California’s transmission permitting: Slowest in the West?

This blog was co-authored by Sam Uden, Director of Climate and Energy Policy at Conservation Strategy Group.

California has established ambitious climate goals, including 90% zero-carbon electricity supply to retail customers by 2035 and 100% by 2045 as well as 100% light-duty zero-emission vehicles sales by 2035. A rapid expansion in transmission is key to unlocking the enormous amount of new and distributed clean energy resources required to achieve these goals. However, it currently takes over a decade to build new transmission projects in California. Without reducing these lead times, it is highly unlikely that California will be able to deliver on its world-leading climate ambitions.

There are two main drivers behind California’s sluggish transmission deployment. First is the time delay between when the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) approves a transmission project, and when an investor-owned utility submits its permit application to the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). Second is the CPUC’s own permitting process, including the time it takes to approve the Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity (CPCN).

In this post, we focus on the second driver. We compare California’s own CPCN process to that of other Western states, including time to approval and the availability of expedited review. We then look beyond the West, comparing California’s transmission permitting requirements to those of New York and Texas. We conclude by highlighting some promising California legislative efforts designed to improve permitting efficiency.

The transmission slowdown in California

Transmission permitting processes in California are lengthy and complex. A recent report by Clean Air Task Force, Transmission Development in California – What’s the Slowdown? describes the transmission project approval process in detail, including the phases of project development, trends from past and ongoing projects, and timelines for projects approved by CAISO. The report finds that major projects frequently take a decade or more before beginning construction and permitting them requires extensive coordination between CAISO, the CPUC, and utilities. According to the report, “long timelines and crippling delays continue to challenge current and future build rates.” CATF recommends revisions to the current planning and permitting processes in order for California to more rapidly authorize new transmission capacity, to connect new clean generation to the grid, and meet its clean energy and climate goals. Separate stakeholder analyses and articles have arrived at similar findings about the slow pace of California’s transmission permitting processes.

California Transmission Development Takes Longer than Anticipated

Other Western states are quicker on the draw

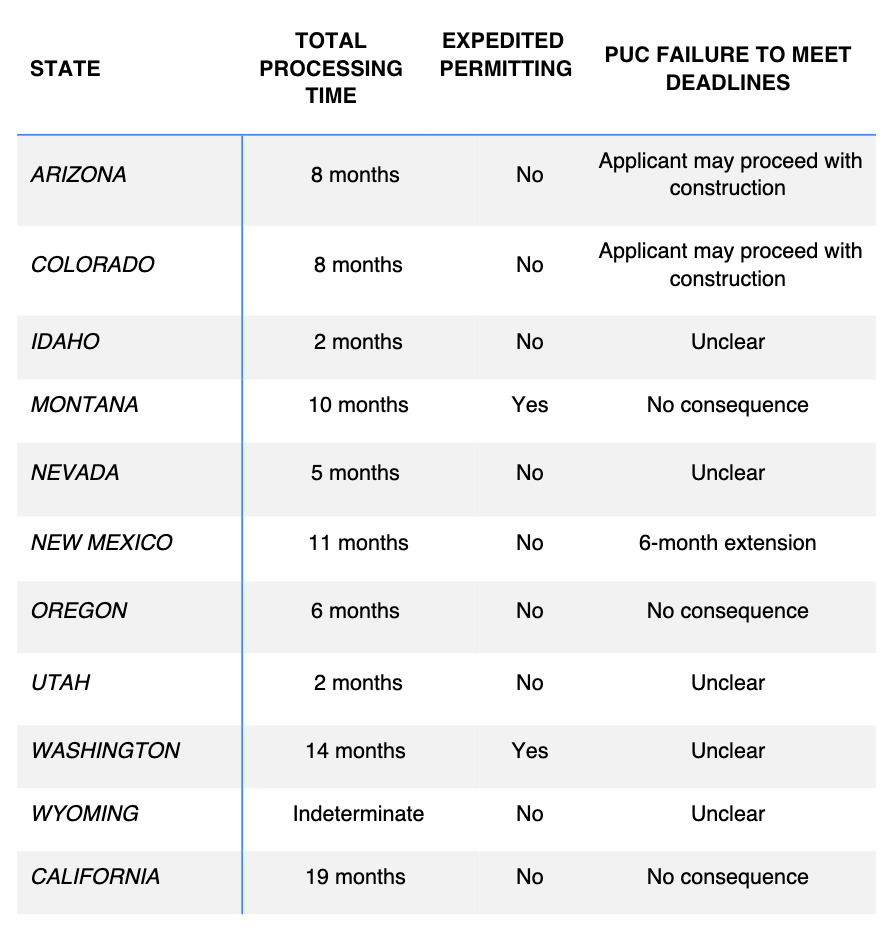

We reviewed and collated transmission project approval timelines from ten western states, including California. The perspective of western states is relevant because they neighbor California and share energy resources across borders but are not governed by a centralized grid planner like the CAISO. We surveyed states’ project size thresholds for requiring state regulatory approval, statutory and reported timeframes for processing transmission siting permits, and the statutory and reported timelines for the PUC or siting authority to make a final permitting decision – the last step in the process for project approval.

In our review of transmission project approval timelines, the CPUC’s 19-month timeline was the longest duration of any of the Western states for reaching a final decision on a CPCN. California’s timeline is almost one year longer than what a developer would expect in Colorado and New Mexico – two states that also have ambitious climate goals. California’s statute allows 5 additional months for this decision-making than that of the next slowest state, Washington, which in contrast to California has a process to expedite the review of priority transmission projects. Additionally, the CPUC can exceed its statutory timeline and delay a project permitting decision indefinitely. In other states, such as Arizona and Colorado, the PUC’s failure to meet its deadline results in automatic project approval and the issuance of a permit. Overall, and despite some data gaps, it appears that California has the slowest transmission permitting in the West.

Western State CPCN Statutory and Reported Permitting Timelines

How California stacks up against New York and Texas

Looking beyond the West, we compared California’s CPCN transmission permitting to New York and Texas. Those states are similar to California in that they are heavily populated, have single-state grid planners and market operators like the CAISO (NYISO and ERCOT) that are responsible for transmission planning, and have PUC processes as well.

We found that, like in California, in each case a PUC must approve or deny a transmission project’s application for a CPCN. We also found that all three states’ PUCs generally review the following elements: necessity of the proposed project, potential environmental and cultural concerns, right-of-way utilization, and methods used for construction.

However, our research found that only California requires an evaluation of a “no-project alternative” for an applicant to receive a CPCN. Specifically, California requires the CPUC to consider “The availability of cost-effective alternatives to transmission, such as energy efficiency measures and distributed generation.” This requirement largely duplicates a similar determination made by the CAISO and is in addition to the CPUC’s environmental reviews under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This “no-project alternative” is required even though CAISO independently identifies the transmission development needs in its transmission planning process, including the energy efficiency and distributed generation assumptions provided directly by the CPUC.

Additionally, we found that Texas and New York have pathways for expediting transmission projects. In Texas, a project designated by the state PUC as “critical for reliability” may receive expedited permitting that halves the deadline for decision-making on an application from 12 months to 6 months. In New York, a project that is found not to have adverse environmental impacts or that is planned for an existing right-of-way may receive expedited permitting that shortens the statutory review period to 9 months from the typical 12 to 18 months. No such expedited permitting pathways exist for granting a CPCN in California, despite CPUC leading CEQA and CPCN permitting reviews for transmission lines.

Where do we go from here?

The current transmission development process in California is marked by delays. The state has the longest statutory timeline of all western states for approving a CPCN, there are no avenues for expediting CPCN permitting, and the “no-project alternative” analysis required by the CPCN review process duplicates CPUC inputs in CAISO’s transmission planning process and is in addition to environmental reviews under CEQA.

Importantly, there are two efforts underway to address at least some of these challenges. Between them, SB 619 (Padilla) and SB 420 (Becker) would consolidate transmission permitting authority at a single state agency as well as eliminate unnecessary redundancies in the permitting process.

No matter the outcome of these proposals, it is clear that California’s climate policy leadership is not currently matched by its clean energy infrastructure deployment leadership.