Central and Eastern Europe’s energy crossroads: What new public opinion data tells us about the path forward

Contributing authors: Luke Shore, Strategy Director, Project Tempo and Bartek Orzel, Polish Lead, Project Tempo

Across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the political landscape around climate and energy policy is entering a decisive phase, where political will underpinned by public acceptance will determine course of the energy transition. New polling released through Project Tempo’s EuroPulse Dashboard highlights a complex but increasingly urgent reality: voters across the region remain deeply concerned about energy costs and reliability, and national security. These concerns are shaping how climate policy is perceived, debated, and ultimately implemented.

For policymakers, the data reinforces a core message Clean Air Task Force outlined in Strategy at the Geopolitical Crossroads: The Imperative for Secure and Clean Energy in Central and Eastern Europe: CEE needs a diversified, technology-neutral, and reliability-focused decarbonisation strategy. A strategy that addresses affordability and security concerns while simultaneously accelerating emissions reductions.

Part 1. What the new data shows: Voters want security, affordability, and realistic pathways

Project Tempo’s nationally representative survey was conducted across nearly every EU market and the UK. With almost 50,000 respondents, it offers one of the most comprehensive snapshots to date of European public sentiment around climate, energy, and political priorities.

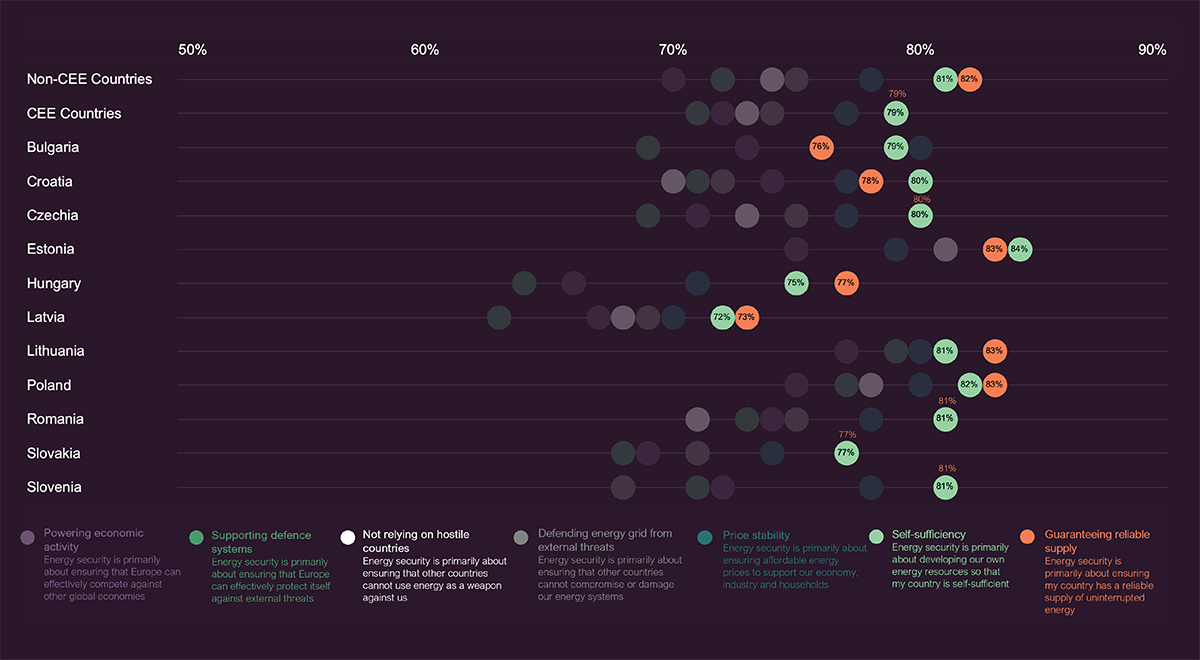

Across Central and Eastern Europe,1 the data reveals a pronounced voter pessimism, with 53% of voters believing their country is going in the wrong direction. Voters rank climate change 16th out of 18 issues tested, pushed down by more immediate policy priorities such as the economy, public service provision and security a persistent source of anxiety, however, with CEE voters placing importance on national self-sufficiency and uninterrupted, reliable energy supply, as shown in the graph below.

Figure 1. Main public concerns

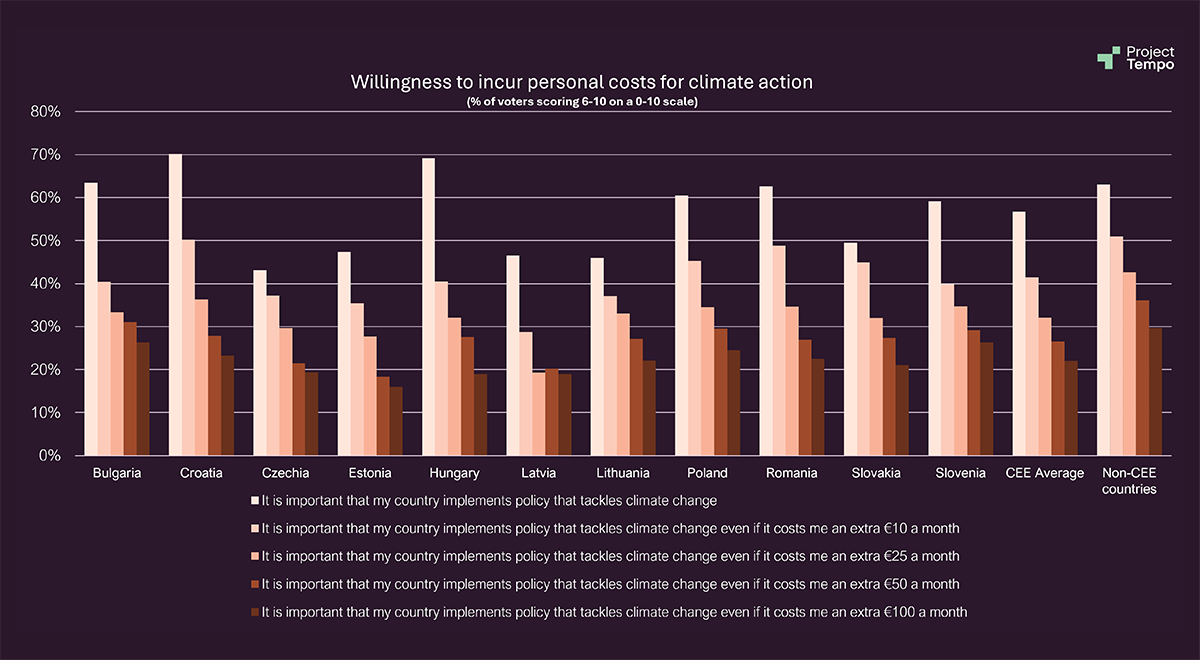

Regarding attitudes towards climate and the energy transition, 62% of voters in Central and Eastern Europe acknowledge that climate change is real and driven by human activity, and most broadly support the aims of the European Green Deal (70% say climate change is a major threat for Europe). Yet, despite this general agreement on the need to address climate change, there is a clear reluctance to accept personal costs associated with these measures. CEE voters are more cost-sensitive than non-CEE voters as shown in the graph below.

Figure 2. Willingness to incur personal costs for climate action

Most CEE voters believe there are economic opportunities to be unlocked by the Clean Industrial Deal, and that Europe’s industries will need to adapt to stay competitive. There is support for deploying a range of clean energy and climate technologies, including62% support for increasing wind power, and 65% support for expanding solar power, 62% support for actively removing carbon from the atmosphere through carbon dioxide removal technologies, and 44% support for building more nuclear power stations (compared to 30% opposed).

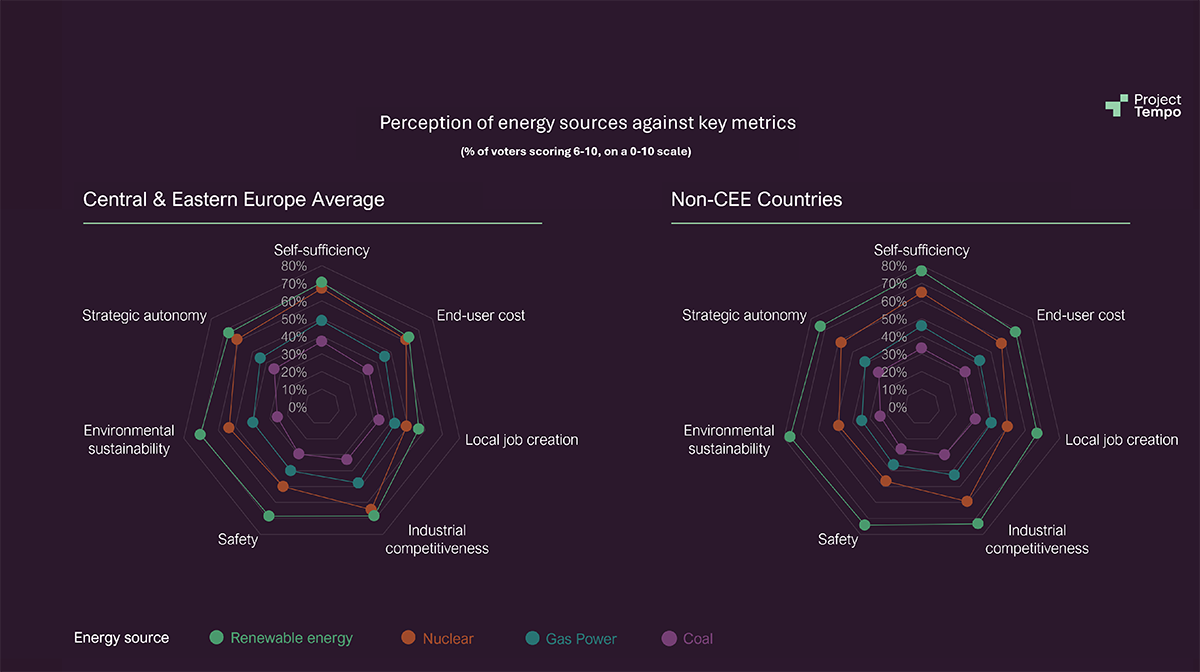

In the region, support for nuclear energy is higher than the European average, with CEE voters seeing nuclear energy and renewables as providing similar benefits: supporting self-sufficiency, lower end-user costs, and industrial competitiveness, as shown in the chart below:

Figure 3. Perceptions of energy sources against key metrics

Part 2. A CATF approach: Building a resilient clean energy system

Project Tempo’s findings echo CATF’s vision that climate and energy ambition in CEE must be paired with practical, affordable, resilient, and secure pathways to achieve it.

For CEE countries, clean firm power, such as nuclear energy (including SMRs), advanced geothermal energy, and gas with carbon capture, offers a pathway to deliver reliable, round-the-clock electricity while reducing exposure to volatile fossil fuel markets. These technologies can support industrial competitiveness (enabling steel, cement, chemical, and manufacturing sectors to decarbonise without sacrificing productivity), deliver 24/7 reliability (complementing renewables and reducing dependence on weather patterns) and enhance energy sovereignty (limiting the need for imported fuels or technologies).

Moreover, maintaining technology neutrality is essential for addressing public concerns about cost. By keeping multiple clean energy pathways open, CEE governments can avoid premature lock-in to a single technology or supply chain, reduce the risks associated with uncertain future market conditions, and create competitive pressure that drives down prices over time. Optionality allows policymakers to adapt as technologies mature, costs evolve, and demand fluctuates; helping ensure that the transition remains affordable and resilient rather than exposing households and industry to unnecessary financial risks.

At the same time, for CEE, building a homegrown, diversified energy system is not only a climate imperative but a national security one. Russia’s war in Ukraine, gas supply disruptions, and the geopolitics of critical minerals all highlight the vulnerabilities of relying too heavily on external suppliers. As a key geopolitical corridor linking Western Europe, the Black Sea, and the post-Soviet space, CEE is now at the centre of Europe’s energy security, which is why the region needs a resilient system that is diversified across technologies and supply chains, minimises single-point dependencies, can adapt to geopolitical shocks, and avoids extreme price volatility.

Part 3. The challenges and recommendations

Despite growing recognition of the need for a resilient clean energy portfolio, several barriers continue to impede progress.

- Political narratives need to remain aligned with voter priorities. Without messaging that connects climate solutions to economic and security outcomes, ambitious policies risk losing public support – especially when faced with the cost and disruption of change.

- Some policy frameworks still favour narrow technology pathways. Many CEE countries continue to rely on policy tools that incentivise specific technologies—often those with the lowest immediate cost—rather than building a balanced long-term system. This can lock countries into vulnerable positions, especially as systems evolve.

- Regulatory indecisiveness and financing structures create a hindrance for clean energy deployment. Long permitting timelines, limited access to finance for emerging technologies, and inconsistent regulatory frameworks create uncertainty and slow deployment. CEE voters are unconvinced about how to fund the energy transition. In 2025, only 55% felt any option was a good way to pay for it: 30% backed cutting other public services, 25% supported higher government borrowing, and 25% favoured businesses paying from their revenues even if prices rise. Overall, voters want the transition to be driven by better technology and lower costs, not by top-down mandates.

- Regional coordination remains insufficient. While CEE countries share common vulnerabilities and opportunities, cooperation on cross-border infrastructure, planning, and innovation remains limited. This fragments markets, inflates costs, and slows the adoption of solutions that require scale.

Conclusion: A call to action for a more resilient CEE energy future

The new data from Project Tempo offers a timely and essential reminder that the success of the energy transition in Central and Eastern Europe hinges on aligning climate ambition with the everyday concerns of voters and the strategic realities facing governments.

Policymakers in Central and Eastern Europe have a distinct opportunity to advance climate action framed through the lenses of economic resilience and security.

A technology-neutral, diversified energy portfolio will deliver reliability, strengthen industrial competitiveness, and enhance national security—all while reducing emissions. But unlocking this future requires political will, strategic communication, and policies designed for implementation as much as for ambition.

1 Countries included: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia