electrolytic or fossil fuel-based hydrogen with carbon capture.

As interest in geologic hydrogen grows and early exploration efforts expand across the U.S., Europe, and beyond, it’s critical to understand the promise and limitations of geologic hydrogen. This document offers a high-level snapshot of the current state of knowledge to help inform future research, policy, and investment decisions.

What is geologic hydrogen?

Geologic hydrogen is molecular hydrogen that forms naturally underground through geological processes. Key natural formation mechanisms include:

- Serpentinization: A chemical reaction in which water interacts with iron-rich rocks, producing hydrogen gas.

- Radiolysis: The splitting of water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen due to natural radiation from radioactive elements in rocks.

- Other processes: Including microbial activity and the decomposition of organic matter.

Where can geologic hydrogen be found?

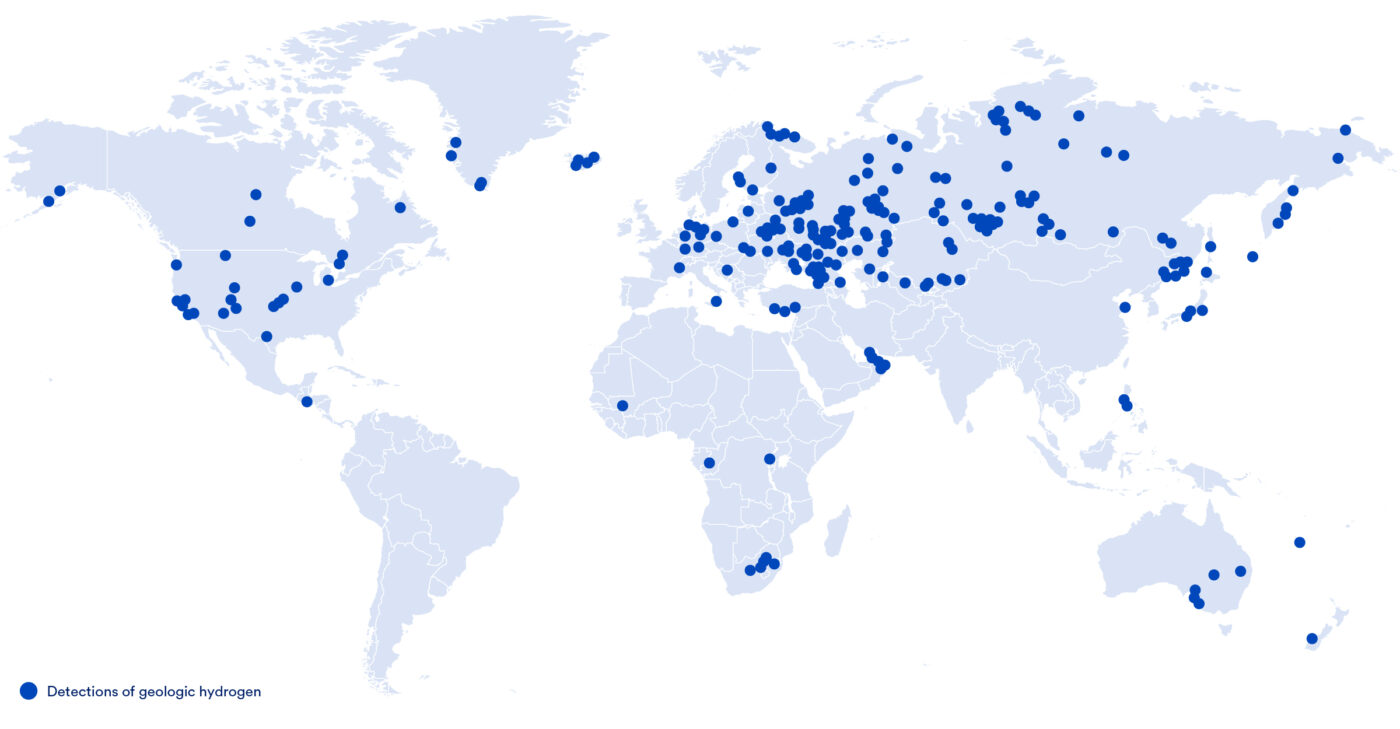

By late 2023, more than 50 companies globally were investing in natural hydrogen exploration, as per American Gas Assocation’s estimates. Figure 1 below highlights areas where recent research has indicated the possible presence of geologic hydrogen.

Figure 1: Possible Geologic Hydrogen Sites Worldwide (Source: New Scientist)

How can geologic hydrogen be extracted?

Three primary extraction pathways exist:

- Natural Accumulation: Hydrogen naturally generated through geological processes can accumulate in subsurface reservoirs, similar to hydrocarbons. Obtaining hydrogen from these reservoirs is the most mature method and has been demonstrated in limited-scale real-world settings. A notable example is the pilot-scale Bourakébougou field in Mali, where hydrogen has been extracted and utilized for small-scale electricity generation since the 1980s.

- Stimulated Accumulation: In cases where hydrogen is present in geologic formations but not freely flowing, techniques like hydraulic fracturing or electrical stimulation can help release it from the rock. These methods are still in early R&D stages and remain unproven at scale.

- Stimulated Generation: Hydrogen can also be produced underground by injecting water into reactive rocks to trigger hydrogen-generating reactions like serpentinization. This is the most speculative pathway and is currently being tested in small-scale pilots.

What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of extracting geologic hydrogen?

Advantages:

- Low carbon emissions: When extracted without co-produced hydrocarbons, geologic hydrogen theoretically has a near-zero carbon footprint. Where hydrogen content of the extracted gas is 85% and minimal methane contamination, the carbon intensity is around 0.4 kilogram of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per kilogram of hydrogen (H2). At 75% hydrogen and 22% methane, the intensity rises to 1.5 kg CO2e/kg H2.1 Geologic hydrogen’s theoretical low carbon intensity positions it well to meet the existing thresholds for clean hydrogen production.2

- Potentially abundant “renewable” energy source: Estimates suggest vast underground reserves of ~5-6.2 trillion tons of geologic hydrogen globally, even a small fraction of which could be sufficient to satisfy global hydrogen demand for hundreds of years. Unlike fossil fuels, which deplete on human timescales, studies suggest that in some cases the natural underground reactions that produce hydrogen can sustain themselves, meaning geologic hydrogen reservoirs could be replenished over time, though further research is needed to confirm the rate and reliability of this process.

- Cost-effectiveness: Geologic hydrogen has the potential to have lower production costs compared to other sources of low-carbon hydrogen, as the required inputs are comparatively less expensive. Where present, valuable co-products such as helium could be monetized, further improving project economics and diversifying revenue streams. The cost of geologic hydrogen extraction/production will also depend on the level of intervention required from extraction to deployment (i.e., hydrogen separation and purification from the gas mix composed of nitrogen, methane, and helium; hydrogen gas compression; and storage and transport infrastructure). But early evidence suggests it can theoretically be cheaper than other low-carbon hydrogen sources: for example, a small well in Mali is producing hydrogen at an estimated cost of only $0.50/kilogram of H2. Developers in Spain and Australia are similarly targeting ~$1/kilogram of H2 production costs.

Table 1: The production cost of different hydrogen production pathways

| Hydrogen Production Pathways | Production Cost ($/kilogram) |

| Unabated Fossil Fuel-Based Hydrogen | 0.98 – 2.93 |

| Electrolytic Hydrogen | 3.74 – 11.69 |

| Fossil Fuel-Based Hydrogen with CCS | 1.80 – 4.70 |

| Geologic Hydrogen3 | 0.50 – 1.00 |

- Leveraging existing expertise and infrastructure: The exploration and extraction of geologic hydrogen can leverage existing tools, technologies, and expertise from the oil and gas industry. Activities like drilling, subsurface mapping, and gas handling are already well-established, and techniques such as seismic imaging and well logging can be adapted for geologic hydrogen exploration.

Challenges:

- Resource uncertainty: Until recently, few scientists or companies had seriously explored underground hydrogen, resulting in sparse global data. While early findings are promising, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has cautioned that scaling up novel hydrogen sources, including geologic hydrogen, faces uncertainty given limited commercial experience, uneven geographic distribution, and the need for further validation through large-scale projects. The Mali project referenced above is the only active geologic hydrogen extraction site currently in operation. While it represents a significant milestone in demonstrating the technical viability of geologic hydrogen, its production is limited to just five tons per year, making it suitable only for small-scale electricity generation. This highlights the current uncertainty surrounding the scalability of geologic hydrogen as a viable energy resource.

- Need for further research, development (R&D) and demonstration projects: While naturally accumulated hydrogen has been proven to exist and flow in limited settings, most geologic hydrogen extraction pathways – including stimulated accumulation and generation – remain at the experimental or lab stage, and have not yet advanced to commercial-scale demonstration. To better understand their viability, significant investment in field trials, reservoir modeling, and surface detection methods is crucial.

- Infrastructure challenge: Geologic hydrogen deposits may not align with existing industrial demand centers, leading to a likely geographic mismatch between supply and demand. In the absence of co-location, delivering naturally accumulated hydrogen to end users could require substantial investment in new infrastructure, such as pipelines, storage, or transportation systems. These logistical and capital requirements may complicate project economics and delay deployment timelines, even where geologic hydrogen resources are otherwise promising.

- Extraction complexity: Exploratory drilling is expensive and uncertain; many wells may turn out to be dry or produce only trace amounts of hydrogen. These heightened early-stage risks could discourage investors, especially if initial projects underperform. Even when hydrogen is present, it may be trapped in deep or remote formations that are too costly or difficult to access. As of 2025, no commercial-scale extraction methods exist for geologic hydrogen, which increases uncertainty. Scientists are still learning which geological conditions favor hydrogen formation, how to spot them on the surface, and how these reservoirs behave over time. Hydrogen is a highly diffusive gas, and data is lacking on long-term well production rates. Until such knowledge matures, discovering and extracting hydrogen in commercially useful volumes will remain a significant barrier.

- Environmental impact: Natural hydrogen is rarely found in its pure form and is often co-located with gases like nitrogen, methane, or helium. Methane in particular raises climate concerns: if it’s released or flared during production, the resulting emissions could cancel out the environmental benefits of using geologic hydrogen. The need to treat these impurities adds to operational complexity and can significantly increase production costs. Likewise, any hydrogen that leaks during production or transport is an indirect greenhouse concern as it can extend the atmospheric lifetime of methane and influence stratospheric water vapor. Like other extractive industries, it may also face scrutiny over land use impacts, permitting, and public perception challenges, in a way similar to the oil and gas industry. These risks might warrant further research and monitoring as hydrogen infrastructure scales.

Looking ahead

Geologic hydrogen holds real promise as a potentially low-cost, low-emissions energy source, but significant research and demonstration are still needed to fully understand its viability, scalability, and environmental impacts. As interest grows, it is critical that development efforts are guided by science, transparency, and responsible practices. Stay tuned for more from CATF as we continue exploring this emerging area.