Aligning Africa’s climate ambition with development realities

The adoption of the Paris Agreement marked a landmark moment for global climate diplomacy. This year marks the 10-year anniversary of that historic agreement, when 195 countries came to unanimous agreement to adopt a legally binding climate treaty with the goal of keeping the global average temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. Central to implementing the Paris Agreement are national climate action plans known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), through which countries articulate their national strategies for mitigating and adapting to the impacts of climate change, with updates every five years.

A non-mandatory and complementary plan, the Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emissions Development Strategy, was intended to situate these commitments within the broader context of countries’ long-term development plans. The first round of NDCs were submitted in 2015 as intended nationally determined contributions, followed by updates and new submissions in 2020/21. The next round of submissions was due by September 2025, but at this time of writing, only 61 countries (representing 31% of global emissions) have submitted new NDCs, leaving 136 Parties who have yet to do so.

This uneven pace of submissions reflects broader challenges in translating international climate commitments into nationally owned and actionable strategies—a dynamic that is particularly evident in the African context. To better understand these dynamics, Clean Air Task Force (CATF) conducted a comprehensive analysis comparing African countries’ NDCs with their National Development Plans (NDPs). The study assesses how well these two frameworks align—or fail to align—at a moment when countries must confront development realities alongside escalating climate pressures. This policy brief highlights key findings from that analysis and explores their national, regional, and global implications as countries continue to update their NDCs at COP30 and beyond.

Implementing NDCs in Africa

While NDCs have served as important blueprints for national level climate action, they have so far fallen short of bending the emissions curve downwards and positioning countries to better adapt to the impacts of climate change. The recent Global Stocktake— a mandatory periodic evaluation of progress under the Paris Agreement— found that Parties are not on track to meet their long-term goals and called for a significant step-up in ambition.

In many African countries, implementation of NDC targets has been constrained by financial, technological, and institutional capacity limitations that reflect broader development challenges. While climate change remains a global priority, African countries are simultaneously addressing pressing development concerns: access to modern energy services, improving education and health outcomes, ensuring food and water security, and closing infrastructure gaps. Achieving climate goals in this context requires integrating climate ambition with these development imperatives, rather than treating them as separate agenda items.

As countries mark the anniversary of the Paris Agreement and prepare the next round of NDC updates at COP30, this question becomes more urgent: to what extent have African countries managed to align climate ambition with their development priorities— and what must change to prevent further misalignment?

The climate-development policy divergence

The study finds significant divergence between climate and development policy in Africa. NDCs and NDPs are arguably developed for entirely different purposes: NDCs are designed to shape climate action, while NDPs guide national development priorities. However, climate and development issues in Africa are deeply intertwined, with many synergies and trade-offs.

A recently published CATF study reveals that achieving net-zero targets by 2050 comes with economic costs and could result in significant impacts on land, food, and water systems. These potential system-level impacts of energy system transitions in Africa signal the need for climate action to be well-coordinated with other sectoral priorities. This need becomes even more acute when assessed against the continent’s vast development challenges and rapidly shifting demographics. As the fastest growing continent, Africa will account for 25% of the global population by 2050— up from 19% today. This explosive population growth will drive greater demand for energy, food, water, infrastructure, and basic social needs.

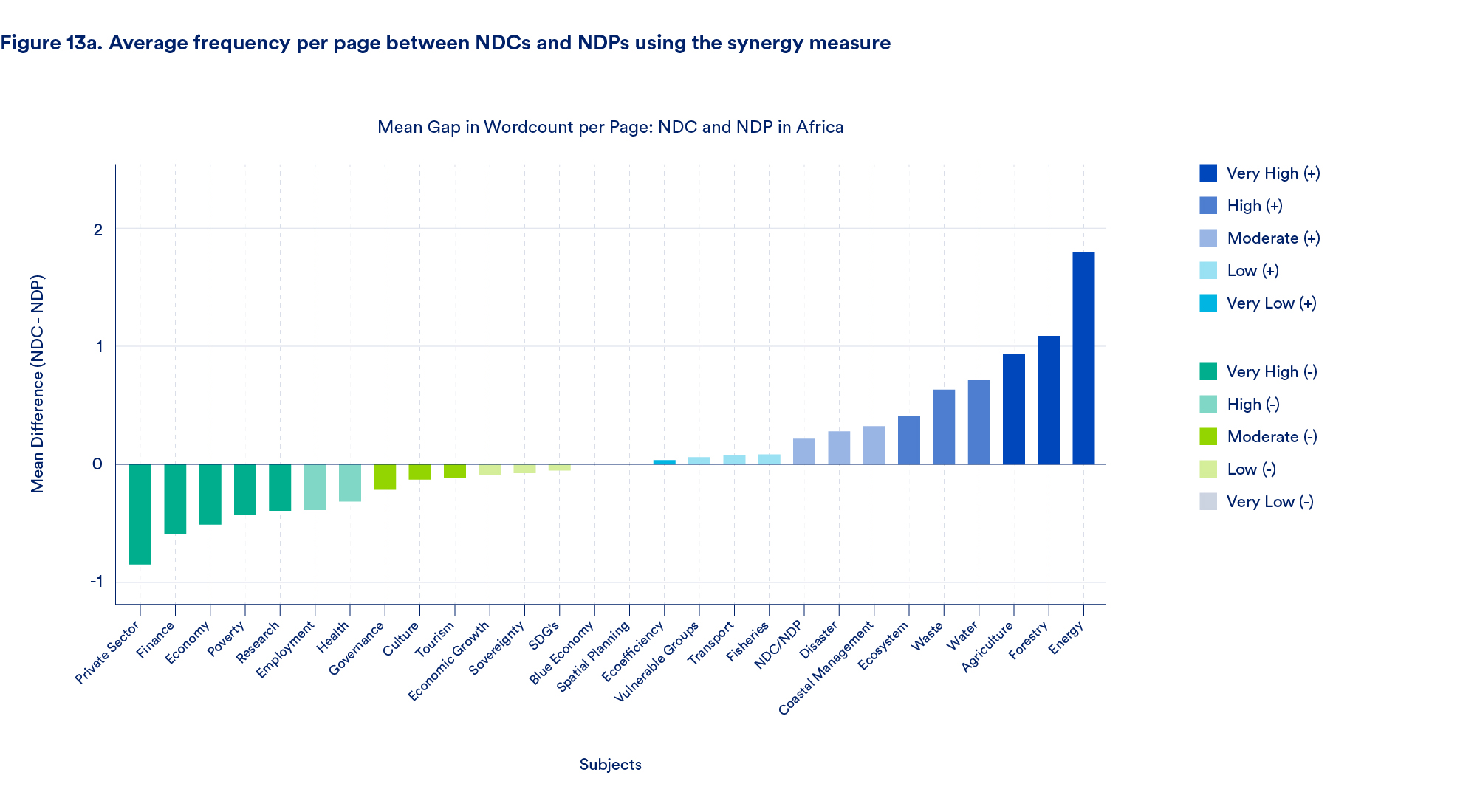

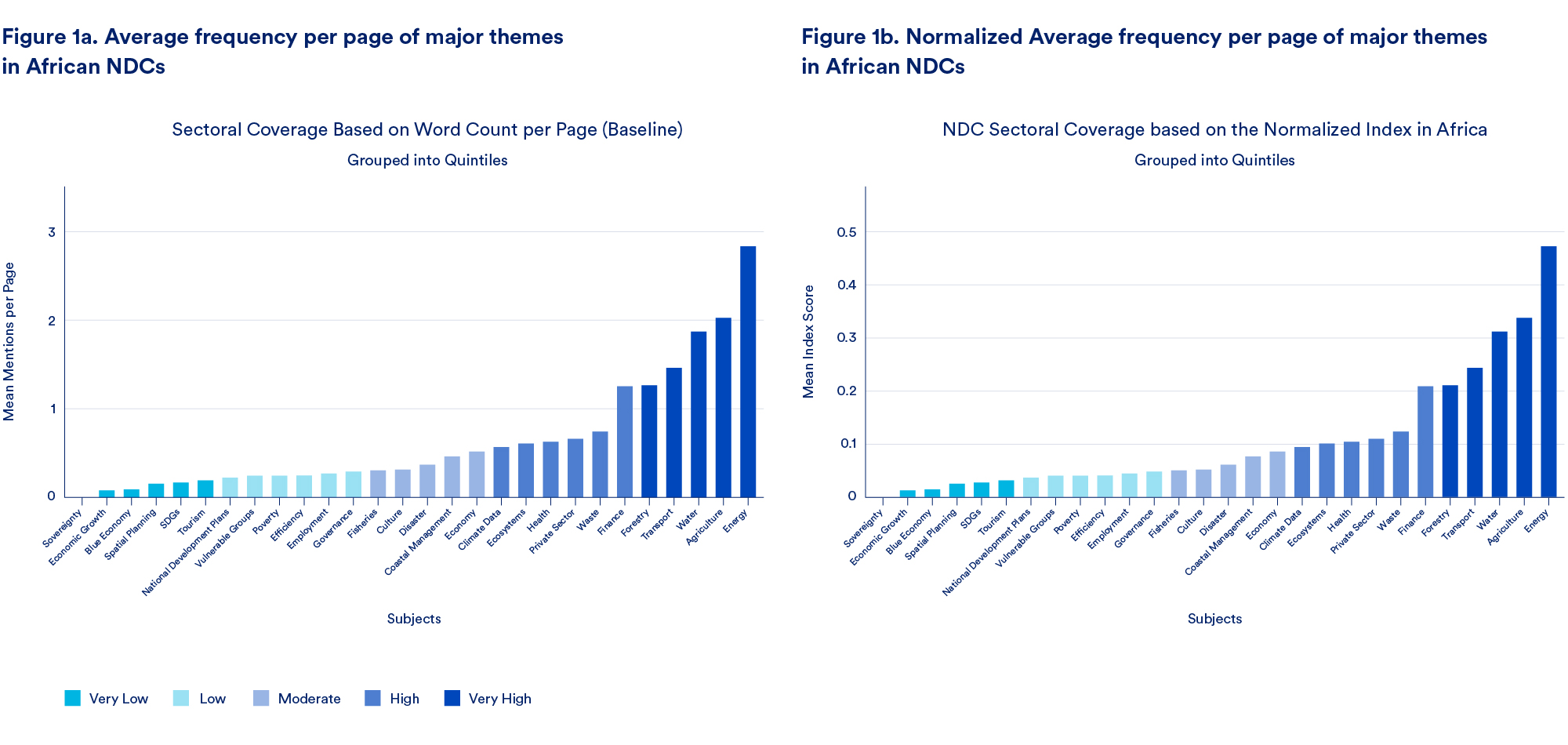

Our review of NDCs and NDPs in Africa suggests that governments may not be taking this holistic view of the climate-development nexus into account when designing climate strategies or development plans. Issues which are identified as critical to climate adaptation and mitigation— energy, agriculture, transport, water and forestry— tend to dominate NDCs, while NDPs emphasize themes such as private sector engagement, finance, economy, poverty alleviation. This divergence in policy focus implies that ambitious goals to transform energy systems, as articulated in NDCs, may not be effectively mainstreamed into national economic development planning and investment strategies. This raises serious questions about the feasibility of implementing these strategies, particularly regarding the financing and infrastructural requirements of climate action. Likewise, the economic impacts of climate action may be misunderstood, leading to climate investments that compromise, rather than promote development priorities.

While countries have been encouraged to develop Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emissions Development Strategies to situate their NDCs within the broader context of their long-term development plans, this requirement is not mandatory, and very few countries have undertaken this exercise.

The NDC-NDP policy divergence also has major financial implications. The Paris Agreement specifies the need for developed countries to provide the financial support developing countries need to implement climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, but progress has been slow. According to the High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, developing countries (excluding China) will need to mobilize $2.7 trillion annually to meet climate and other nature related goals. $1.3 trillion of this is expected to come from international sources, and $1.4 trillion from domestic sources. The 2024 African Economic Outlook projects even higher climate finance requirements for the African continent alone at $2.7 trillion by 2030. Africa’s climate finance requirements are almost at par with the continental GDP and far exceed its debt levels, which currently stand at $1.8 trillion, with a median debt-to-GDP ratio of 65.5%.

These domestic fiscal challenges, coupled with the failure of multilateral climate diplomacy to raise the needed international finance for climate action, create deep conflicts in resource prioritization for African countries which also face competing development priorities. Misaligned climate and development planning will only deepen this conflict, challenging the feasibility of both climate and development objectives and, in some cases, deepening development constraints.

The sectoral dominance of energy in African climate strategies

Energy is the predominant sector of focus in African NDCs.

This dominant focus on energy is consistent with the global focus on energy sector decarbonization as a key lever for reducing emissions. Climate mitigation accounts for up 66% of total climate finance needs articulated in the NDCs of African countries, with four sectors driving most of this demand: transportation, energy, industry, and agriculture, forestry and land use (AFOLU). Notably, AFOLU, Africa’s biggest emitting sector, accounted for only 7% of the total mitigation needs articulated in NDCs ($108 million), with the bulk of mitigation finance concentrated in the transportation and energy sectors. Over 94% of transportation finance needs are allocated to South Africa alone, while energy finance is distributed across renewable energy (88%), energy efficiency (10%), and crosscutting initiatives (2%). The relatively low ranking of AFOLU in climate mitigation finance could indicate two possibilities: (1) Africa’s mitigation priorities may be misaligned, or (2) mitigation measures in AFOLU may be cheaper than those in the energy and transport sectors. Regardless of which of these reasons hold, the AFOLU sector warrants deeper investigation, as it is also critically important for adaptation due to its high vulnerability to seasonal climate variability.

Energy, agriculture, and the future of employment in Africa

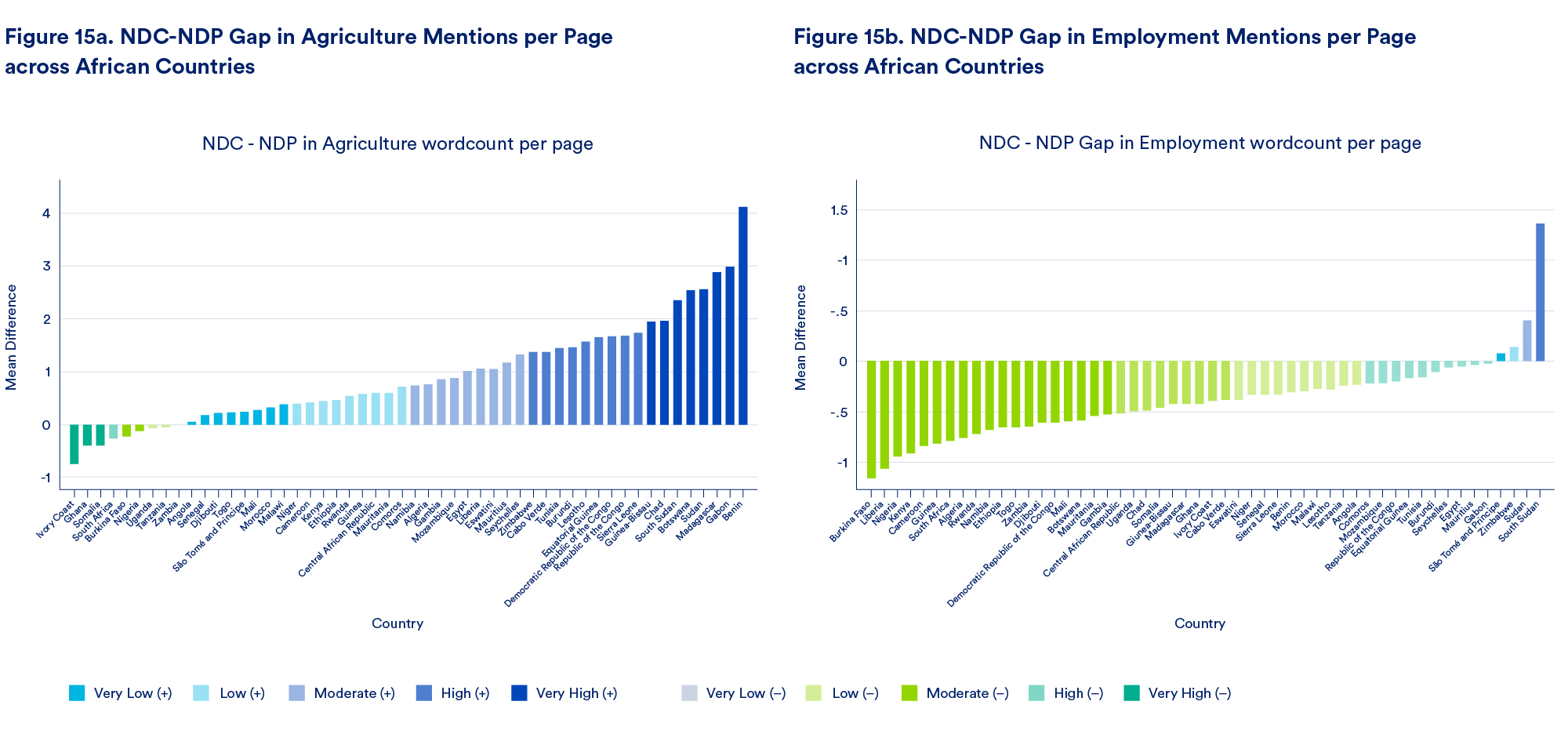

The AFOLU sector is noteworthy for its dual relevance to energy sector decarbonization and the African economy. The agricultural sector employs roughly 60% of Africa’s total workforce and remains the primary source of employment in some of the continent’s most populous countries.

| Rank | Country | Number Employed (Million) | Population (Million) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethiopia | 36.2 | 132.5 |

| 2 | Nigeria | 26.8 | 232 |

| 3 | Tanzania | 19.2 | 66.6 |

| 4 | Democratic Republic of Congo | 18.6 | 109.2 |

| 5 | Uganda | 11.7 | 50.0 |

| 6 | Madagascar | 10.5 | 31.9 |

| 7 | Mozambique | 9.9 | 34.6 |

| 8 | Kenya | 7.6 | 55.3 |

| 9 | Egypt | 5.7 | 116.5 |

| 10 | Ghana | 5.5 | 34.4 |

Energy sector transformation, particularly the shift to renewables, is a key mitigation strategy in African NDCs. However, this transition could potentially come at a cost to the continent’s critical agricultural economy. CATF modeling of net-zero scenarios in Africa finds that achieving net-zero by 2050 in Africa will require a rapid shift to renewables— wind, solar, and hydro— alongside carbon removal technologies like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). While emissions would fall below zero by 2050, this aggressive energy system transformation would place additional pressure on water resources and reduce cropland availability by 31%, driving up staple food prices. The potential land-use impacts of Africa’s energy transition could negatively affect the agricultural sector and associated employment. Yet, our assessment of African NDCs suggests this externality is not fully considered in climate planning. Employment is generally not a priority in NDCs— even in countries where economies are heavily dependent on agriculture for jobs.

Changing course

This analysis reveals that while linkages between climate and development may be recognized in theory, they remain disjointed in practice. This is not entirely surprising— climate discourse has largely evolved separately from economic development discourse. Yet in contexts like Africa, the climate-development linkage cannot be side-stepped. The ability to finance the full scope of climate action will require significant domestic capital, which is scarce in low-income economies. On the other hand, the rapid transformation of energy systems can threaten development imperatives and deepen competition for resources that are central to the structural transformation of African economies. This reality calls for a new approach to climate diplomacy, one which recognizes development as a key determinant of feasible climate action— and vice versa.

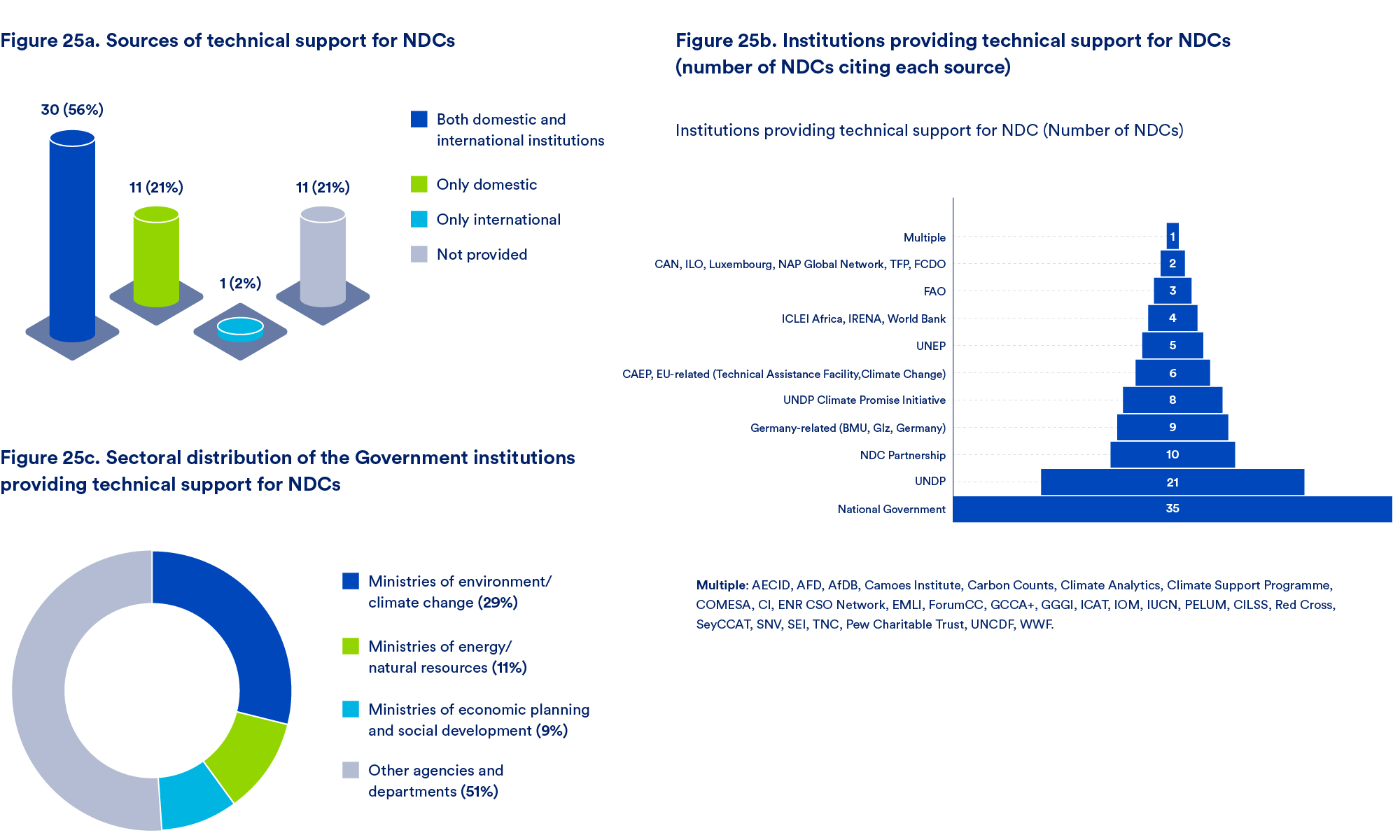

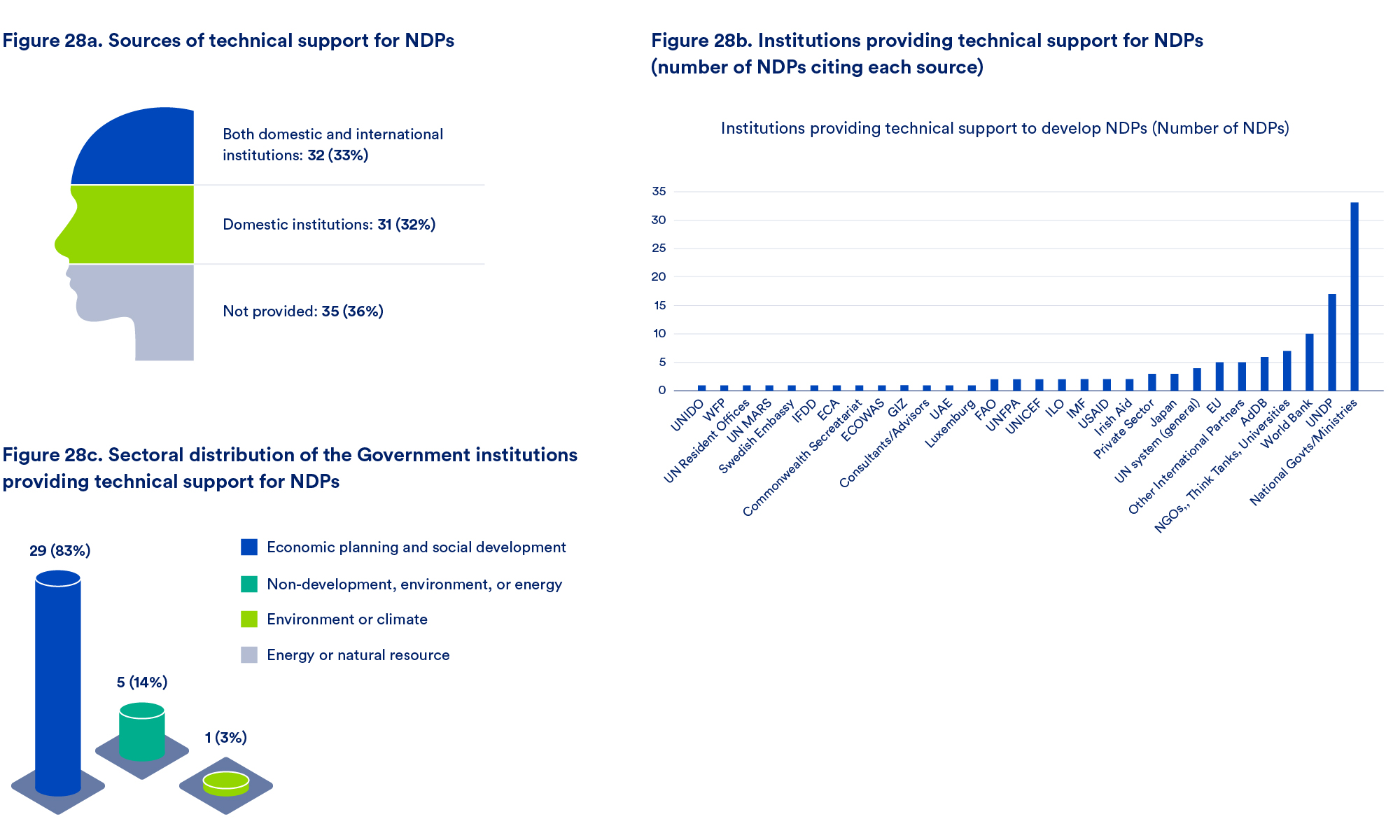

Several shifts are needed to change course. At the national level, governments need to better coordinate climate and development planning. NDCs are typically developed under ministries of environment, climate change, energy, or natural resources, while NDPs are typically led by ministries of economic planning and social development, often with little to no input from the environment or natural resources sectors.

Greater coordination across the environment and development ministries would help ensure that the tradeoffs between climate action and development are well understood and integrated into national level strategies.

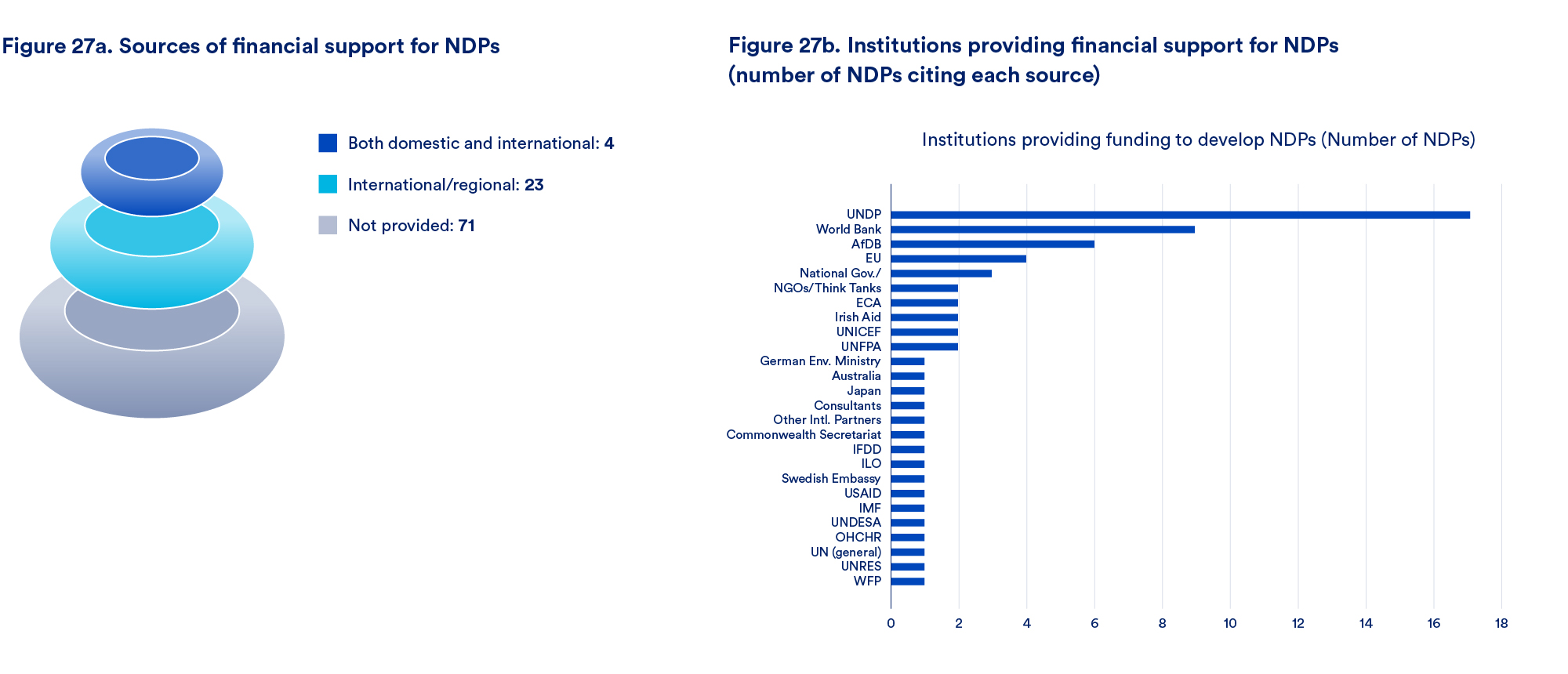

Both NDCs and NDPs rely on external funding and technical assistance from international sources. In providing external support multilateral and bilateral partners must prioritize local context and the real trade-offs and synergies between climate and development, rather than imposing externally derived frameworks that may not reflect African realities.

Ultimately, global climate diplomacy must better reflect the reality that climate action in Africa is as much about development as it is about reducing emissions. African governments should incorporate this perspective into negotiations on the global stage. National governments and regional institutions like the African Union must invest in building a robust, data-driven understanding of the domestic trade-offs and opportunities of the climate-development complex. These insights can then shape Africa’s bargaining position in global climate diplomacy, promoting formal ambitions assessed not only by emissions reduction potential but also by metrics for energy access, food security, and poverty reduction. Multilateral support negotiations can also shift from non-binding pledges toward demands for deeper structural changes that provide the financial, institutional, and technological conditions necessary to meet both climate and development imperatives.

To make meaningful progress on climate action, development, and climate finance at COP30, both developing and developed nations will need to recognize and account for these interconnected realities at the negotiating table.