Africa’s energy future in a post-aid world

As development aid collapses, Africa’s energy future hangs in the balance—and the continent may be better for it.

- An energy sector at risk?

- 1. Expanding and rebalancing Africa’s energy finance ecosystem

- 2. Tackling Africa's electricity sector crisis

- 3. Treating energy investment as a development multiplier

- 4. Strengthening regional integration to drive industrial growth and energy resilience

- 5. Elevating an African agenda over external determinism

The world of global development has experienced seismic shifts in recent times. Several of Africa’s key bilateral funders — the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, the Netherlands and Sweden— have all announced significant cuts to development spending to make room for their own national priorities. These recent trends further deepen what had already been a steady decline in official development assistance to the developing world since 2020. Africa has seen the steepest decline with a 10% drop in ODA flows since 2020. In 2021 alone, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office cut aid to several Eastern African countries (a region considered a priority for the UK) by half or more.

As one of the biggest recipients of aid, Africa is taking a hard hit from these cuts. Seven of the eight poorest countries in the world, which are expected to see shortfalls of over 3% of GNI due to U.S. development aid cuts, are in Africa. These are Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Uganda and Ethiopia.

But many across the African continent see this so-called death of foreign aid as an important inflection point: one that can incentivize a long-overdue pivot from Africa’s chronic aid-dependency. In an address to regional leaders at the East Africa Global Health Security Summit in Mombasa, former president Uhuru Kenyatta called on African leaders to view aid cuts as a wake-up call to pursue self-reliance and better manage domestic resources.

This moment of reckoning poses a fundamental question: Can Africa seize this shift to forge an energy future built on its own terms, powered by domestic capital and driven by African leadership?

An energy sector at risk?

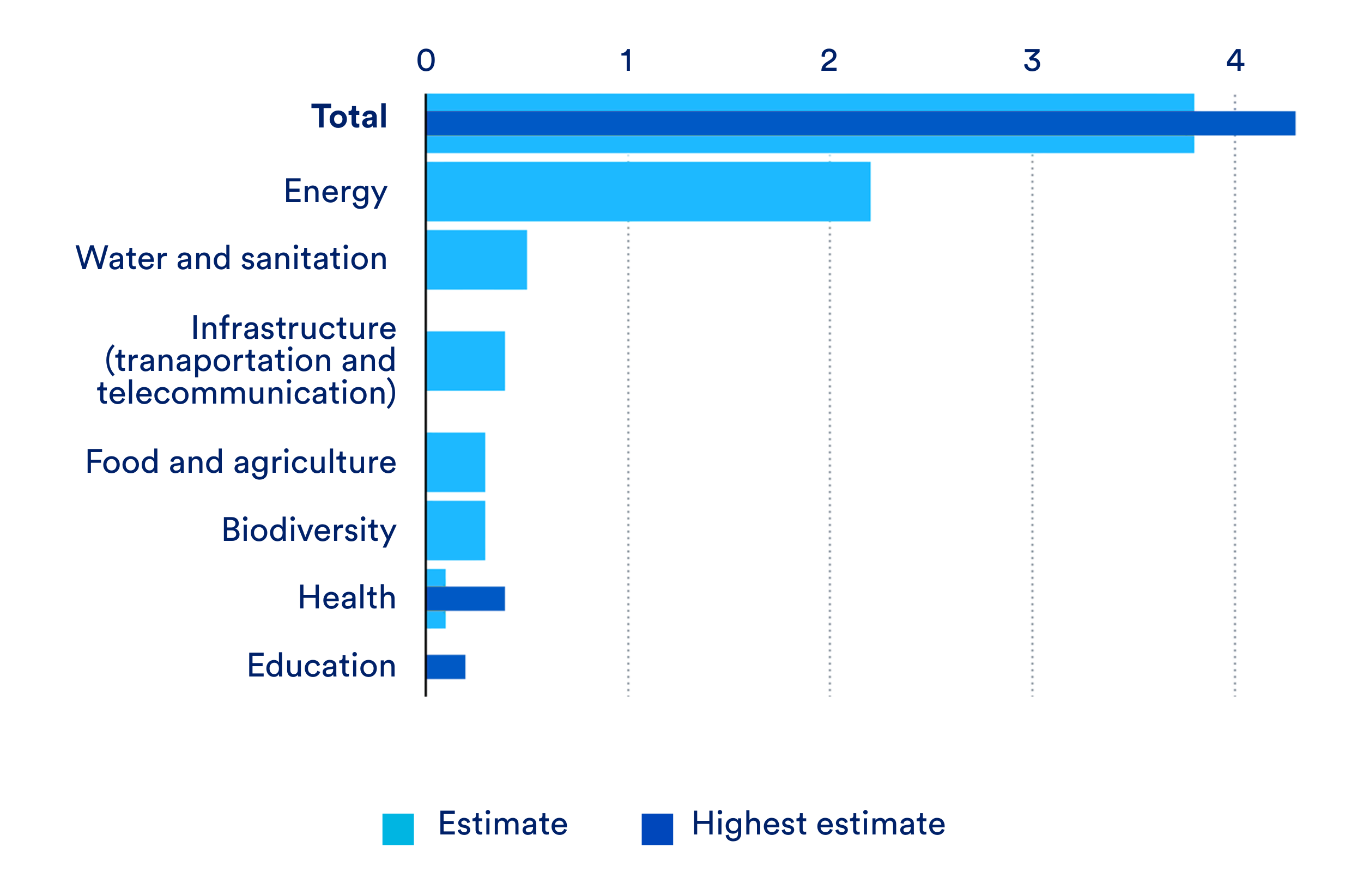

Much of the discussion on aid cuts has focused on humanitarian or health impacts. But the largest and most consequential funding gap is in the energy sector. The 2024 World Investment Report shows that least developed countries face significant investment gaps across key sectors like health, education, infrastructure, biodiversity, and agriculture — but the investment gap is greatest in the energy sector.

Figure 1. Estimated annual investment gap to reach the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by 2030, total and per sector, capital expenditure, trillions of dollars

Source: UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) SDG Investment Trends Monitor September 2023

Note: Investment refers to capital expenditure. The range for the health and education sectors reflects uncertainty about the size of the capital expenditure component in the total investment gap for the two sectors, for which the operational expenditure component is expected to be substantial.

Historically, Africa’s energy sector has relied heavily on external public funds from bilateral and multilateral partners, primarily disbursed as loans and guarantee instruments. Key financiers have included China, the World Bank, France, the United States, Italy, and the UK. But that landscape is shifting fast, with a majority dialing down foreign spending. Since 2015, Chinese development finance institutions (DFIs) have slashed African energy investments by 85%.

The stakes are high. Energy is the backbone of economic transformation. Without reliable, affordable power, Africa cannot build resilient industries, power digital economies, or meet basic development goals. If the continent is to future-proof its economies against aid volatility, African governments must take charge of their energy agendas.

There are five critical levers that will be foundational to this self-determined energy future.

1. Expanding and rebalancing Africa’s energy finance ecosystem

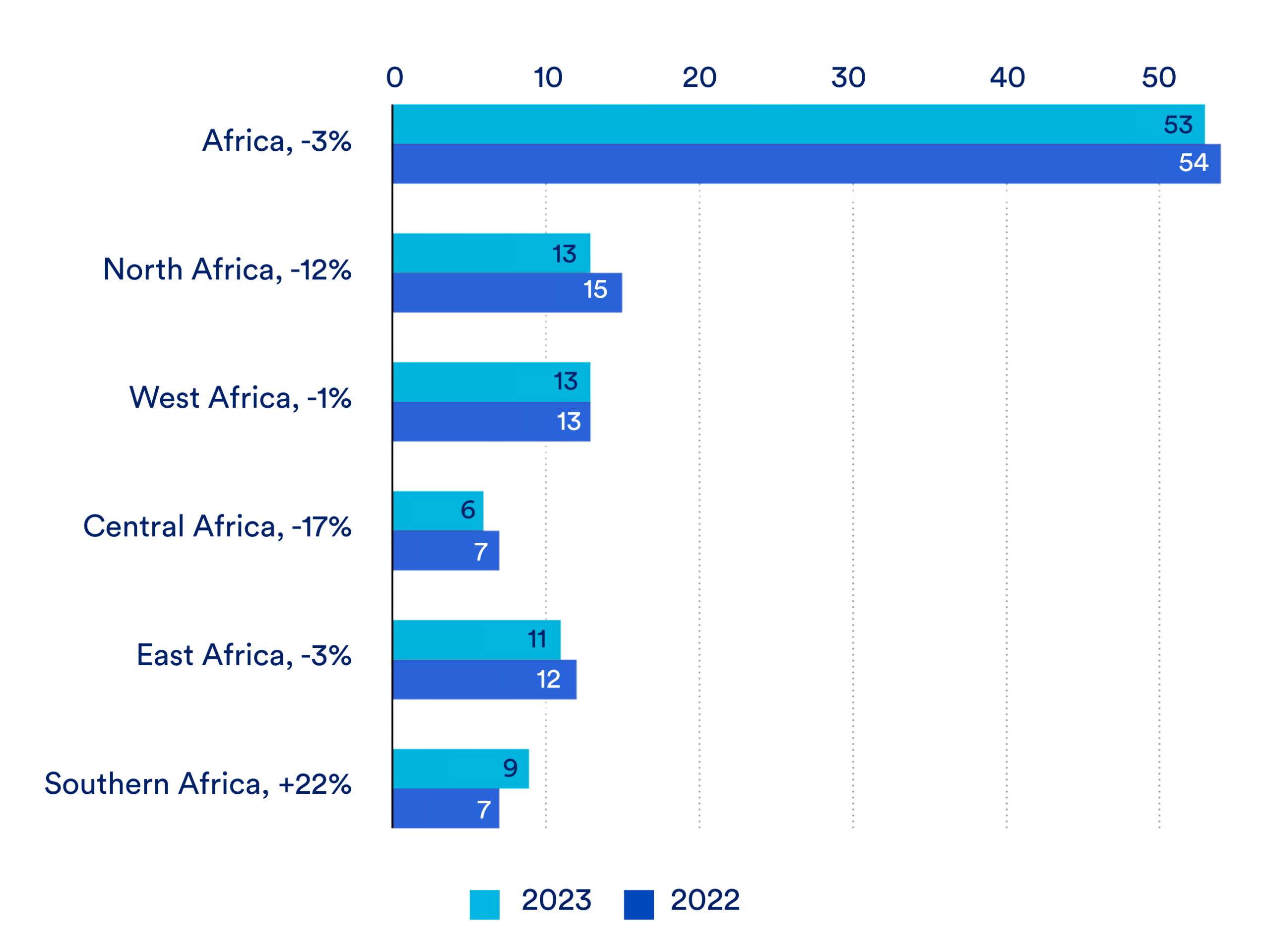

The decline in external public funding underscores the need for Africa to rope in more private capital. But that hasn’t been easy to achieve in the past. Between 2022 and 2023, most regions in Africa saw a drop in foreign direct investment, with a continent-wide decline of 3%. International project finance deals fell by 25% and halved in value.

Figure 2. Foreign direct investment (FDI) by region, billions of dollars, per cent, 2022-2023

Source: UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), FDI/MNE database.

Tighter financing requirements in a world of great economic and geopolitical uncertainty, the high cost of capital, among other constraints have limited the ability of African governments to attract private capital. This is the case even though some African countries have embraced investment policy measures that would facilitate, rather than hinder, investment in their countries (in contrast to some of the more restrictive investment policy postures adopted by some developed economies). Despite this, investment continues to favor developed and large emerging markets, and not poorer countries in Africa.

Still, African countries will need to do more internally to attract private capital. Promoting better governance and strengthening institutions should be at the top of that list. Promoting the rule of law, transparency, accountability, and regulatory certainty can also reduce the cost of doing business by creating a stable and predictable business environment for investors. This is a problem that requires strong political will and a genuine determination to change the status quo — not more aid.

In addition to capturing more private capital, African governments will also have to build domestic capital to fund the development of the region’s energy infrastructure; domestic funding will be the most critical game changer for building an energy-independent Africa. The reality is that no region in the world has achieved ground-breaking advancement by relying on the benevolence of others—and Africa is no exception.

Domestic funding will become available only as domestic savings grow. At 18% Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest domestic savings rate, compared to the global average of 36%. To grow domestic savings, governments must focus on strengthening local financial systems and building stable investment climates that incentivize savings. Implementing effective tax reforms and stemming illicit finance flows and capital flight will significantly boost domestic funds.

With more domestic funds in hand, African countries can invest in critical sectors like energy with the flexibility to opt for solutions that are responsive to the region’s development needs. High domestic savings will also limit the need to borrow from international capital markets (with the attendant currency devaluation risks), and limit country exposure to sudden shifts in these markets.

2. Tackling Africa’s electricity sector crisis

The finance gap isn’t the only obstacle to Africa’s energy progress. Deep structural inefficiencies in the power sector, especially among state-run utilities, are quietly eroding progress. On average, African utilities lose about 24% of the electricity they generate due to outdated infrastructure, power theft and underbilling. Transmission and distribution losses alone cost the continent an estimated 5 billion USD every year. West Africa — home to over a third of the 600 million Africans without electricity access– has some of the worst performing utilities, with some posting transmission and distribution losses exceeding 35%. In addition, many utility regulators set tariffs that are insufficient to cover the cost of service, making it difficult if not impossible for utilities to be financially viable.

Despite these challenges, central power grids will remain crucial to meeting Africa’s electricity needs and facilitating the continent’s overall structural economic transformation. Africa cannot build a competitive digital economy, power its growing cities, or host the industries and data centers of the future without reliable, affordable, always-available electricity. That will require governments to overhaul failing utilities—making them financially solvent, operationally efficient, and capable of delivering reliable service. Without these foundational fixes, the continent’s broader goals for economic transformation will remain out of reach.

3. Treating energy investment as a development multiplier

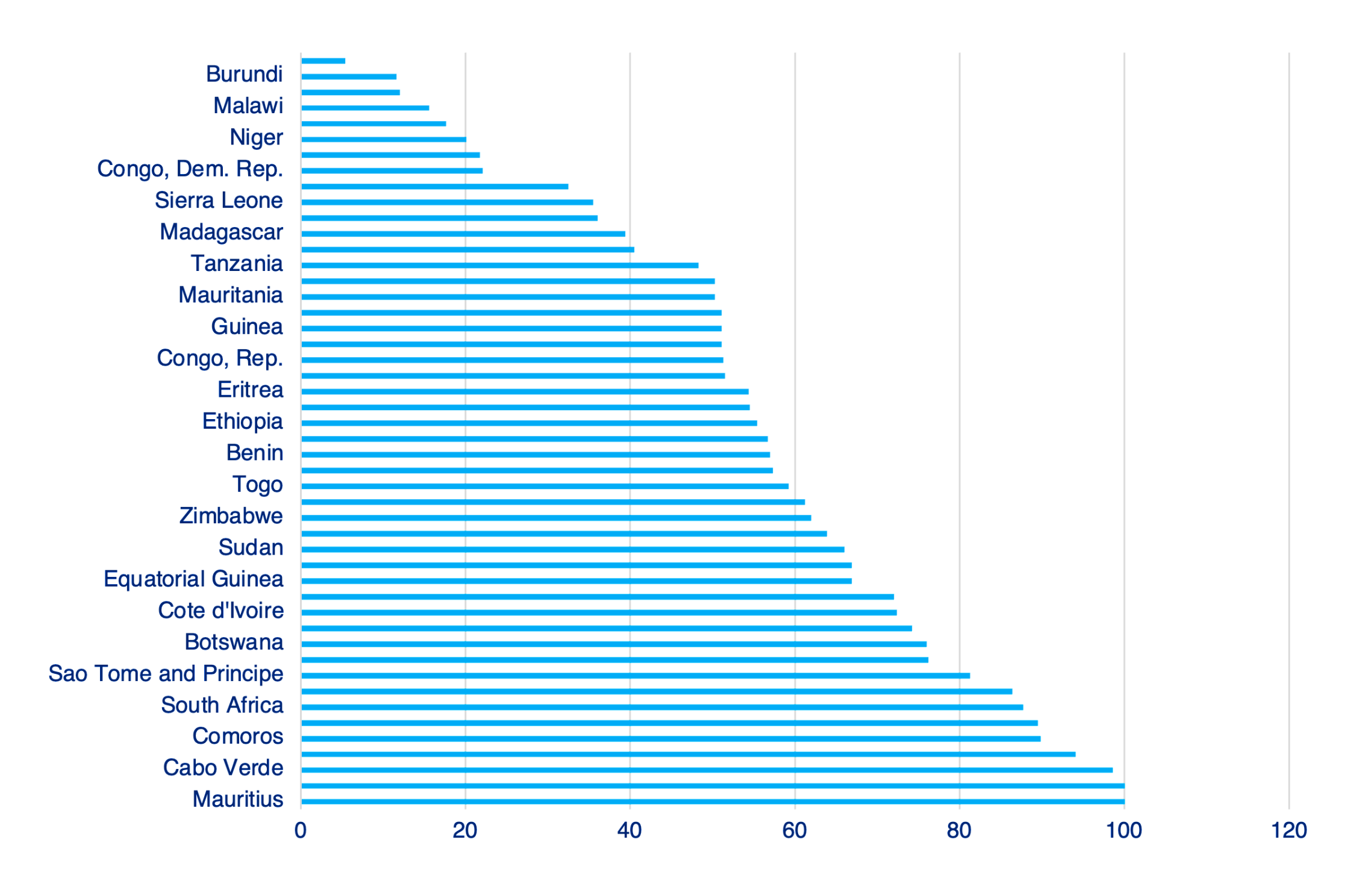

Energy is not a standalone sector—it powers the infrastructure that underpins every other facet of development. Hospitals, schools, industries, telecom networks, and agricultural value chains all depend on reliable electricity. The development of these sectors also builds sustained demand for energy; a key ingredient for viable energy markets. Unsurprisingly, African countries which score the lowest on the continent’s infrastructural development index also have the largest electricity access deficits.

Figure 3. Access to electricity (% of population) in 2023

Source: Africa Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI), 2024.

Source data: World Bank, 2023. World Development Indicators. Access to electricity (% of population)—Sub-Saharan Africa.

But progress is faltering. Today, many African countries are falling behind on key development targets in health, education, infrastructure, food and agriculture. The 2024 Financing Sustainable Development Report finds that many of the poorest countries in the world are backtracking on development gains primarily due to debt burdens and the rising costs of borrowing.

Least developed countries (LDCs) — most of which are in Africa– are expected to spend $40 billion annually from 2023-2025 on servicing debt alone; a 50% increase from 2022 debt servicing levels of $26 billion per year. At current levels, LDCs are spending 12% of their domestic revenue on debt servicing; more money than they are investing in critical sectors like health and education.

This underinvestment poses a serious threat to Africa’s long-term growth trajectory. Yet it also highlights a critical opportunity: investing in energy not just as an end in itself, but as a multiplier of development impact. According to the Business and Sustainable Development Commission, achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in just four sectors- energy and materials, cities, food, agriculture, and health—could unlock market opportunities of nearly $12 trillion — almost four times the size of Africa’s current GDP.

Africa doesn’t need more aid. Rather, it needs a more equitable global financial system– one that does not burden countries with expensive loans and rigid repayment terms that drain resources that could be invested in critical development interventions.

4. Strengthening regional integration to drive industrial growth and energy resilience

Africa’s path to energy independence cannot be pursued in isolation. Building sustained energy demand—and the investment that follows—will require deeper interregional collaboration and a strong agenda to boost African industry and manufacturing. Today, Africa accounts for roughly 3% of global trade, primarily driven by the export of raw commodities such as ores, metals and fuels. These extractive sectors generate little employment and contribute minimally to structural economic transformation. Much of the value is captured abroad, and few benefits remain on the continent

In contrast, intra-African trade is more promising and has been resilient to recent global economic shocks. It comprises up to 45% of manufactured goods; the type of trade that creates jobs, builds domestic industries, and drives long term electricity demand. By 2050, a quarter of the world’s population will be African; this represents a significant, untapped market opportunity for consumer goods, energy, transport, and more. If successfully executed, the African Continental Free Trade Agreement can catalyze the development of regional value chains, stimulate investment in infrastructure, and unlock new energy demand from manufacturing and industry.

Regional integration can also help to circumvent one of the biggest barriers to energy development: small and fragmented energy markets. In Africa, some of the countries with the highest cost of electricity are those with small markets that rely heavily on generation sources with high operational costs, such as thermal generation. Integrating power systems and markets across borders will allow such countries to diversify away from expensive generation sources within their borders to cheaper generation from other countries.

To date, regional power pools across Africa have operated with varying rates of success. But with stronger coordination, African governments can strengthen and invest in the infrastructure necessary for power trade while building strong regional institutions, regulatory frameworks, and policies. A more connected continent will be better positioned to meet its energy needs, compete globally, and chart a path toward economic self-reliance.

5. Elevating an African agenda over external determinism

Ultimately, the African continent must pursue an energy agenda that emphasizes long term energy security, development, and environmental sustainability with the view that Africa, rather than development partners, will be the biggest investors in this enterprise. For far too long, Africa’s energy agenda has been modelled after the dictates of external funders. From decisions about energy supply sources to the structure of power utilities and markets, Africans have been followers rather than determinants of their own energy agenda.

It is unfair to future Africans if the current generation abdicates the responsibility for making important decisions about the continent’s energy future, leaving those decisions to be made in Brussels, Washington, or Beijing. Those decisions can and must be made and led from Africa. But this will only be possible if Africans take full responsibility for stewarding that future: this means planning for it, funding it, and building it.

Africa can by no means act as an island in pursuing this self-determined future. Global partnerships will remain central to any new energy agenda— however, African leaders must come to the global stage prepared to negotiate differently. Africa’s new energy partnerships must transcend aid and be developed to build lasting markets and foster local innovation. Only then can the “death of aid” be turned into an opportunity for Africa to build an energy future on its own terms.