Next steps for Article 23: How penalties can give teeth to the European Union’s CO2 storage obligation on oil and gas producers

In 2024, the EU broke new ground by requiring oil and gas producers to start building the CO₂ storage infrastructure needed to reach its climate goals. Under the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), these companies must deliver 50 million tonnes of annual CO2 injection capacity by 2030 — a target critical to keeping industrial decarbonisation on track. Analysis by the Clean Air Task Force shows some international oil companies are well prepared, while several regional operators face steep shortfalls. With national governments now tasked with setting penalties by July 2026, the next two years will determine whether this landmark law drives real investment or risks uneven progress across the EU.

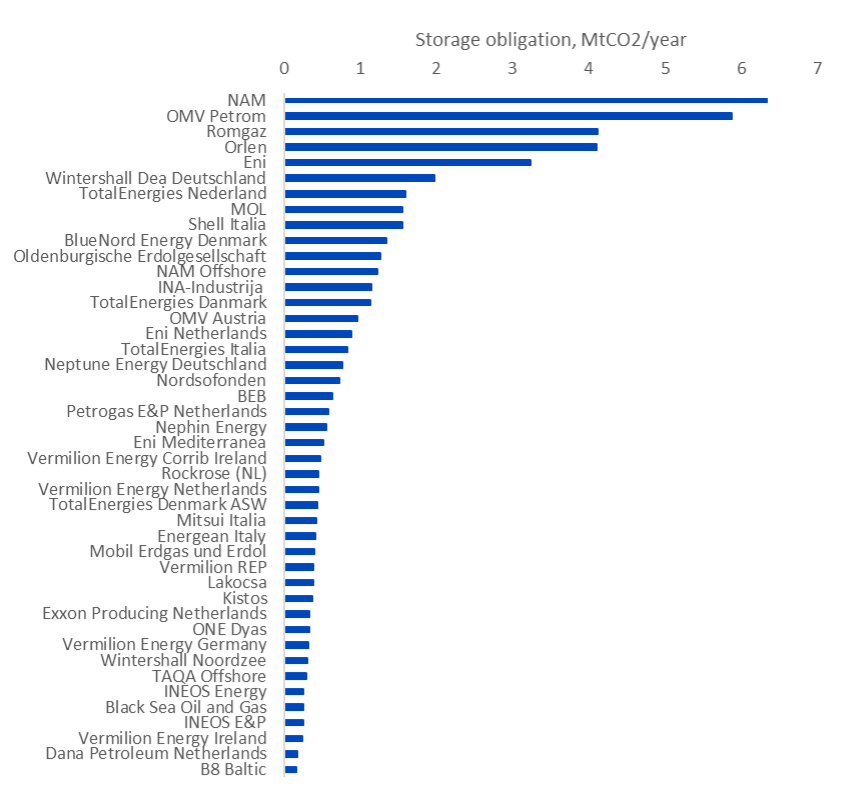

The past few months have seen some major milestones in the implementation of the carbon capture and storage requirements of the NZIA, including the European Commission’s Decision identifying the contributions of the obligated producers. As stipulated under Article 23 of the regulation, these contributions are allocated to holders of production licences in proportion to the share of oil and gas they produced between 2020 and 2023. The Decision identifies 44 obligated entities which produced oil or gas in the EU over the relevant period, and excludes smaller producers which collectively contributed 5% of the total volume (see Figure).[1]

Figure 1. The CO2 storage capacity obligations of all 44 licence-holding entities identified by the European Commission.

Are oil and gas producers on track to meet their obligations?

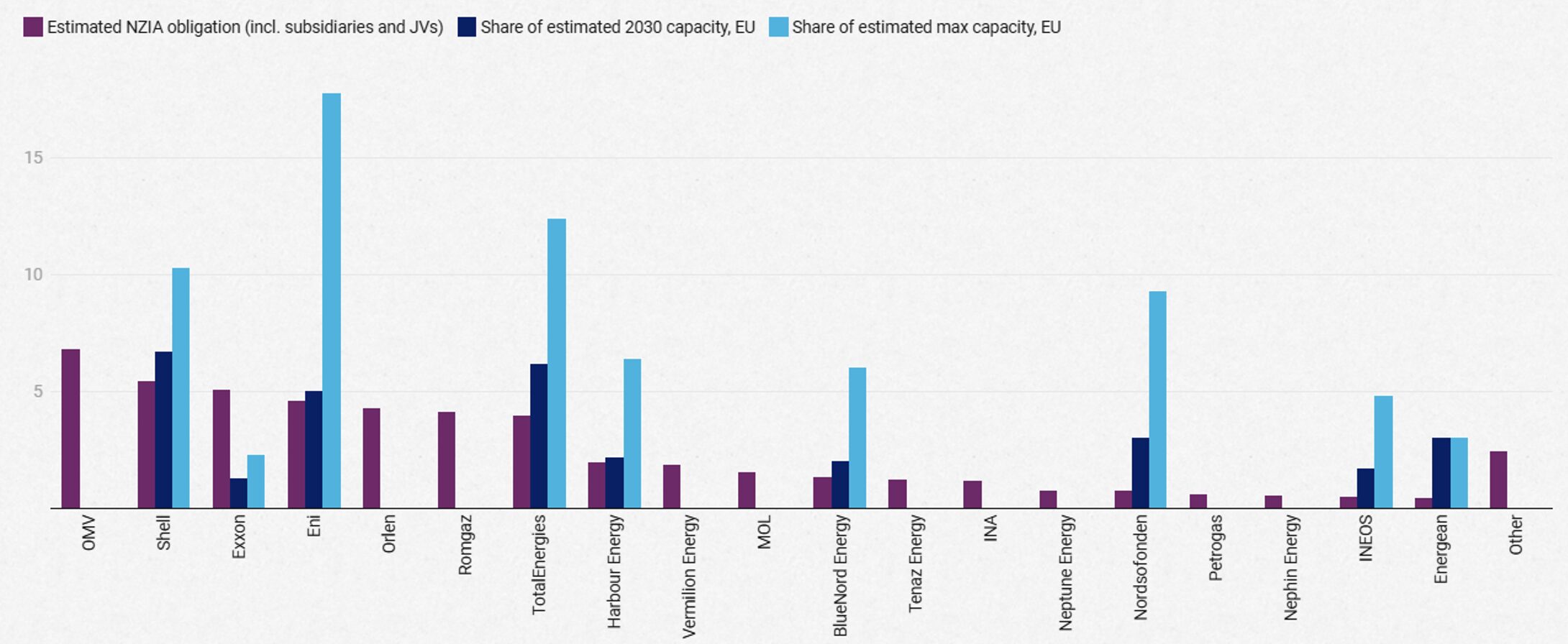

Following the publication of the Commission’s Decision, CATF’s CO2 storage tracker has featured our analysis of how the company obligations compare with the storage capacity they currently have under development. As many of the obligated entities are joint ventures or local subsidiaries, it is useful to rationalise the list into parent companies (Figure 2). These entities, which include international oil majors such as Shell, Exxon, and TotalEnergies, as well as regional producers with significant state ownership, will be functionally responsible for delivering on the storage obligation. While our analysis has partitioned the obligations of joint ventures according to ownership stakes, in reality the partners may reach different agreements on how they collectively meet the target capacity.

Figure 2. Estimated scale of company obligations under Article 23 of the NZIA and corresponding shares of planned storage capacity in the EU

Over 80% of the 50 Mt/year target is to be delivered by just 12 companies, and around half of the target by only five companies. Should their current storage projects progress according to announced schedules, Shell, Eni, and TotalEnergies are on track to meet their obligations, with the potential to expand further beyond 2030.[2] In contrast, national oil and gas companies in Romania (OMV Petrom and Romgaz) and Poland (Orlen) are in a challenging position, with significant obligations but little or no announced capacity under development in the EU. The regulation has noticeably accelerated activity within these companies and fortunately both countries offer promising geology for CO2 storage. Orlen are investigating potential CO2 storage sites in central Poland and offshore, while OMV Petrom have recently begun exploring a storage site near Botesti.

The companies are not required to satisfy their obligation alone; the regulation allows them to reach agreements between themselves or with other storage developers, providing some flexibility to those entities currently facing a shortfall. The CATF storage tracker identifies potential for another 5 Mt/year of capacity that could feasibly be operational by 2030, which is under development by non-obligated entities. As can be seen in Figure 2, there are also obligated entities which may have surplus capacity in 2030, such as Nordsøfonden in Denmark and Energean in Greece (through its CO2 storage-focused subsidiary Enearth).

In June, the producers were required to submit plans to the Commission detailing how they intend to meet their respective targets – these have not been publicly released. However, starting from June 2026, they will need to submit annual progress reports which will be made public by the Commission..

Next steps to deliver on the target: Effective penalties and Member State support

What remains to be done to ensure the storage target is met on schedule? By 30 June 2026, Member States are required to establish penalties for any infringements of the obligation – a provision which was one of several amendments proposed by CATF and Article 23 Project partners during the NZIA’s consultation process. Penalties can be on an administrative or legal basis and must be ‘effective, proportionate and dissuasive’ (a standard wording in EU law). Effective penalties will be essential to ensuring the obligated producers progress their storage plans in good faith, at the pace required, and dedicating appropriate financial resources.

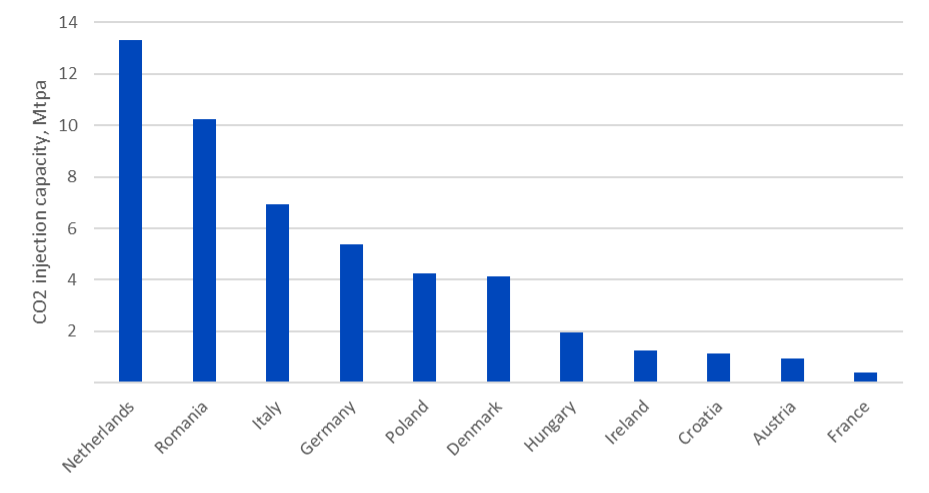

Compared to some other environmental legislation in the EU, the legislative text offers relatively little guidance on how penalties should be designed. There is therefore potential for significant divergence between Member States and a risk of slower progress by some companies and a disparity in the options available to decarbonising industries. Although obligated entities are not required to develop CO2 storage in the same region as their production activities, they will be subject to penalties according to the Member State in which they are registered. As shown in Figure 3, companies based in the Netherlands, Romania, Italy and Germany represent the majority of the obligation, so penalty design in these jurisdictions will have the most impact on the success of the regulation.

Figure 3. Article 23 obligations according to country of origin of the obligated company

Environmental penalties regimes in the EU have been designed in various ways, and can include administrative fines, periodic penalty payments, and criminal penalties enforced through national courts. Administrative fines are likely to form a key part of penalty design under Article 23, and must be set at a level which effectively deters companies preferring to pay the fine than invest in storage. Fines are typically linked either to the environmental cost, such as the carbon price under the ETS, or the cost of compliance. For example, ReFuel Aviation, which requires aviation fuel suppliers to provide a growing proportion of sustainable aviation fuel, includes penalties for shortfalls of at least twice the cost difference between conventional and synthetic aviation fuel.

For Article 23, penalties could be linked to the volume of ‘unstored’ CO2 emissions and an appropriate carbon price level. Germany has already taken a step in this direction in a draft amendment to its Carbon Dioxide Storage Act, which proposes that injection capacity shortfalls are fined up to the level of the penalties associated with failure to surrender ETS allowances. Assuming the current penalty level for ETS non-compliance (around €130/t) or at a projected ETS price for 2030[3], these fines could clearly become very substantial, reaching over a hundred million euros for every Mt/year of shortfall. Fines on this scale are unusual – if not unprecedented – in the EU and, while they would represent less than 1% of the annual revenue of the international oil majors, they would be much more significant for regional players like Romgaz. The upfront cost of delivering a storage project at the million tonne scale could easily be on this order of magnitude for offshore storage developments, while onshore sites may be significantly cheaper.[4] Storage project developers are expected to make a reasonable return on their investment by charging the industries which use the infrastructure, so any estimate of compliance ‘cost’ may need to reflect this return relative to the value of alternative investment in oil and gas production.

Strong penalties must also be accompanied by support from Member State governments for storage developers. First-mover countries like Denmark and the Netherlands have well-established procedures for awarding CO2 storage exploration licences and permits, supported by adequately resourced government departments and permitting agencies. In comparison, Poland, Romania and Germany must still put in place some of the procedures, regulations and institutional expertise that will allow their obligated entities to develop capacity within their own areas of operation, rather than buying into projects in other countries. Easy access to geological data also appears to remain a challenge in some Member States, despite provisions within the NZIA to ensure better data sharing. Enabling this greater regional diversity is vital to ensuring the obligation supports the decarbonisation needs of industrial emitters across the EU.

CATF project tracking determines the 50 Mt target is challenging to meet by 2030 under the announced schedule for planned projects, but the obligation should lead to accelerated deployment and new projects. To maintain ambitious deployment timelines, penalties will need to provide a real disincentive to delaying investment, without negatively impacting the ability of smaller entities to deliver on their obligation when they are actively progressing projects. Project deployment will necessarily be subject to timelines dictated by permitting authorities and local engagement strategies. Penalty designs should therefore consider allowing for such mitigating circumstances where developers are demonstrably acting at pace and with appropriate investment, particularly if shortfalls can be recouped once a project is operational. Obtaining exploration licences and initiating applications for full storage permits could be considered a prerequisite for obligated entities to demonstrate reasonable effort, but would need to be backed by real resources and other steps to advance the project.

However, companies should also be expected to build contingency into their plans by exploring a range of possible storage sites. Penalties can be increased under aggravating circumstances, for example, where companies are deemed particularly negligent, untransparent, or uncooperative, and repeated where companies fail to address shortfalls.

As part of a joint initiative with Carbon Balance and Bellona Europa, CATF will continue to track progress and compliance with Article 23, through the live storage tracker, annual reports, and regular policy briefs.

[1] Notably, several of the exempt entities listed in the Commission Decision are subsidiaries of other obligated entities, including Wintershall Dea International, Vermilion Hungary, and Energean Oil and Gas.

[2] Allocation of planned storage capacity to these entities assumes that storage projects developed by joint ventures are divided by ownership share. Shares of capacity belonging to non-obligated entities (e.g. Snam (Ravenna) and EBN (Aramis storage sites)) are partitioned among the obligated partners.

[3] https://www.simon-kucher.com/en/insights/carbon-costs-are-coming-ready-or-not. Projections for EU ETS I in 2030 range from €70 to €149 per tonne.

[4] The operational Northern Lights transport and storage project in Norway cost approximately €700 million for an offshore site with the capacity to store 1.5 Mt/year. However, Danube Removals is an onshore storage project planned in Hungary which has estimated capital costs of €80 million for storage, compression and pipeline transport of 0.5 Mt/year.