Technology Options and Optimal Pathways to a Net-Zero Electricity System in Nigeria Across Different Timelines

Nigeria faces a dual and urgent challenge: rapidly expanding electricity supply to support economic growth and industrialization, while transitioning its power sector toward net-zero carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions. Electricity demand is rising due to population growth, urbanization, and development ambitions articulated in national policy frameworks, including the Energy Transition Plan and Nigeria Agenda 2050. At the same time, Nigeria’s electricity system remains characterized by inadequate capacity, poor reliability, and heavy reliance on fossil fuels, as well as off-grid diesel and gasoline generators.

This study, Technology Options and Optimal Pathways to a Net-Zero Electricity System in Nigeria Across Different Timelines, provides a comprehensive, scenario-based comparison of how Nigeria’s electricity system could achieve net-zero CO₂ emissions by 2050, 2060, or 2070, considering the implications of restricting the deployment of firm low carbon technologies. The results offer a clear decision framework for policymakers: the timeline and technology choices Nigeria makes are fundamentally development decisions, with major implications for affordability, reliability, and energy security.

Methodology

We employed a national, stylized TIMES capacity expansion model to assess least-cost pathways for Nigeria’s electricity system under alternative net-zero emissions timelines (2050, 2060, and 2070). The model optimizes generation, storage, and firm capacity investments subject to electricity demand growth, technology cost trajectories, operational constraints, and emissions limits. Our scenarios evaluate the availability of key low-carbon technologies, including nuclear power, natural gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS), and concentrated solar power (CSP). A high-electricity-demand sensitivity aligned with Nigeria Agenda 2050 is also assessed to reflect a high-income development pathway. Results include installed capacity, electricity generation mix, system costs, and investment requirements over the period 2020–2070.

Key Findings

- Rapid capacity expansion without deep decarbonization in the business-as-usual scenario: Under a business-as-usual (BAU) case, Nigeria’s electricity system expands rapidly to meet rising demand, but remains dominated by unabated fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, resulting in a large, emissions-intensive power system by mid-century. While off-grid diesel and gasoline generation is phased out and replaced largely by off-grid solar PV, and renewables grow steadily, the absence of climate constraints leads to continued reliance on emitting gas generation. As a result, BAU delivers scale but not deep decarbonization.

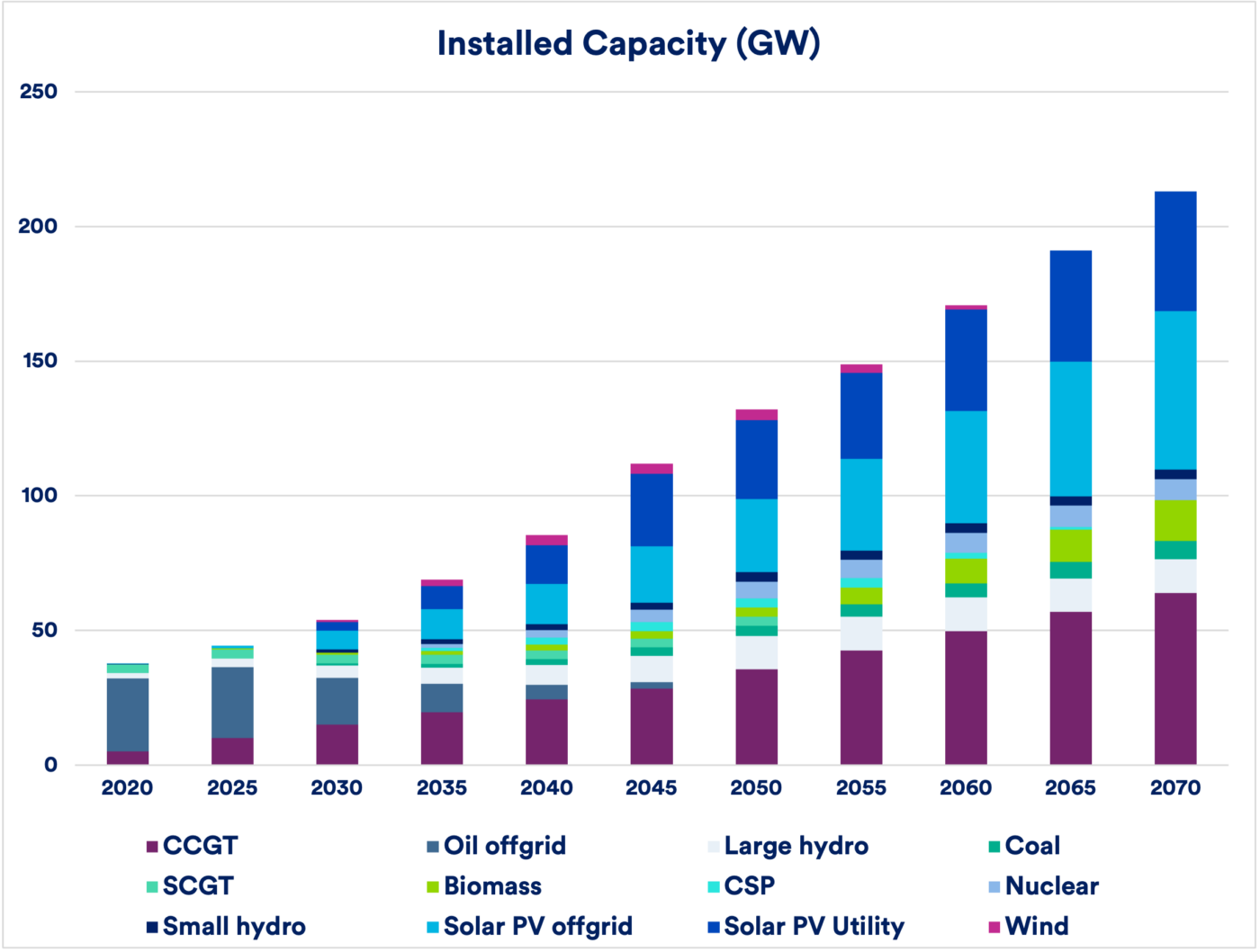

BAU Scenario: Installed Capacity and Electricity Generation Mix

Figure 1. Installed electricity capacity (top) and electricity generation mix (bottom) under the business-as-usual scenario. Total installed capacity increases more than fivefold, driven primarily by unabated natural gas generation. Despite modest growth in renewables and a small nuclear build-out, fossil fuels remain the dominant source of electricity throughout the period.

- Solar power is the backbone of Nigeria’s net-zero electricity system, but cannot deliver reliability alone: Across all net-zero timelines, utility-scale and off-grid solar PV provide 37–55% of total electricity generation by 2050, reflecting Nigeria’s strong solar resource and declining technology costs. Off-grid solar plays a critical role in displacing costly diesel and gasoline generators, while utility-scale PV becomes a major contributor to grid supply. However, high solar penetration increases reliance on balancing resources and grid flexibility.

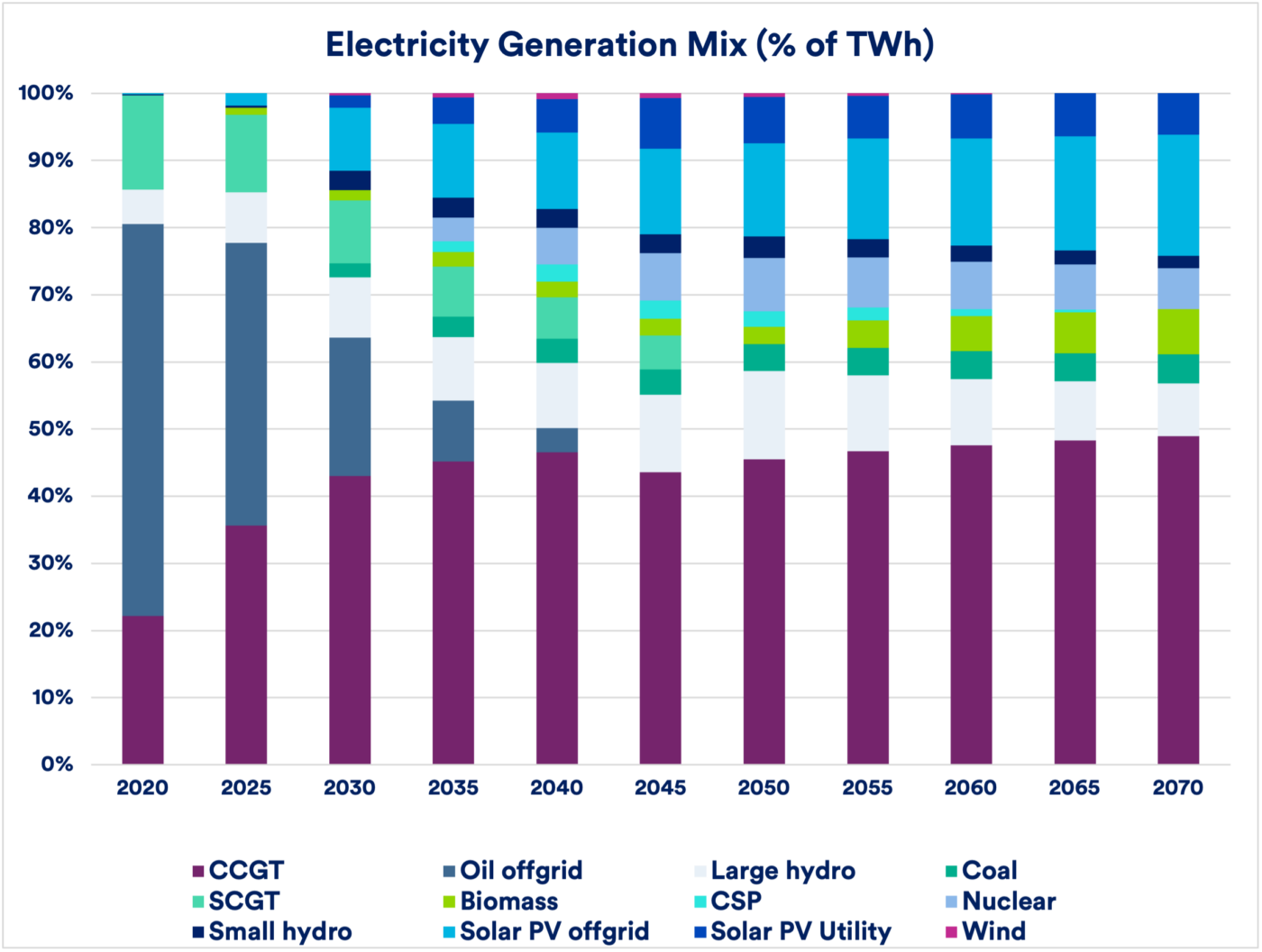

NZ60_All Scenario: Installed Capacity and Electricity Generation Mix

Figure 2: Installed electricity capacity (top) and electricity generation mix (bottom) under the net-zero by 2060 scenario with all technologies available. The figure shows the rapid expansion of solar PV alongside a declining reliance on unabated fossil fuel generation, supported by the deployment of firm low-carbon technologies to maintain system reliability.

- Battery storage becomes increasingly important as solar expands, but is most effective when complementing firm capacity: Battery energy storage systems (BESS) grow rapidly in all net-zero scenarios to manage hourly variability and meet evening peak demand. Their role is particularly pronounced in scenarios with high solar penetration and restricted firm capacity. However, using batteries to substitute for firm, dispatchable generation at system scale requires very large capacity additions and significantly increases system cost.

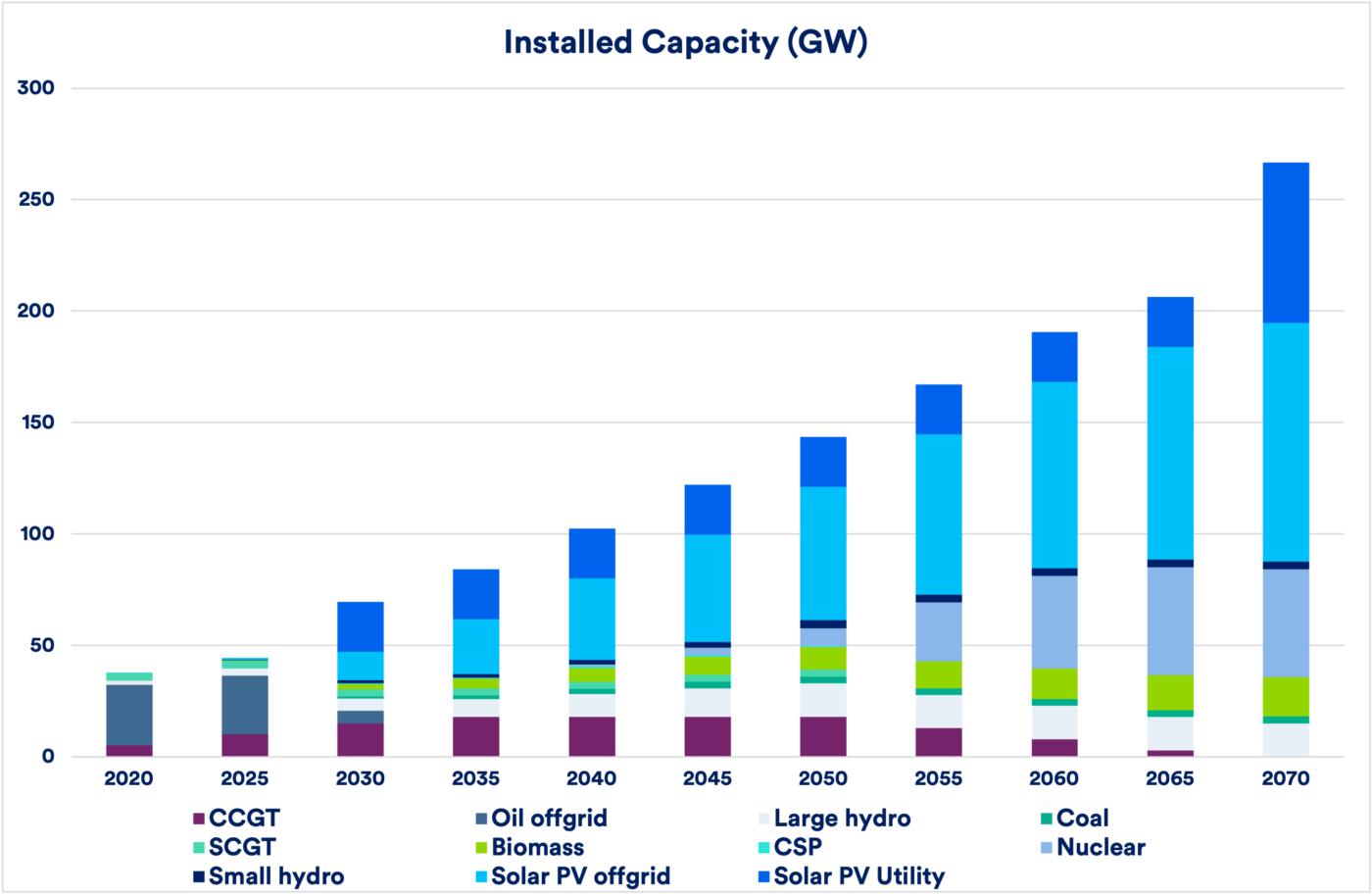

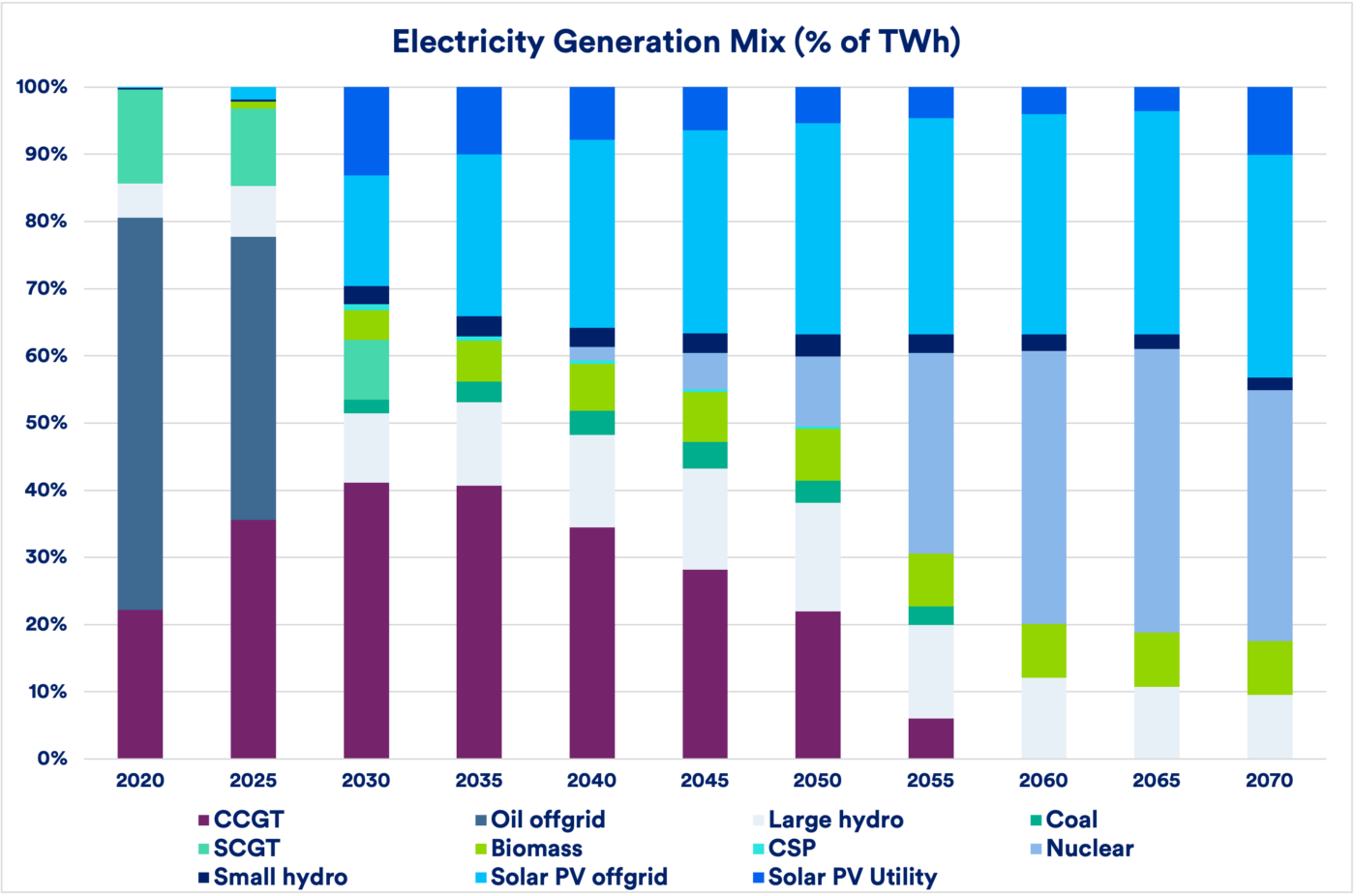

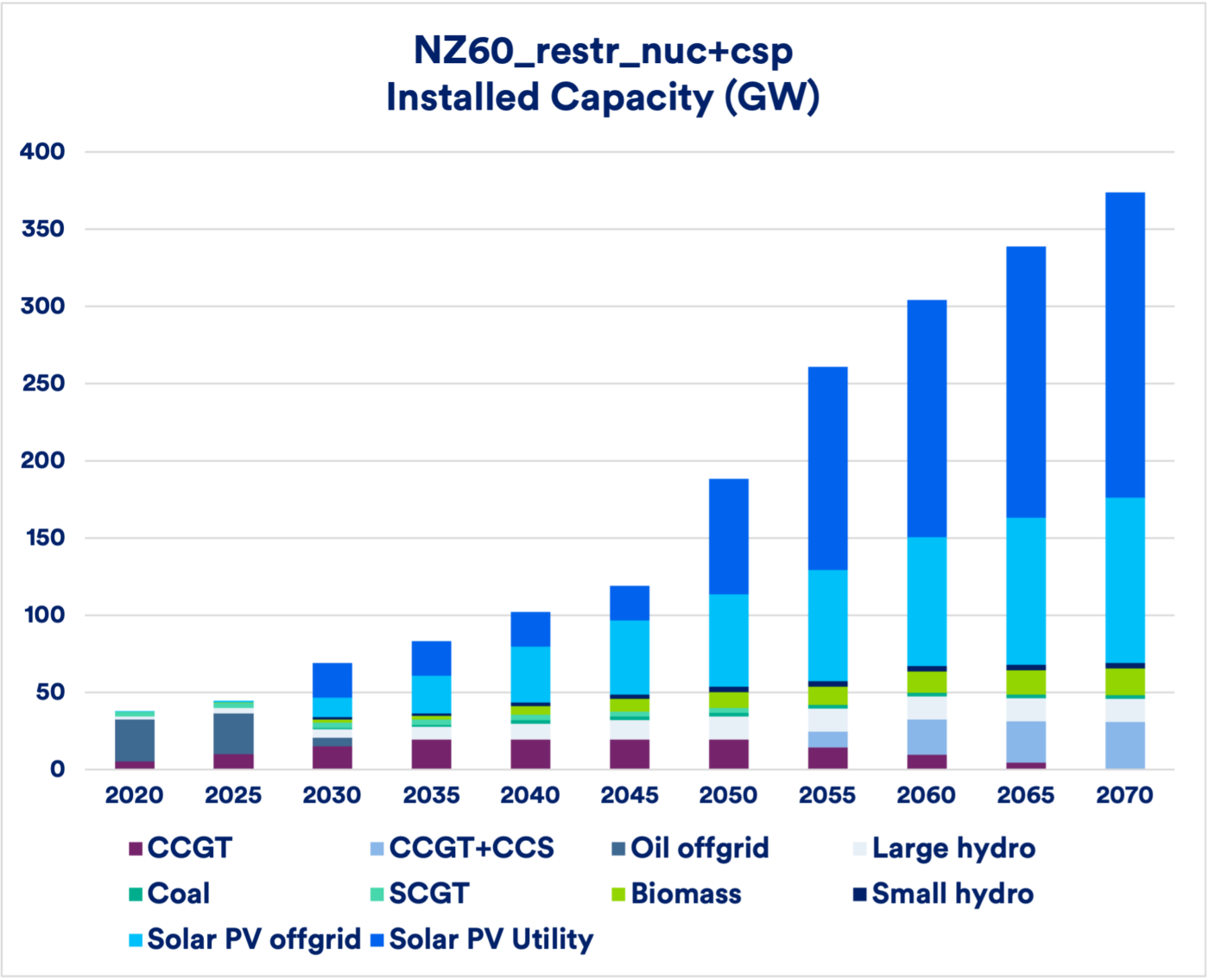

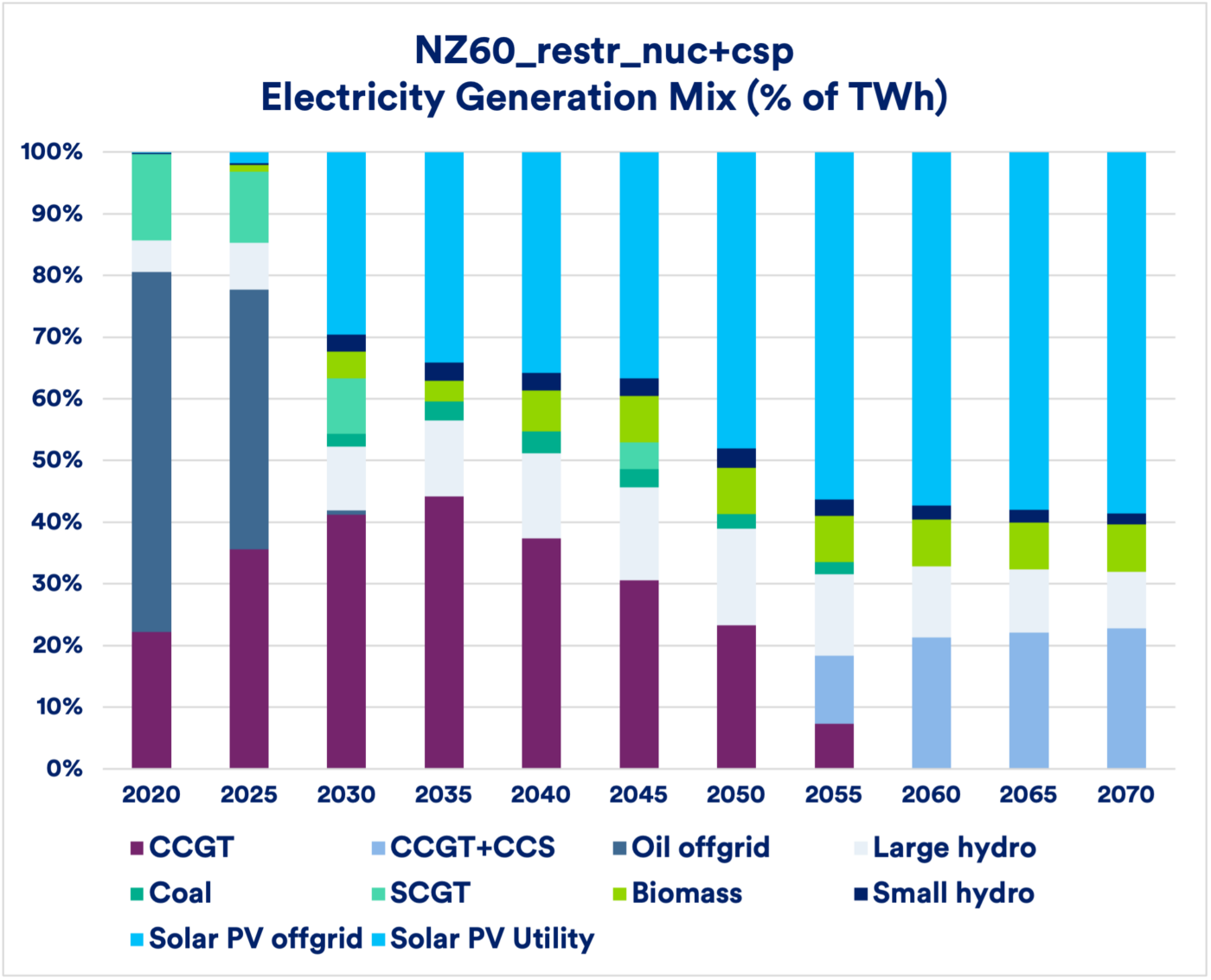

- Technology openness delivers the lowest-cost and most reliable net-zero pathways: The analysis finds that the lowest-cost net-zero electricity system is achieved when all low-carbon technologies are allowed to compete, including nuclear power and natural gas with CCS. When nuclear is available, it supplies 33–41% of electricity generation by mid-century, significantly reducing the need to overbuild variable renewables and storage. Restricting nuclear or gas-CCS forces Nigeria to compensate by deploying much larger volumes of solar PV and batteries, increasing total installed capacity by approximately 50% and raising annual investment requirements by about 7%. In practical terms, Nigeria must build substantially more infrastructure to deliver the same amount of reliable electricity.

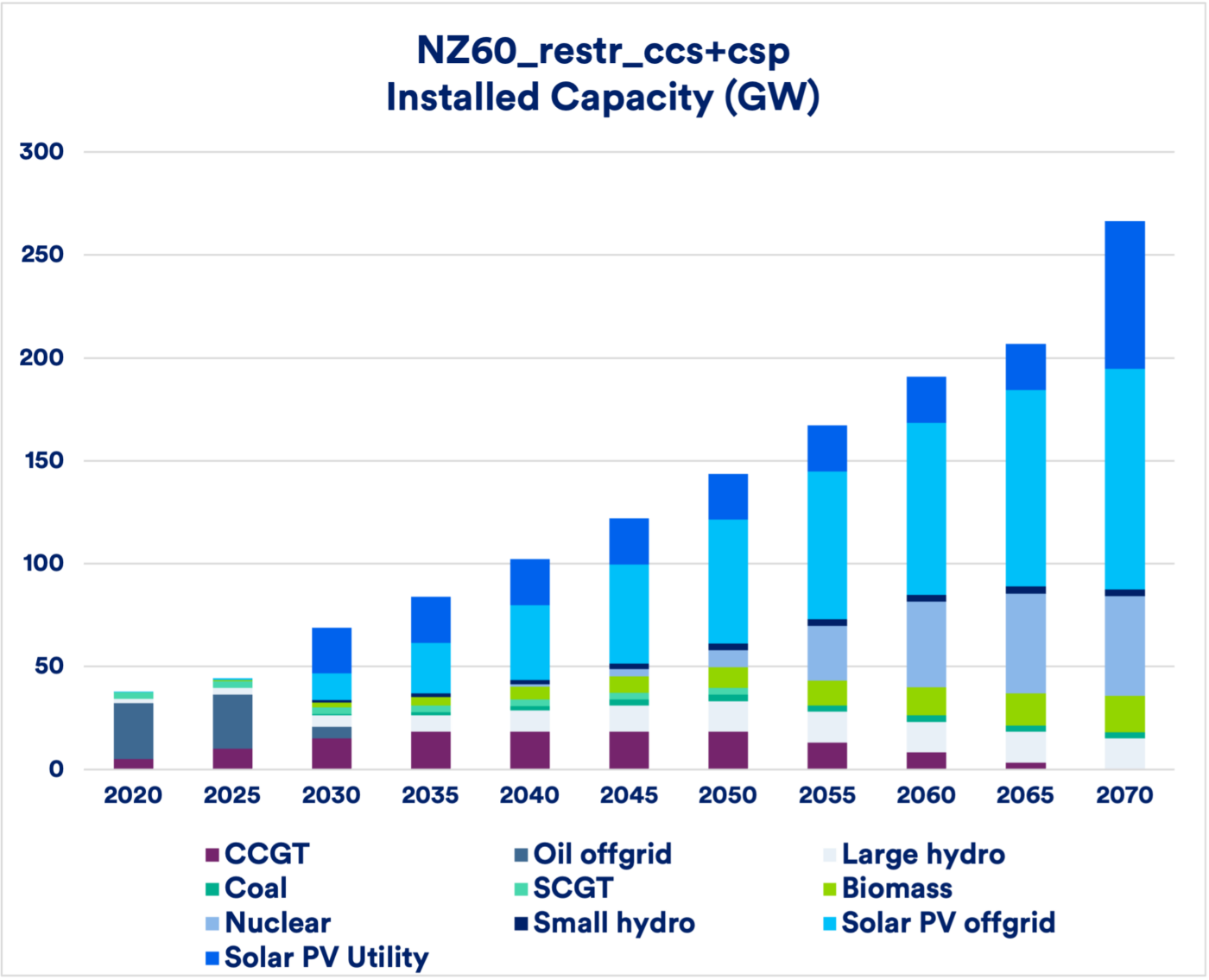

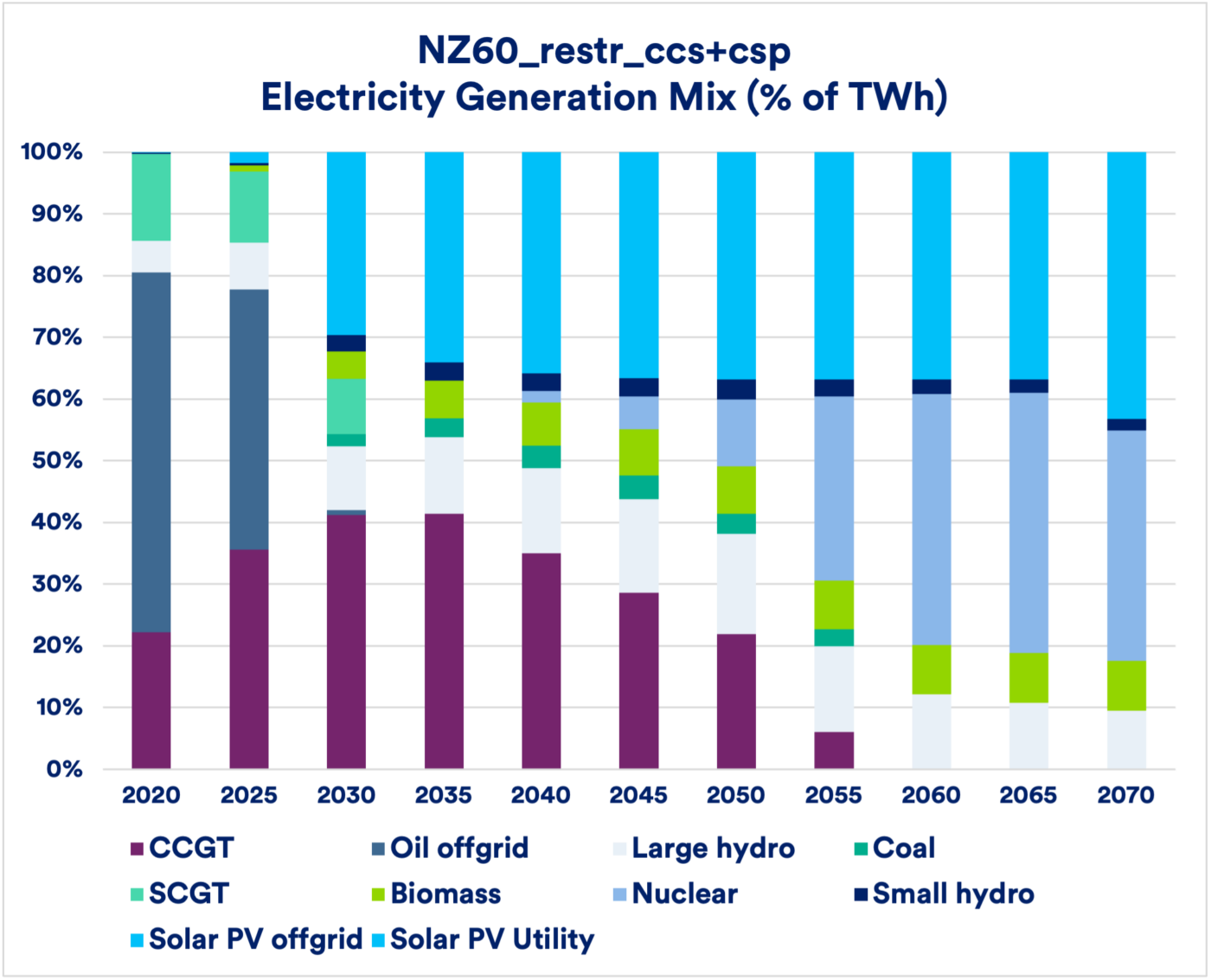

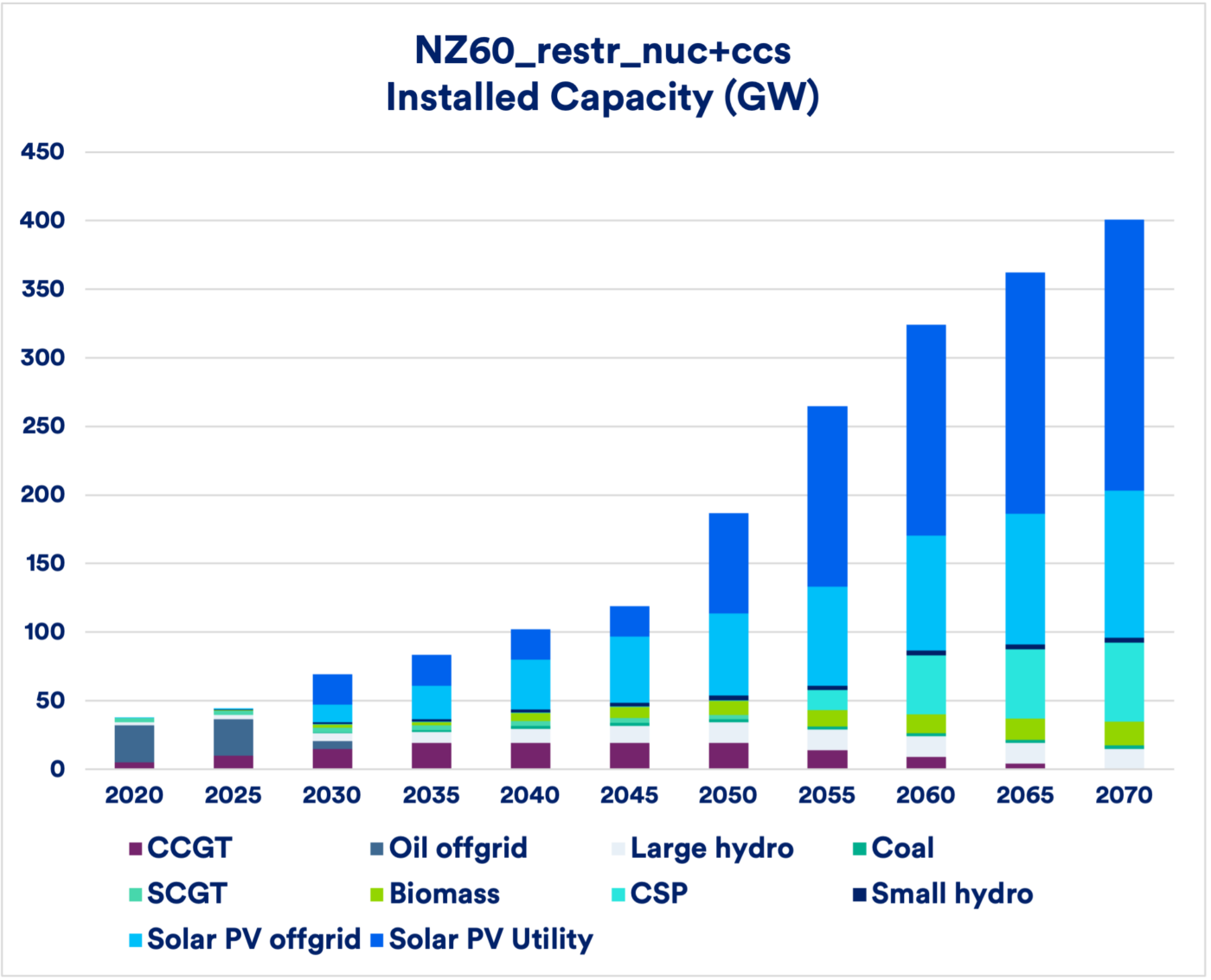

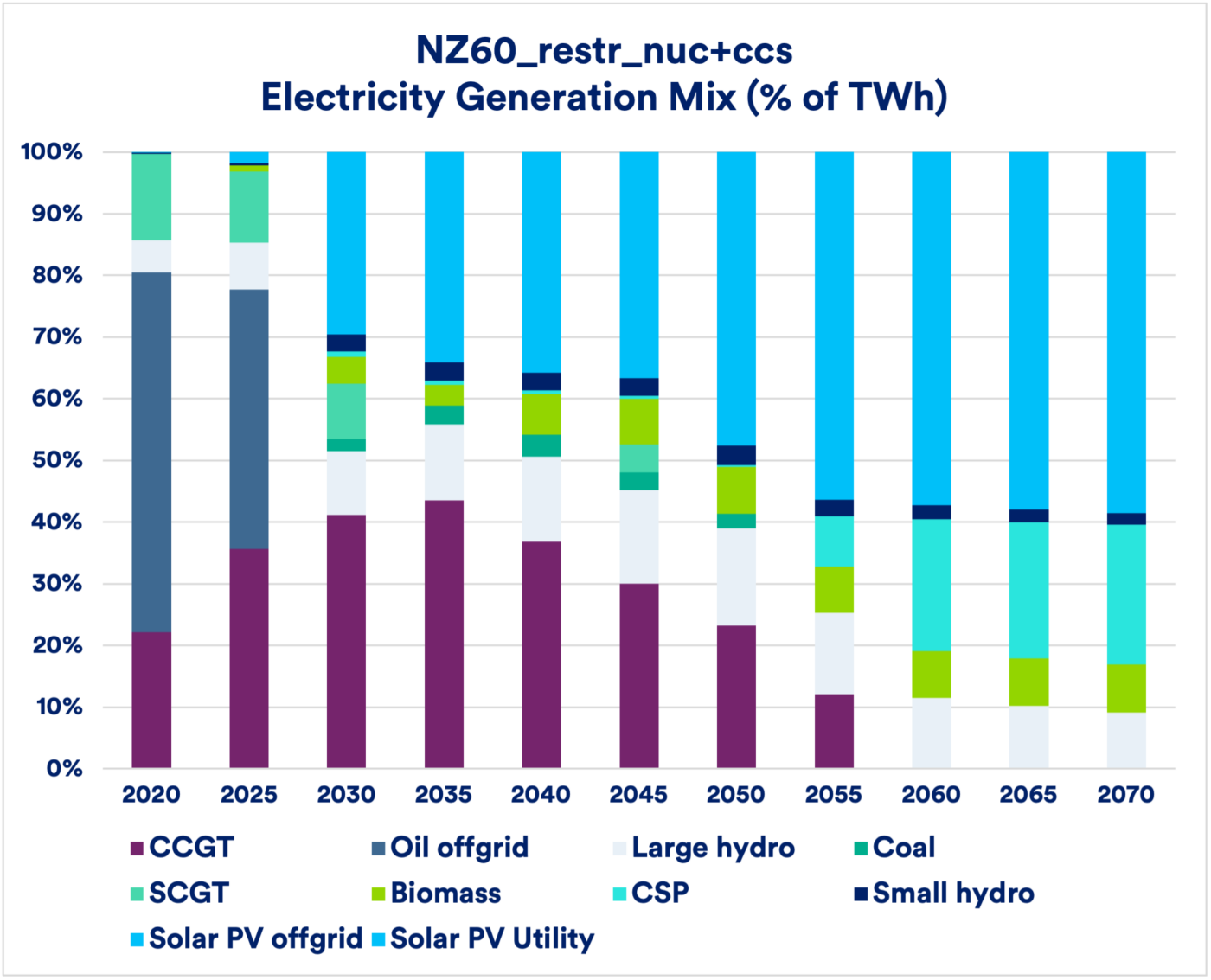

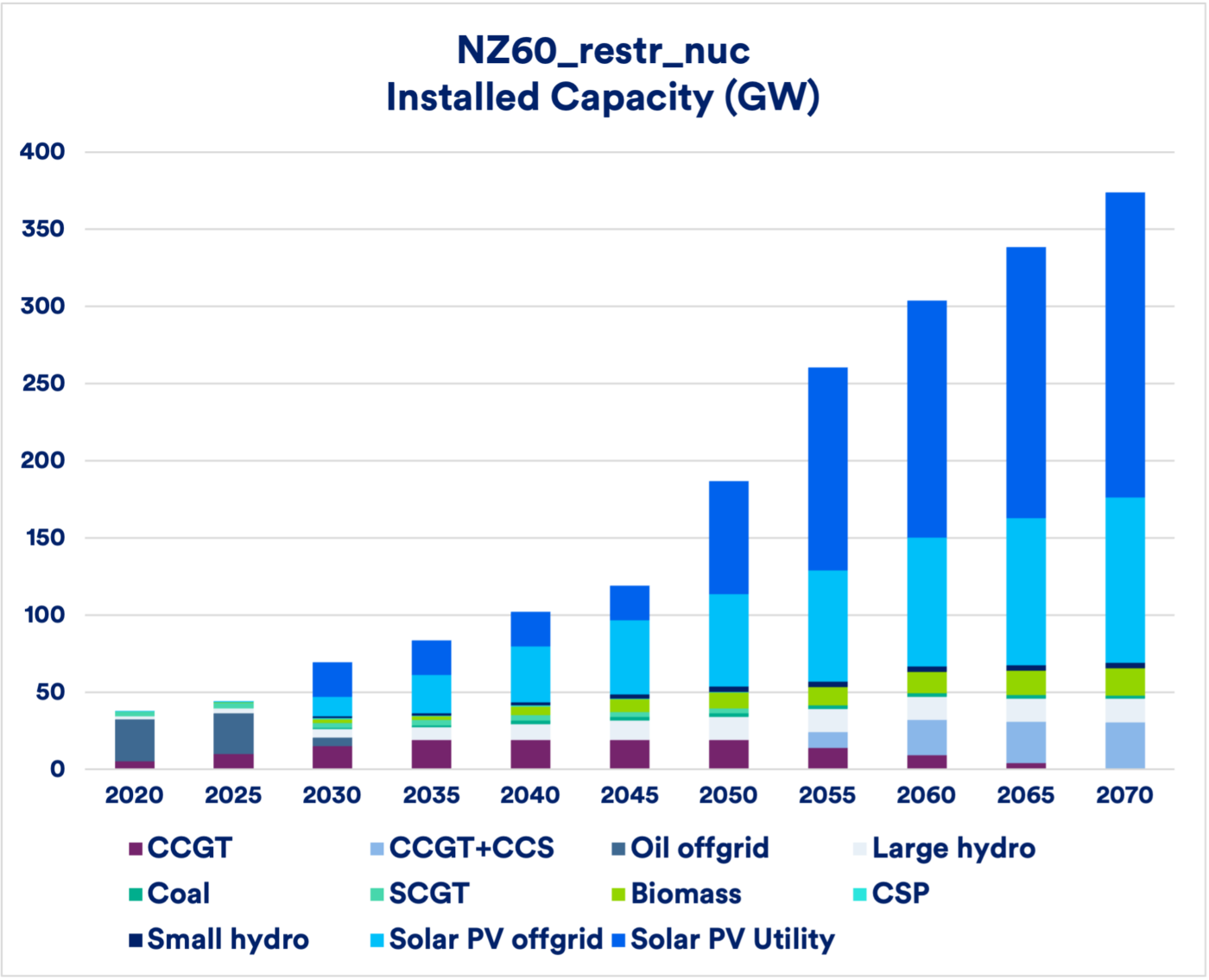

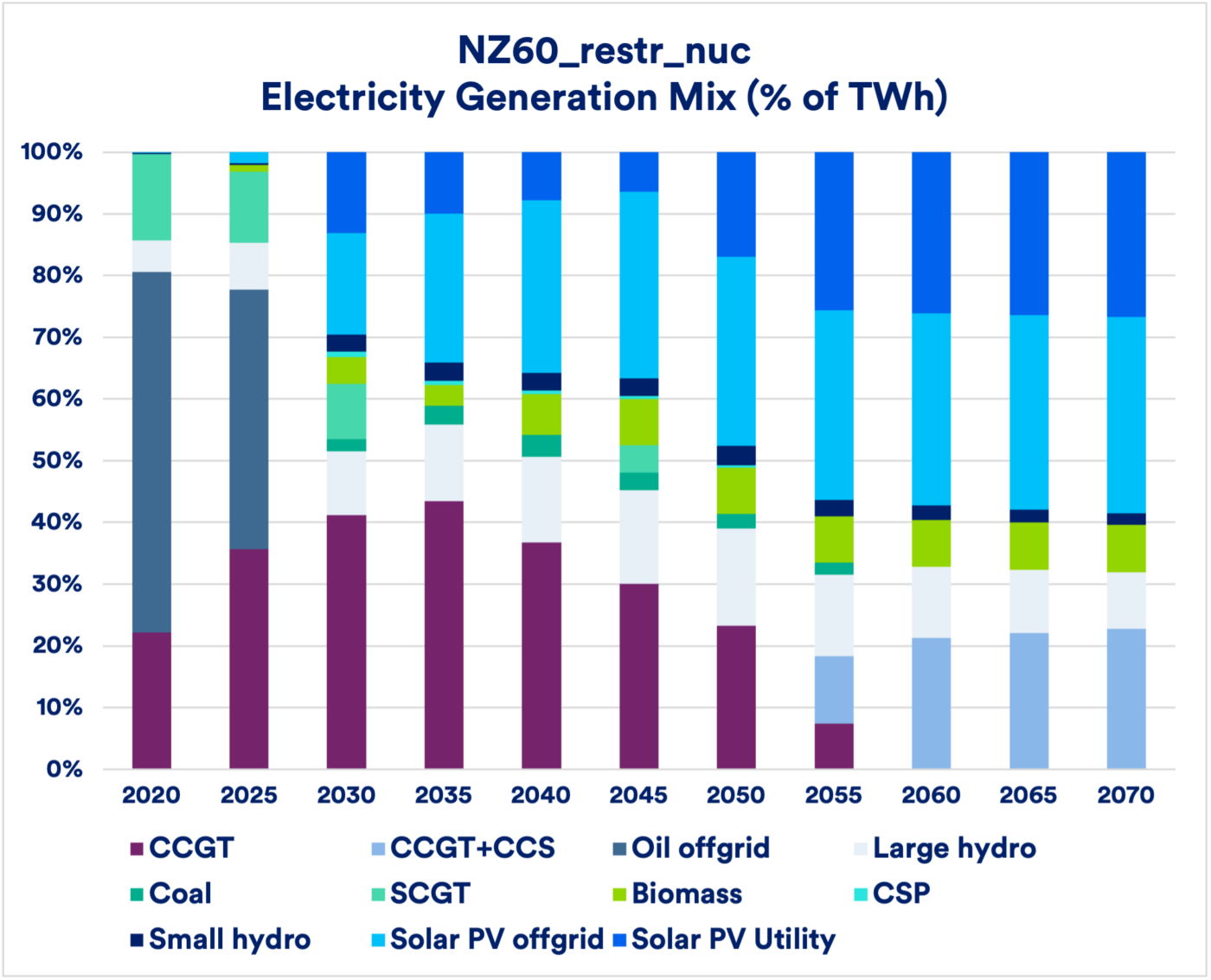

NZ60 Variants: Installed Capacity and Electricity Generation Mix

Figure 3. Capacity and generation mix in Nigeria’s net-zero-2060 scenarios with technology restrictions. This figure shows four variants that prohibits certain firm low-carbon technologies: NZ60_restr_nuc (no nuclear), NZ60_restr_nuc+ccs (no nuclear or CCS), NZ60_restr_nuc+csp (no nuclear or CSP), and NZ60_restr_ccs+csp (no CCS or CSP). Comparison of net-zero pathways with restricted firm low-carbon technologies highlights substantial overbuilding of solar PV and battery storage, leading to higher total installed capacity and increased system costs.

- Net-zero timelines have similar long-term costs: Under baseline demand assumptions, all net-zero timelines (2050, 2060, and 2070) require US$7–10 billion in average annual investment, with earlier timelines not dramatically more expensive than delayed ones.

- Nigeria Agenda 2050 fundamentally changes the scale of the electricity transition: In the high-demand scenario aligned with Nigeria Agenda 2050, electricity demand increases nearly sixfold by 2050. Meeting this demand while achieving net-zero emissions nearly triples total system costs, increases average annual investment from US$9.3 billion to US$35.8 billion, and drives a 300% expansion in installed capacity through rapid deployment of nuclear power, solar PV, and battery storage. Development ambition, not climate ambition alone, becomes the dominant driver of system scale and cost.

System Pathways Across Timelines

In the business-as-usual scenario, Nigeria’s installed electricity capacity grows more than fivefold by 2070, reaching over 200 gigawatts, with continued dominance of fossil fuels, particularly natural gas. While renewables expand, emissions remain high and system reliability challenges persist.

In net-zero-by-2050 scenarios with all technologies available, Nigeria transitions rapidly away from unabated fossil generation. Nuclear power ramps up in the 2040s, hydropower and biomass are fully exploited, and solar PV expands substantially, especially in off-grid applications. Total installed capacity reaches roughly 160 gigawatts by 2050, rising further thereafter to meet growing demand.

Net-zero-by-2060 and net-zero-by-2070 pathways follow similar patterns but allow for more gradual transitions. Delayed timelines reduce near-term investment pressure but require steeper capacity build-outs later, particularly if firm low-carbon technologies are constrained. Across all timelines, the absence of nuclear power consistently leads to larger, more complex, and more expensive systems.

Policy Implications

- Net-zero electricity is a development and reliability strategy, not just a climate target: Well-designed net-zero pathways improve energy security, reduce exposure to fossil fuel price volatility, and support long-term economic growth. Nigeria’s electricity transition should therefore be embedded within broader development planning.

- Technology-neutral policies are essential to minimize cost and risk: Prematurely excluding firm low-carbon technologies such as nuclear power significantly increases system size, infrastructure needs, and long-term costs. Policymakers should preserve optionality and allow technologies to compete on cost and performance.

- Solar and storage investments must be paired with firm capacity and grid upgrades: Solar PV and battery storage are indispensable, but cannot alone ensure reliability at scale. Investments in firm generation, transmission, distribution, and system operations are needed to support high renewable penetration.

- Electricity planning must be coordinated with industrial, land, and infrastructure policy: The scale of capacity expansion required under all net-zero pathways, particularly under Nigeria Agenda 2050, has implications beyond the power sector. Large-scale deployment of solar PV, nuclear power, transmission infrastructure, and battery storage will affect land use, siting, workforce needs, and supply chains. Coordinated planning across sectors is therefore essential to avoid implementation bottlenecks.

- Achieving Nigeria Agenda 2050 requires unprecedented electricity investment: High-growth futures demand early planning, major institutional strengthening, and large-scale mobilization of international climate and development finance. Electricity system expansion is a prerequisite for industrialization and economic transformation.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that Nigeria can achieve a net-zero emissions electricity system that is affordable, reliable, and aligned with national development goals. The lowest-cost and most resilient pathways are those that allow a broad suite of low-carbon technologies to compete, combining solar power with firm, dispatchable resources such as nuclear power and gas with CCS. The choice of timeline and technologies is ultimately a strategic development decision. With the right policy signals, institutional readiness, and financing, Nigeria’s electricity transition can support both climate objectives and long-term prosperity.