CATF: Poland’s NECP raises ambition, but its success depends on delivering clean firm power alongside renewables

Poland published its updated National Energy and Climate Plan. CATF’s initial assessment finds that although the plan shows progress, it still falls short of its potential to accelerate the deployment of clean energy technologies, with implications for Poland’s contribution to the EU’s 2030 targets and 2050 climate neutrality goal.

Why it matters

The NECP is Poland’s core planning document for meeting EU climate and energy targets and is intended to underpin the country’s Energy Policy to 2050. Its timing is critical, coming amid major geopolitical shifts and new EU industrial and energy initiatives, including the Clean Industrial Deal and the Action Plan for Affordable Energy Prices. Decisions taken now will shape Poland’s energy security, industrial competitiveness, and decarbonisation pathway for decades.

What’s in the plan

The updated NECP signals a shift away from coal toward a more diversified clean energy portfolio. In the ambitious WAM scenario, Poland targets a 65–68.9% share of renewables in electricity generation by 2040, driven mainly by wind, solar, and biomass. However achieving deep decarbonisation of the Polish electricity sector will depend not only on the development of renewable energy sources, but also on the deployment of nuclear energy. The estimated total gross electricity production from nuclear power plants (large-scale units and SMRs combined) in 2040 will amount to 44 TWh (ambitious scenario). By 2030, the plan raises the renewables share in gross final energy consumption to 32%, up from 30% in the previous plan, and projects a 52.7% economy-wide emissions reduction relative to 1990. While this represents a significant increase from the 23% reduction achieved in 2022, it still falls short of the EU’s 55% target.

What should be improved

While renewables will play a key role in decarbonising Poland’s grid, they alone cannot deliver all required emissions reductions. Deployment constraints, grid expansion needs, land use, supply chains, and critical mineral availability limit the pace of change, particularly for industrial decarbonisation. To maintain reliability and control costs, Poland will also need substantial amounts of clean firm power — always-available, zero-carbon capacity — alongside renewables.

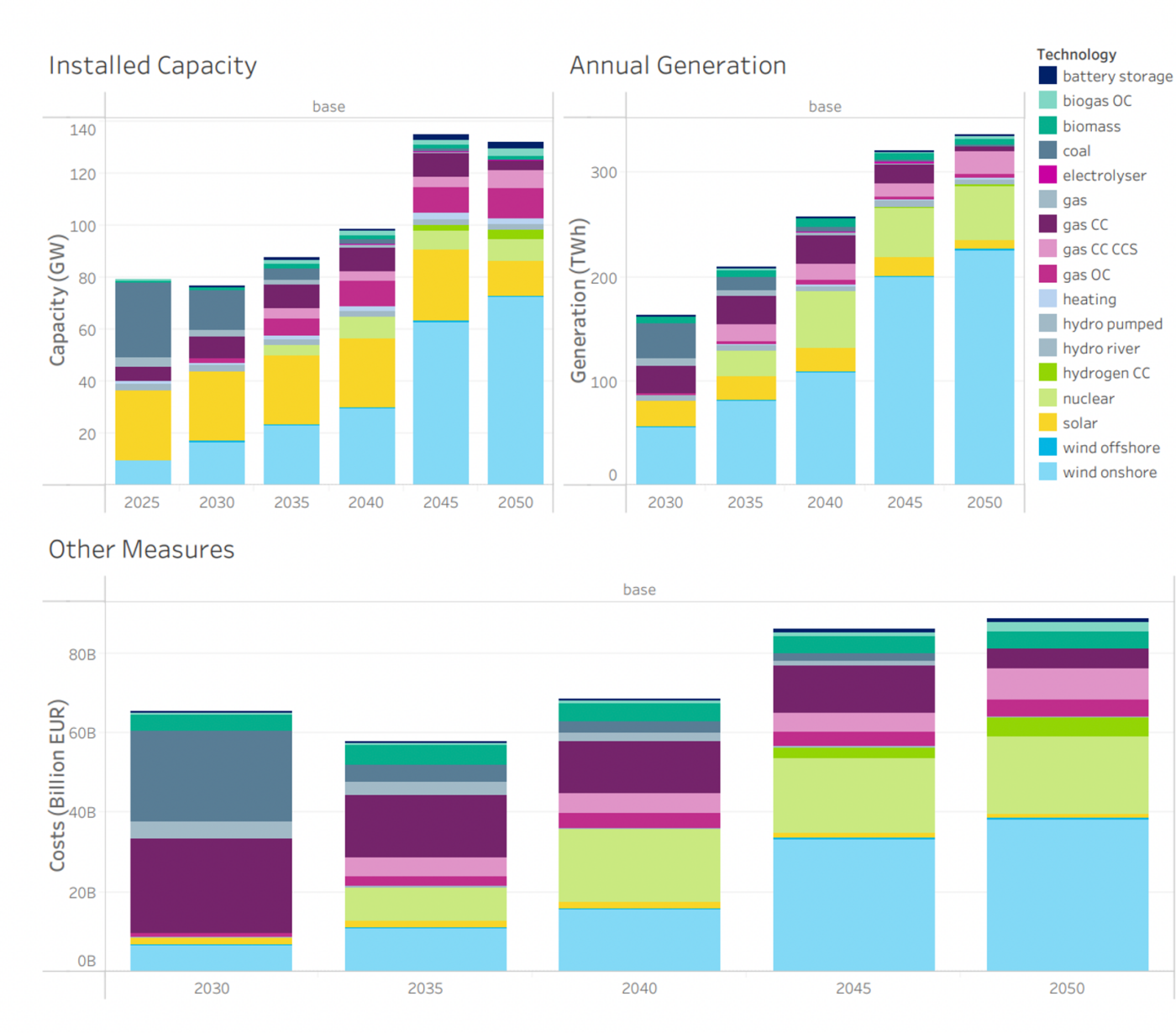

Figure 1: Base scenario, Decarbonising Poland’s Power System (CATF, 2024)

CATF analysis shows that technological optionality offers the most effective and competitive pathway, combining renewables with nuclear energy, storage, demand response, and biomass.

“ Maintaining technological optionality is essential to delivering a cost-effective and resilient energy transition. Poland’s NECP recognises the role of a broad portfolio of clean technologies, including nuclear, in the future energy mix,” said Bartłomiej Kupiec, Policy Consultant, Central and Eastern Europe at CATF.

Poland’s energy strategy must remain flexible in the face of uncertain technology costs, capital availability, and supply chains. “Regular reviews of technology choices and portfolio-level risk assessments will be essential to keep Poland on track to meet its climate and economic objectives,” Kupiec added.

Nuclear energy

The updated NECP presents an expanded role for nuclear energy in Poland’s future energy mix, indicating a projected installed capacity of 4.9 GW in the business-as-usual scenario and 5.9 GW in the ambitious scenario by 2040. Nuclear energy is positioned as a firm, dispatchable source of power alongside storage systems, which play a stabilising role in a system with a growing share of variable renewables. The document also references the potential role of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) and acknowledges their relevance for the long-term transition. At the same time, the projections do not distinguish between large-scale nuclear units and SMRs, which simplifies the overall outlook but leaves open questions about timelines, ownership and technology.

What should be improved?

Achieving 5.9 GW of nuclear capacity by 2040 requires a clear and actionable delivery pathway. This level of ambition implies that project development must progress rapidly, including advancing negotiations for the EPC contract for the first large-scale plant and taking decisive steps on the second plant (EJ2), such as identifying the project lead, selecting the technology and site, and formalising delivery arrangements. The NECP also mentions using nuclear reactor waste heat for district heating, but it does not clarify the technology or fraction of the heat capacity to be used for this process. Integrating such systems requires early design-stage planning to ensure compatibility with safety assessments and sufficient physical space for district heating infrastructure. The NECP does not address whether additional nuclear capacity may be required post-2040. Depending on market conditions and progress with deployment of other low-carbon technologies, there may be scope and, in some scenarios, a need for higher nuclear capacity by 2050, contingent on the performance and delivery track record of first and second nuclear power plants and potential early SMR deployment.

“While Poland’s updated NECP rightly identifies nuclear energy as a critical, firm backbone for its decarbonizing grid, the ambitious 5.9 GW target for 2040 remains a statement of intent rather than a guaranteed outcome. To succeed, the government must urgently translate this vision into an actionable, stepwise pathway—finalizing contracts for the first plant, launching the second without delay, and seriously planning for district heating integration from the outset. Without these concrete steps and a clear post-2040 perspective, the ambition risks being just a hopeful projection,” said Malwina Qvist, Director for Nuclear Energy at CATF.

Hydrogen

The updated NECP prioritises renewable hydrogen across a multitude of sectors: in industry as a decarbonised feedstock and fuel, identifying refining and fertiliser production as the primary sectors for deployment, as well in transforming transportation fuels and district heating. Hydrogen is also anticipated in the power sector, primarily to provide system flexibility in the form of dispatchable energy to grids powered by a high share of renewables. NECP projections indicate that renewable hydrogen production becomes significant only after 2035.

“Clean hydrogen is critical to decarbonising Poland’s economy, but success hinges on prioritising hard-to-abate industries and supporting multiple low-carbon production pathways within a clear national industrial decarbonisation strategy,” said Alex Carr, Deputy Director, Industrial Innovation, CATF

What can be improved on hydrogen?

Implementing a national clean hydrogen ecosystem will take time to build and scale. Initial deployment should therefore be targeted, particularly in its initial years, prioritising hard-to-abate sectors where electrification opportunities are limited or where hydrogen is an essential process input like in refining, fertiliser and chemicals production. The final draft NECP lacks a clear, data-driven assessment of how much clean hydrogen these sectors will actually need and how Poland plans to meet this demand through domestic renewable hydrogen production. Rather than setting production targets and relying on market allocation, policymakers should establish a framework that prioritises uses where hydrogen can deliver the greatest emissions reductions and in a cost-effective manner. This requires building a plan at the national level where hydrogen is integrated into wider industrial decarbonisation efforts. Within this, hydrogen production and infrastructure should be anchored around industrial needs. Deployment in other sectors, such as gas grid blending, residential heating, or light-duty transport, should be minimised or prohibited, particularly where other more efficient and cost-effective decarbonisation options are available.

Renewable hydrogen capacities face limitations in Poland due to the country’s carbon-intensive electricity grid and limited renewables, making it both very costly and intermittent in supply. Poland should therefore open up its ability to meet hydrogen demand through multiple low-carbon production pathways, including CCS-enabled hydrogen production, which offers the opportunity to align hydrogen with CCS developments particularly around industrial clusters.

Domestic production may be unlikely to meet total demand, Poland may need to consider an coherent import strategy but only where critical gaps to meeting demand emerge. Only the most technoeconomic import pathways should be considered and import distances should be minimised as much as possible.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS)

CATF welcomes that the updated NECP recognises that CCS will be required if Poland is to meet its climate targets. The updated NECP gives CCS a more visible place in the national decarbonisation framework than earlier drafts, outlining its possible contribution across key sectors.

The document identifies the industrial sector as the area with the strongest and most immediate potential for CCS deployment, reflecting the sector’s high emissions profile and limited availability of alternative decarbonisation options in the near and mid-term. The plan also indicates that CCS- and hydrogen-related flexibility options may become relevant after 2035. CCS is referenced for cement production (using cryogenic capture) alongside clinker reduction, and for lime production as a complementary option to fuel switching and partial electrification. In the chemical and petrochemical sectors, CCS is listed for ammonia production, soda ash and salt production, and petrochemical processes. In the metallurgical sector, CCS is mentioned for copper and zinc production as part of broader decarbonisation measures involving electrification, fuel switching, increased use of scrap and process-gas optimisation. The potential role of CCS in the decarbonisation of the power system is also included and notes that CCS could be applied to fossil-fuel power plants, biomass units, and biogas and biomethane installations, including BECCS. As shown by CATF’s modelling of decarbonisation pathways for the Polish power system, scenarios that include CCS-equipped power result in lower average electricity prices, compared to scenarios where it is excluded. Poland should begin to proactively identify power plants suitable for CCS and integrate their demand in their CCS infrastructure planning.

It is also positive that the NECP signals the intent to work on the regulatory changes necessary to enable CCS deployment in Poland, including a national carbon management strategy, changes to permitting laws in relation to onshore storage of CO2, as well as the introduction of measures targeted at the development and regulation of a Polish CO2 transport network.

“It is welcome that Poland includes the role for CCS in its NECP. However, without a dedicated national CCS strategy, and the accompanying regulations on CO2 transport and storage, developments in Poland remain effectively frozen, and Polish industry will lack a key decarbonisation option,” said Codie Rossi, Europe Policy Manager, Carbon Capture at CATF.

What can be improved on CCS

While the Polish Government’s intentions expressed in the NECP are welcome, the lack of timelines for their implementation will note give certainty to industry which will require CCS to decarbonise. CATF analysis has shown that the average costs for deploying CCS in the CEE region would be 40% lower if domestic storage resources are developed and available; an export-based model will effectively translate into a competitive disadvantage for CEE industry, compared to industry located around the storage sites in the North Sea. The NECP still lacks specific goals, timelines and steps to implement the regulatory and financial frameworks for CCS in the Polish industry. CCS will only be available as a decarbonisation option for Poland if the regulatory and policy environment both permits and enables deployment. Due to the timelines of project development, this may result in increased exposure to the ETS price for Polish emitters that will depend on CCS, particularly the countries’ cement sector.

While the NECP notes that cement will be a key sector for the development of CCS, the NECP takes a surprisingly prescriptive approach to capture technology for the sector, outlining one method (cryogenic capture). While the NECP does not rule out the deployment of other capture technologies, the NECP should leave technology choice open to a portfolio of solutions (such as amine or oxyfuel) that may better suit individual plant needs.

While the NECP acknowledges the EU’s Net-Zero Industry Act ‘s 50 Mt storage target (NZIA), the tone is sceptical. The plan expresses “serious doubts” regarding the feasibility of meeting the 2030 CO2 injection capacity targets, citing long lead times for storage development. To comply with the NZIA obligation and unlock the sector’s potential, the final plan must move from scepticism to action by setting a concrete timeline for a national CCS strategy and the necessary legal frameworks for storage operation. Poland should look to the NZIA and its obligation on Polish oil and gas producers as an opportunity to kickstart the CCS opportunity in the country.

The plan identifies the Innovation Fund as a support source but does not introduce a national carbon contracts for difference (CCfD) mechanism, which is essential to provide long-term revenue stability and enable CCS projects in hard-to-abate sectors to reach final investment decisions. Without clear targets, CO2 infrastructure planning and financing tools, Poland risks missing the opportunity to establish a coherent policy framework for CCS deployment.

The NECP also refers to plans for a national social education campaign to support public acceptance of low-carbon technologies, which is an important step. However, the document does not outline actions for the relevant ministry to develop practical guidance on early and structured community engagement around CCS projects. Establishing guidelines that require early-stage dialogue with local communities, including public meetings, and opportunities to provide feedback before permitting begins, would help ensure transparent communication and facilitate more informed and constructive participation. Such guidelines could help project developers and regional authorities build trust, address concerns proactively, and improve overall social readiness for CCS deployment.

What happens next

The Polish government has indicated that it aims to finalise the work on the NECP in January 2026. The European Commission will assess Poland’s plan as part of the EU-wide NECP review.

Background

National Energy and Climate Plans are the EU’s main tool for translating long-term climate ambition into near-term action. CATF analysis has consistently found that many NECPs fall short of bridging the gap between 2030 targets and the EU’s legally binding 2050 climate neutrality goal.

CATF’s scenario-based modelling of Poland’s power sector has shown that achieving climate neutrality by 2050 at manageable cost requires a significant role for nuclear energy alongside renewables, storage, and other clean technologies. The analysis finds that limiting nuclear or other clean firm power options increases system costs, infrastructure needs, and delivery risk.

CATF has previously called on Member States to use NECP revisions to close this planning gap by strengthening coordination, improving implementation and accountability, and keeping multiple technology options on the table to manage transition risks. In its flagship report, Bridging the Planning Gap, CATF stresses that credible plans must show how today’s policies and investments prepare energy systems for full decarbonisation.

To support this process, CATF has published a series of NECP playbooks that provide practical guidance on integrating key technologies and policy approaches into national plans, including carbon capture and storage, clean hydrogen, methane mitigation, nuclear small modular reactors, and superhot rock energy. Together, these resources aim to help Member States develop more robust, flexible, and future-proof NECPs aligned with EU climate and energy objectives.

Press Contact

Julia Kislitsyna, Communications Manager, Europe, [email protected], +49 151 16220453

About Clean Air Task Force

Clean Air Task Force (CATF) is a global nonprofit organisation working to safeguard against the worst impacts of climate change by catalysing the rapid development and deployment of low-carbon energy and other climate-protecting technologies. With more than 25 years of internationally recognised expertise on climate policy and a fierce commitment to exploring all potential solutions, CATF is a pragmatic, non-ideological advocacy group with the bold ideas needed to address climate change. CATF has offices in Boston, Washington D.C., and Brussels, with staff working virtually around the world. Visit catf.us and follow @cleanaircatf.